Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Options seem limited as the airline industry looks to cut emissions

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

If you’re a fan of travel history, you know the Golden Age of Flying was in the 1950s and ’60s. In a time before humans were packed like sardines into planes, flying was for the rich and glamourous.

Amenities were key: Areas with white linens, piano lounges and ice statues served as social gathering spots for patrons who, due to the cost of tickets, were all wealthy. Pilots were rock stars. Flight attendants, dressed in haute couture uniforms, served as the in-flight entertainment, often putting on fashion shows in the aisles. Bartenders poured crisp Tom Collins made using Gordon’s Dry Gin as five-course meals were prepared. It was an era Jerry Seinfeld would have struggled to write airplane food jokes about. (What’s the deal with beluga caviar?)

It was the Boeing 747 that finally brought the Golden Age of Flying to an end. Decades of spending by wealthy travelers funded the development of jumbo jets – large-bodied aircraft that democratized flying, making it affordable for the broader public. Open your MBA textbooks and it’s a classic example of price skimming – using higher initial prices to help lower product costs over time.

Cocktail hour on Lufthansa’s first-class ‘Senator’ service in 1958 // Airline: Style at 30,000 Feet/Keith Lovegrove

Today, airlines face a new challenge. As the industry looks to cut emissions, its options seem limited and expensive. To make matters worse, it’s a highly competitive industry with both razor thin profit margins and price-sensitive customers. So how should industry fund costly emissions-cutting technologies when most travelers won’t budge on price?

The answer: Price skimming by segment. Focus on specific flyers with large budgets and mandates to cut their flight emissions. Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are emerging as the potential solution for airline emissions but remain expensive. Bankers and consultants might be the early adopters of SAF, bringing costs down for the rest of us.

As far as emitting industries go, aviation is small but meaningful. The sector accounted for 2% of energy-related emissions in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency.

Emissions from aviation are notoriously challenging to address. The Electrify Everything movement can’t really apply to aviation, as lithium-ion batteries have such low energy densities that fully-electric flights barely muster short-haul flights without a good tail wind. For long-haul, transatlantic flights, you still need a dense combustible energy source like jet fuel to make it work.

Enter SAF: Sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are liquid fuels that have the high energy density of jet fuel but are made in ways that ultimately reduce emissions.

Key types of SAF:

