By Aaron Foyer

VP, Orennia

Aside from elite Call of Duty virtuosos, chipmaker Nvidia hasn’t exactly been a household name. For decades, the company was known for making gaming chips. It was discovered later that its chips were ideal for running specialized artificial intelligence software. With the public’s recent awakening to AI’s potential, demand for Nvidia’s hardware soared, along with its market value. But Nvidia’s recent share price run and the spike in demand for its specialized microchips are just part of a broader story about power markets that may upend decarbonization targets: the growth of AI and the colossal energy needs of data centers.

Ironically, it may be the large tech companies, some of the largest signatories of American PPAs and firms that have made climate pledges core to their identities, whose data centers limit the potential for future electrification efforts.

Background: Founded in 1993, Nvidia found its niche when it developed the graphics processing unit (GPU) in the late 90s. These specialized chips were crafted for meeting the intense graphics needs of the emerging gaming industry.

Nvidia eventually realized the parallel processing design of GPUs made them ideal for running AI-related tasks. Through investing in new technologies and software, Nvidia created a strategic moat of complexity around its business. By many estimates, the company had a global GPU market share of roughly 80% by the 2020s, just in time for the arrival of large language models – a form of generative AI.

Enter ChatGPT

Following the November 2022 public release of OpenAI’s chatbot, a wave of entrepreneurs took to developing a suite of new technologies and software using AI and large language models. From accelerated computer programing to overcoming writer’s block, there was suddenly a new category of applications that required Nvidia’s specialized chips. And behind the rush of new use cases for the technology came its growing energy needs.

Why? AI is power hungry. Apart from regular daily use of the software, each model consumes huge amounts of electricity during its training well before the product ever hits the market.

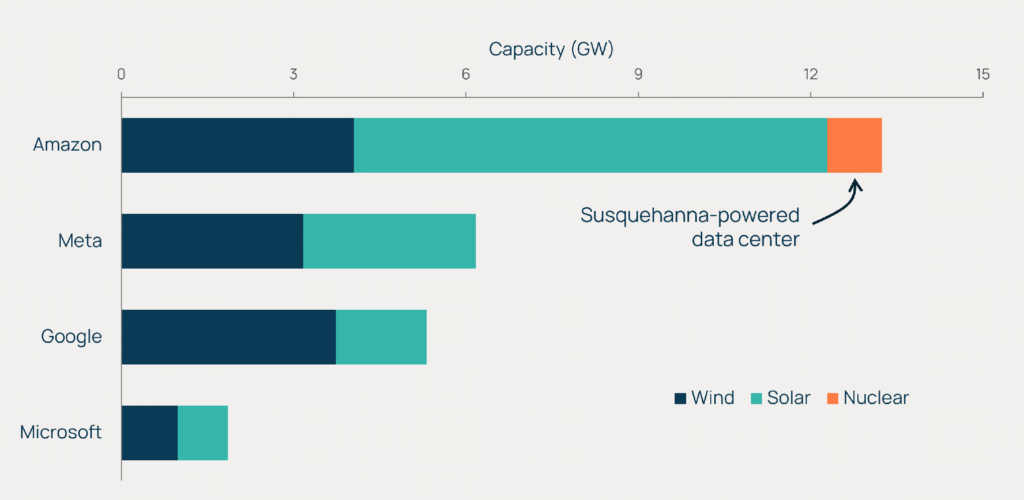

Many of the largest data center users, including Amazon, Meta, Google, and Microsoft, have been actively signing renewable power purchase agreements (PPAs) to achieve corporate climate pledges. Collectively, the four have signed over 25 GW of publicly released PPAs in the US alone. In early March, Amazon bought a 960-megawatt data center powered by the adjacent Susquehanna nuclear generating station under a 10-year PPA.

US Power Purchase Agreements by Big Tech

Note: Numbers reflect publicly released data

Source: Orennia Ion, Electrek

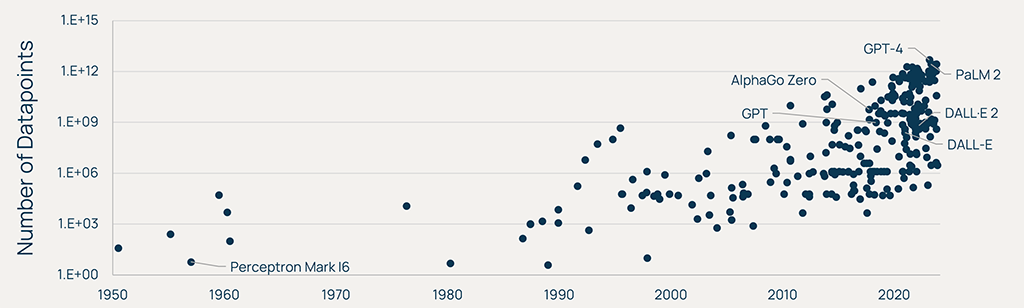

Deep dive: Training AI models now involves analyzing trillions of datapoints to make data links, like neurons creating connections in a human brain. The amount of datapoints fed into each model has grown exponentially over time.