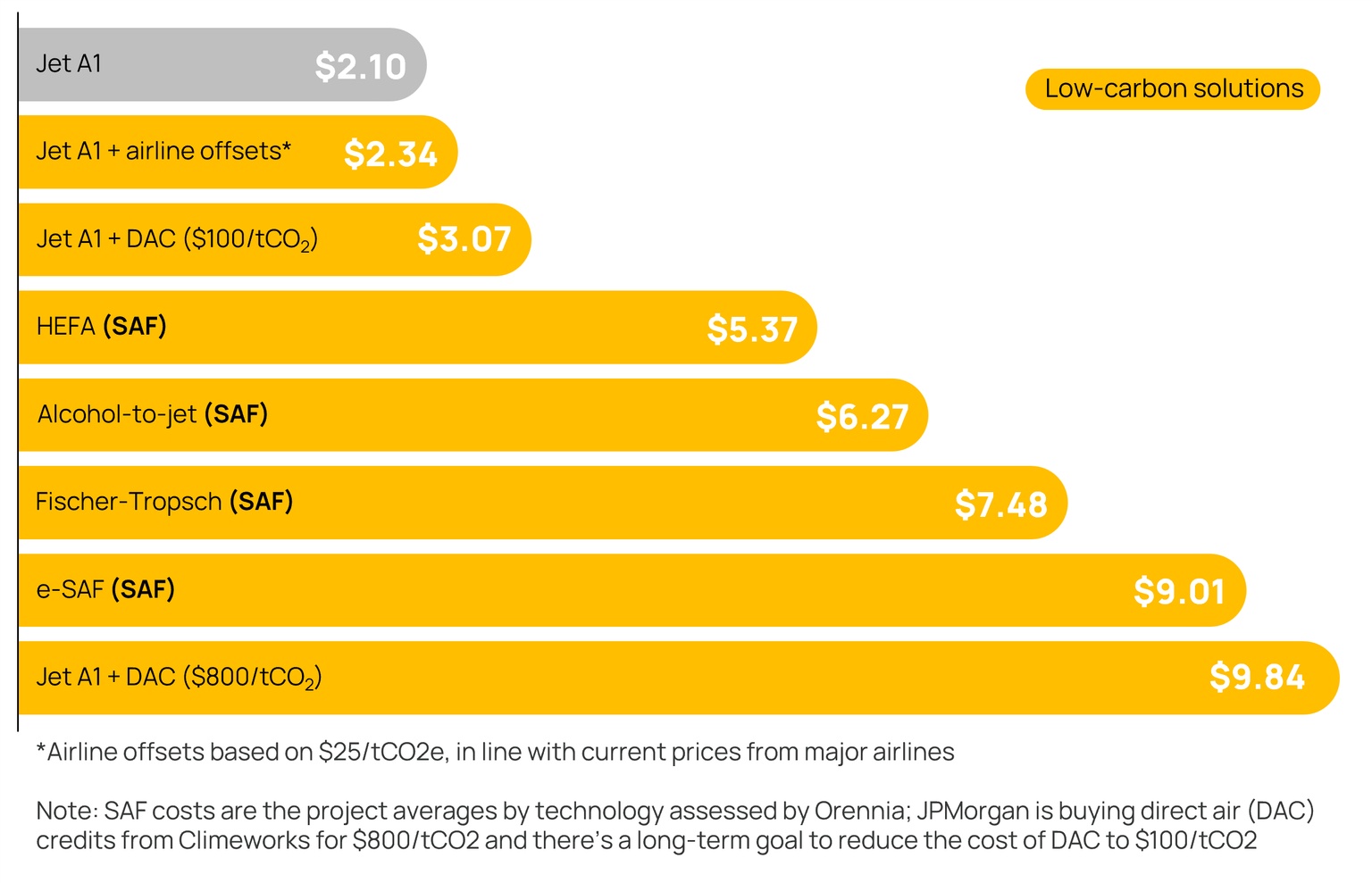

Depending on the pathway, SAF can partially or fully eliminate emissions from airlines. There are several obstacles facing the industry, including the availability of feedstock. But its main challenge is cost. Low-carbon aviation fuels are expensive.

Source: Orennia, United Airlines

While many of the processes needed to make these sustainable fuels have been around for decades – Fischer-Tropsch was developed in 1925 – they are only just starting to be utilized at scale. Orennia tracks SAF projects across North America, and our database has just one SAF project that was online prior to 2023.

Technology-wise, of the 16 SAF projects operating around the world today, 15 of them are HEFA, likely due to its lower production cost. Despite being the cheapest, HEFA is still 2.5 times the price of traditional Jet A1 jet fuel. Being a biofuel, HEFA faces a natural cap on its growth and the general view is its production cost is unlikely to drop significantly in the future.

How much would ticket prices increase today by using SAF instead of jet fuel?