According to statistics from Epoch, a non-profit that gathers key historical AI data, the average model published in 2023 had a training dataset comprised of more than 550 billion datapoints. ChatGPT-4 used 4.9 trillion. Contrast this with an average of 81 billion datapoints used for 2020 models and just two billion for those published a decade earlier in 2010.

Datapoints Used for Training Different AI Models

Source: Epoch

On energy: The training and use of AI models has created a shift in energy demand that has yet to dawn on many. In an interview at the World Economic Forum earlier this year, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman spoke about AI’s enormous energy requirements.

“We still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology. There’s no way to get there without a breakthrough. We need [nuclear] fusion or we need radically cheaper solar plus storage or something at a massive scale.”

-Sam Altman, OpenAI CEO

On top of the additional electricity needed to feed the models, there are questions about where all that data will be run through, and which grids can support the new data infrastructure.

Insufficient power supply?

With the recent spike in energy requirements for data centers, there are new concerns about utilities being able to provide enough electricity for future sites. In the latest forecast from PJM, Dominion Energy – the utility that services a key Virginian data center hub – sees its load growing between 5% and 5.5% annually from now until the late 2030s, more than doubling current demand. Much of that growth is coming from data centers, a sector whose electricity demand Dominion projects will increase 376% between 2023 and 2038.

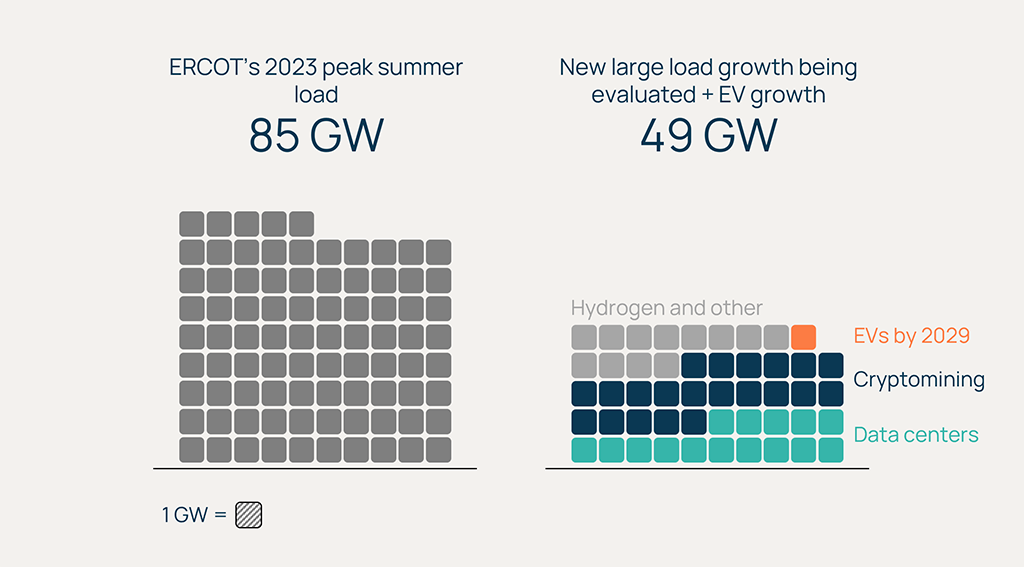

In early 2023, a report from Texas’s ERCOT showed 48 GW of reported additional large load being evaluated, most of it data centers and cryptomining, with 39.2 GW hoping to come online by 2027. Add to that 1.1 GW of additional load expected from EVs in the state by 2029 and you have nearly 50 GW of potential new load by the end of the decade.

ERCOT Large Load Being Studied vs. 2023 Peak Summer Load

Source: ERCOT

Considering the Texas interconnection’s peak summer load was 85 GW last year, adding just the 12 GWs from data centers would increase ERCOT’s peak load by 15%. That would jump to 42% if it included cryptomining projects, themselves essentially data centers. Some of the new load may be flexible, but the scale of the growth from data centers is nonetheless remarkable.

Back to coal? There are concerns about the demand growth for electricity outpacing the building out of clean electricity, leading a reversion to higher-emitting sources.