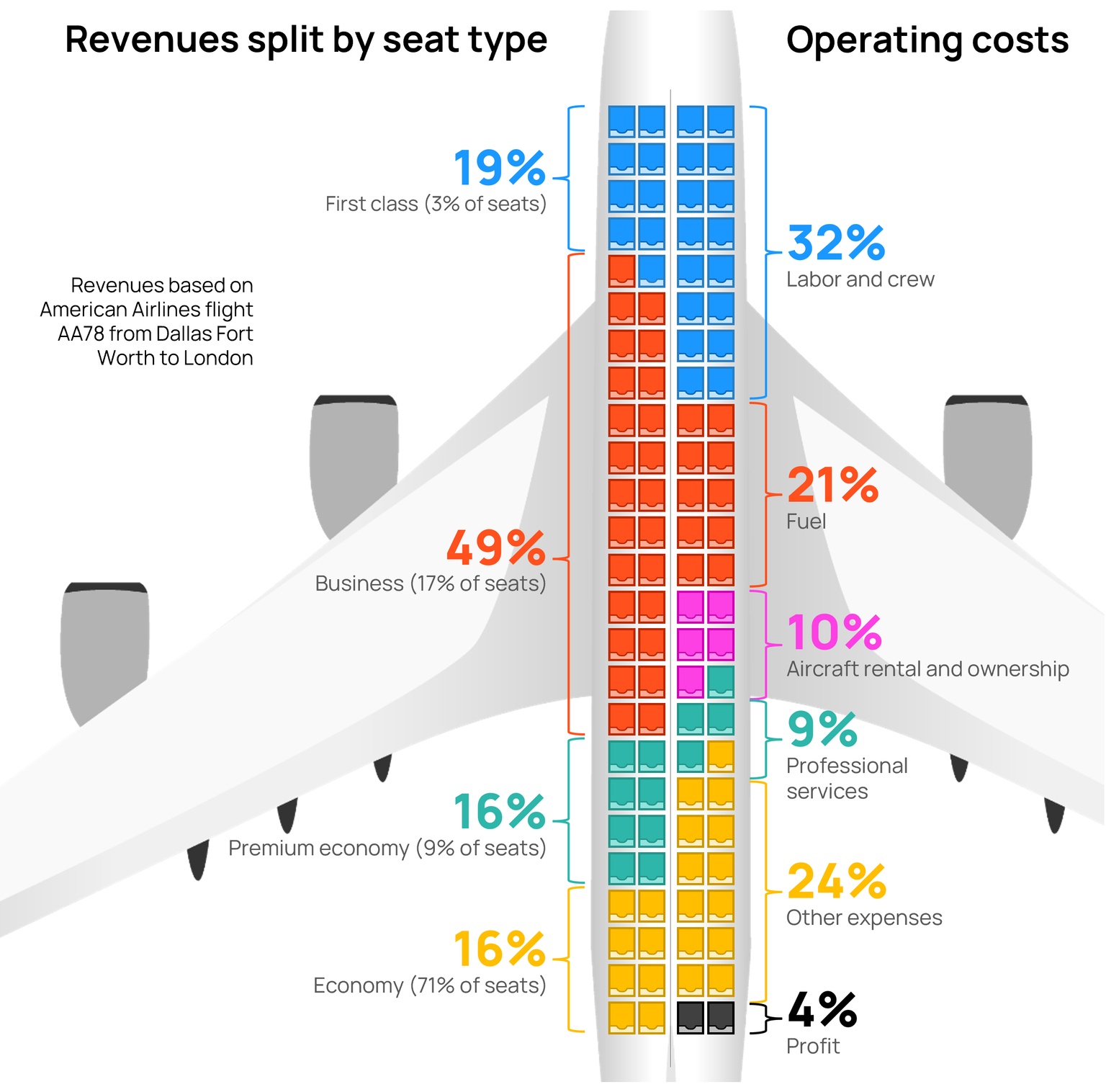

Substitution: Airlines for America recently broke down the operating costs of US passenger flights and found fuel accounted for one-fifth of total costs. So, blending in just 10% of a more sustainable fuel that was three times the price of traditional jet fuel would increase flight costs by ~4.5%. A full substitution for HEFA fuel would increase flight prices by more than 30%.

Even without trying to address emissions, the economics of air travel are challenging. As Virgin Airlines founder Sir Richard Branson put it, “if you want to be a millionaire, start with a billion dollars and launch a new airline.”

In their best years, airline profitability lags other industries. US airlines had a pre-tax profit margin of just 4.6% in 2023, trailing the American industry average of 17.4%. And there’s hesitation among airlines to start raising fares.

Fare-conscious: The prospect of raising ticket rates to help fund green initiatives is tough in a competitive industry where customers are sensitive to flight prices.

In a recent survey published by Airlines for America, the trade association found ticket price was the single most important factor influencing why a flight was chosen by consumers – 53% of respondents selected it as their top motivator. Nearly half of flyers are unwilling to pay anything to improve the sustainability of their flights. Less than 20% would pay $20 or more. This is all the more surprising given respondents believed air travel is more emissions-intensive than it really is.

In short, flyers think it’s bad but are unwilling to pay to make it better.

The 24-year-old sitting in business class working furiously on some slides.