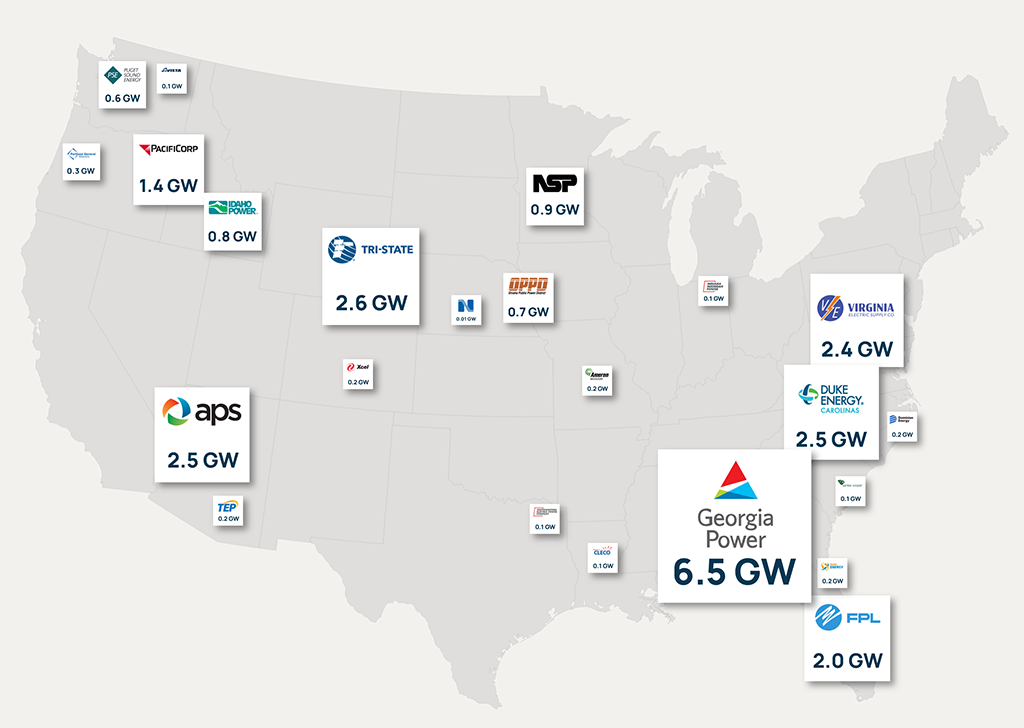

Georgia’s largest utility, Georgia Power, is asking regulators to approve new and renew 3.4 GW of generation to support new demand in the region. According to the utility’s testimony, 80% of that generation will be used for new data centers (read the full Neuron report from Orennia here). Of the new or renewed capacity requested by Georgia Power, 70% is either natural gas or coal, generated locally or imported from neighboring states.

Utility Net Summer Peak Load Growth* from 2024 to 2030

*From utility integrated resource plans released 2023 or after

Source: Orennia Ion

Demand for data centers is growing

Selecting a site for a data center is no arbitrary task. There are several key considerations, with price and availability of power being among the most important.

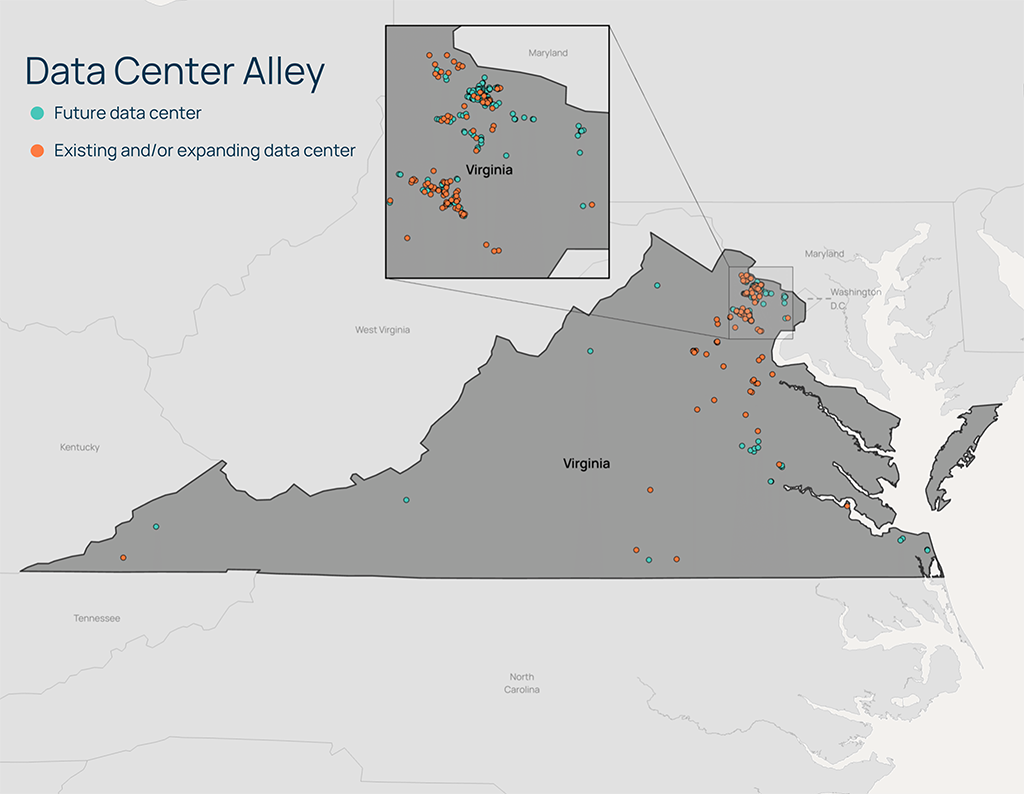

In the US, there are a several key regions that host data centers at scale, including Silicon Valley and Texas. The most important by far is in northern Virgina. Often referred to as Data Center Alley, the largest hub of data processing in the world exists just a stone’s throw from Washington. It’s so large, an estimated 70% of the world’s internet traffic travels through this key American tech hub every day.

Located initially for its proximity to where the internet was invented at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (APRA), the region also benefits from cheap electricity and plenty of municipal water, which is tapped to cool the machines.

The AI revolution and its sudden increased demand for data centers may consume clean electricity that was previously intended to decarbonize other industries.

Future and Existing Data Centers in Virginia

Source: Piedmont Environmental Council

Could data centers derail electrification efforts?

There is no doubt that AI has defense applications. Whether it’s accelerating the development of new defense software, gathering intelligence or orchestrating drone swarms, AI may be the deciding factor on future battlefields. With such stakes on the line, governments may increasingly view the development of AI products and their associated data centers as a matter of national security, prioritizing their development over other initiatives.

Should the demand for electricity for AI be as large as Sam Altman insinuated to the crowd at Davos, then lower priority sources of new demand could be dropped. The planned electrification of heating, transportation, and heavy industry may be pushed out if there simply isn’t enough electricity supply, being used instead to power data centers.

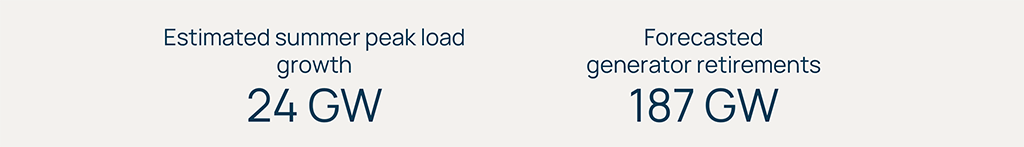

Zoom out: The sudden emergence of new demand from data centers is striking. In PJM’s January 2024 Load Forecast Report which compares load estimates from both this year and last, significant load growth is expected for every power zone. This contrasts to the same forecasts last year, where most zones showed either flat or falling future loads. A significant course change in just one year.

The true impact of AI, data centers and Nvidia’s specialized GPUs are yet to be fully understood. AI could help unlock supply-demand efficiencies and enable new energy transition technologies. Several startups are looking to vastly improve the energy efficiency of GPU processing chips. But it could still be that the energy consumption and strategic importance are underestimated.

Summary Sparks

Long electricity and grid resilience? After decades of low growth, the emergence of new tech sectors and broader electrification goals are increasing the demand for electricity. This comes just as some thermal assets are scheduled to retire. Investments in transmission, distribution, storage, smart grids, microgrids and demand-side management would likely benefit from this trend.

Harder to site new data centers? Picking locations to build data centers will become harder. Understanding interconnection queues, future electricity prices and nodal carbon emissions intensities will be key to making strategic decisions for developers. This is true for data centers and all energy-intensive infrastructure.

Electrification challenged? The demand for electricity from data centers may begin competing with other new sources of power demand. This includes electric vehicles, heat pumps, electrolysis-based hydrogen, and industrial needs. It’s yet to be determined where data centers might sit in terms of national priorities, but their growth may hinder electrification and other decarbonization efforts.

Aaron Foyer is Vice President, Research and Analytics at Orennia. Prior to Orennia, he leveraged his technical background in management consulting and finance roles. He has experience across the energy landscape including clean hydrogen, renewables, biofuels, oil and gas, petrochemicals and carbon capture.