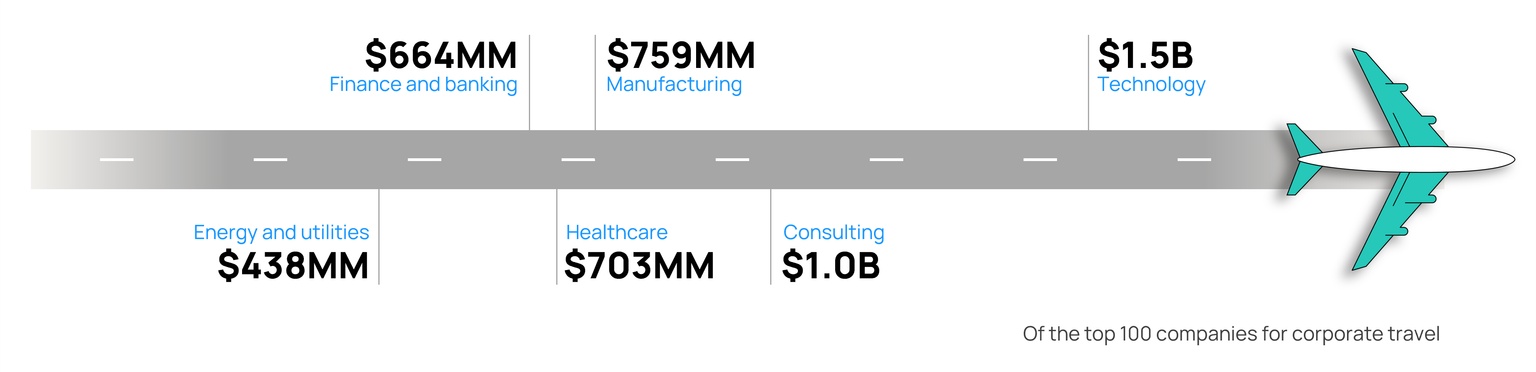

Consultants, bankers and tech workers are currently some of the largest buyers of SAF in the US. Analyzing the top 100 corporate air travelers in the US, Business Travel News found the three industries together spent more than $3 billion on US-booked air travel in 2022.

Source: Orennia, Business Travel News

Why it matters: Especially for banking and consulting, emissions related to travel account for a significant share of company emissions. In McKinsey’s 2023 ESG Report, the consulting firm reported that nearly half (!) of its 580,000 tonnes of carbon emissions for the year came from air and ground transportation.

With air travel accounting for such a large share of corporate emissions, usually paired with high profit margins and ambitious climate targets, these firms are both motivated and able to pay a premium for low-carbon aviation fuel.

Economies of scale: If there’s anything a bunch of consultants and bankers know well, it’s the advantage of size. In April 2021, several major companies founded the Sustainable Aviation Buyers Alliance (SABA). Made up of names like Amazon, BCG, McKinsey, Google, JPMorgan Chase & Co and Morgan Stanley, SABA is working to drive the global adoption of SAF. At the end of last year, the collective announced the purchase of 850,000 gallons of SAF to be used by JetBlue.

While the SAF industry is still looking to take off, airlines are using other means to help reduce travel emissions for their customers.

Along with its participation in SABA, BCG has been working separately with Climeworks to remove carbon dioxide directly from the air. The 15-year agreement with the direct air capture firm will remove an estimated 80,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The price was undisclosed, but Climeworks signed a similar deal last year with JPMorgan at a cost of $800 per ton of carbon dioxide.

While there looks to be limited scope for cost reductions in HEFA, direct air capture could be a technology set up for meaningful cost reductions. Fuel costs would increase just ~30% if capture cost could reach $100 per metric ton, a long-term goal, presenting another option for airlines.

More controversially: Airlines currently lean heavily on carbon offsets to make flights more sustainable. If you go to buy a ticket today, among the gauntlet of annoying add-ons to work through to finalize the purchase, most airlines offer an option to offset the emissions from your flight. These are done almost exclusively with carbon offsets at ~$25 per metric ton of carbon dioxide.

We spent time digging through the disclosures of several global airlines and found most offsets are coming from either nature-based or clean cooking projects. Experts have cast doubt on the quality and validity of both. This is due to both challenges in determining true emissions reductions and instances of outright fraudulent projects. While there are unquestionably high-quality offset projects out there, it’s hard right now to tell the roses from the thorns, which could spell trouble for airlines.

Customers have yet to be convinced to spend extra to make air travel greener. According to the poll by Airlines for America, just 3% of travelers purchased either carbon offsets or bought a SAF fund credit for a flight last year. And while SAF facilities are growing, it’s still early days. For operating SAF facilities in the US, there are only three.

There are some positive signs. On a recent Catalyst podcast with Delta’s chief sustainability officer, it was suggested that demand for SAF from corporate flyers, including consultants and bankers, far outstrips supply. SAF projects likely have some willing buyers.

Bottom line: Consultants often prescribe more consulting as the cure. For SAF to take off, they might just be right.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.