Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

There’s a global gas turbine shortage

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Jet power is often thought of as a product of the Cold War, with jet bombers being some of the most iconic symbols of the period. While famous jets were flown by the US and USSR after World War II, including the American B-47 Stratojet and the Soviet Tupolev Tu-16, neither country had a jet-powered plane that saw combat during the conflict.

But the Germans did.

The first jet: Developed in secret, the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter saw its first combat with the German Luftwaffe in 1944 where it absolutely stunned adversaries. The Me 262 could travel more than 100 miles per hour faster than famous Allied counter-fighters like the American Mustang or British Spitfire, on top of having better acceleration and greater firepower.

Recognizing they couldn’t win in a fair fight in the air, American and British pilots took to attacking the German jets during takeoff, when they were the most vulnerable.

Following the war, the Allied countries scoured Germany for talented scientists and engineers to bring back home and develop their own technologies and industries, like jet planes and rocketry. In the US, this international brainlift was known as Operation Paperclip.

A Messerschmitt Me 262 plane at the Evergreen Aviation Museum // Wikipedia Commons

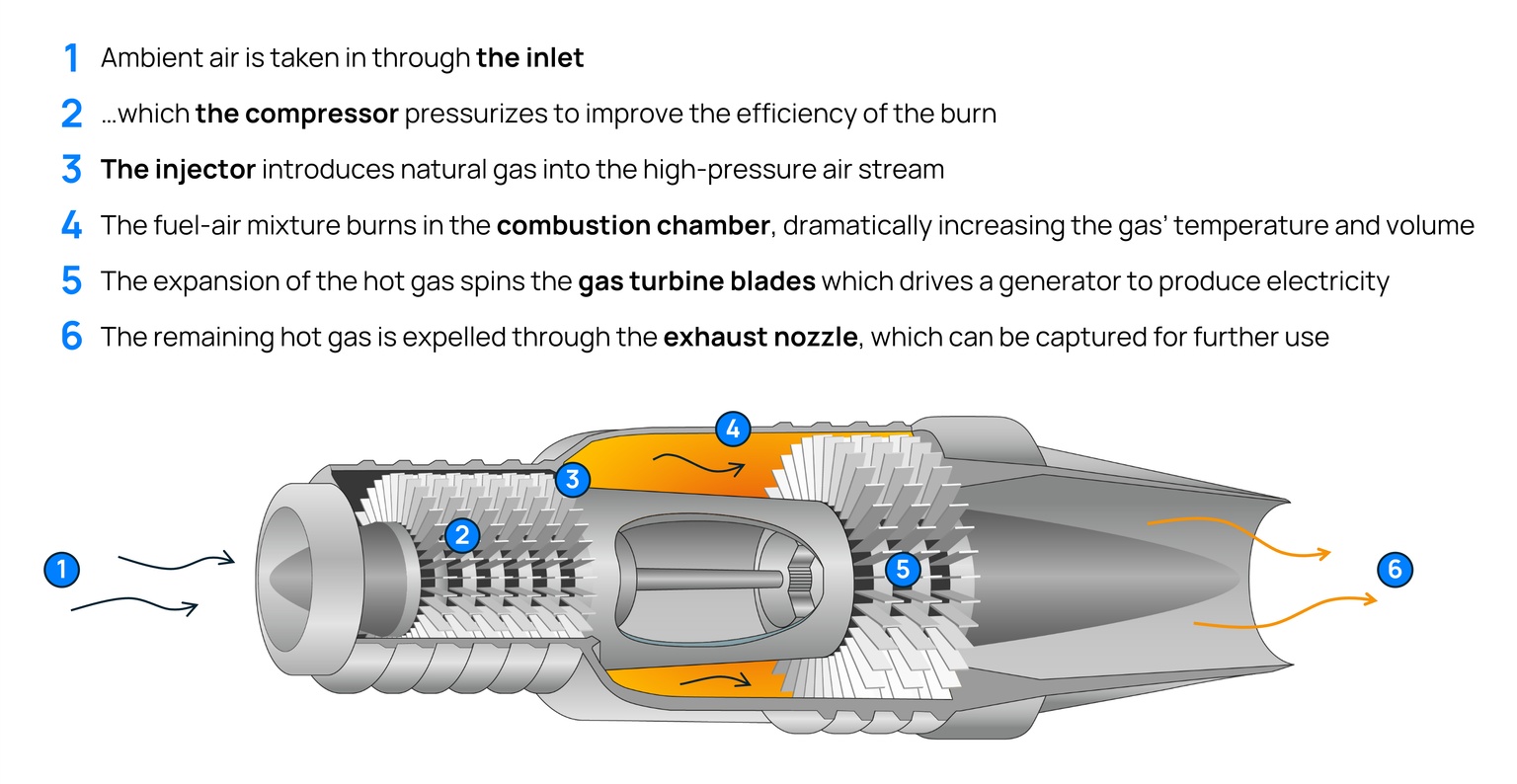

One of the German engineers brought over to the US by Operation Paperclip was Hans von Ohain, credited as being the designer of the world’s first gas turbine to power an aircraft. His work helped literally and figuratively launch the Me 262.

Lasting legacy: More importantly, his work in the compression and expansion of hot gases in jet engines helped pave the way for modern gas turbines. Functionally similar to early jet engines, turbines now lie at the heart of today’s most advanced gas plants. And no small feat: gas plants produced more power than all other technologies combined in the US last year.

Now, like the Cold War arms race, geopolitical rivals are competing to develop the latest technological innovation — artificial intelligence. Power for data centers has emerged as one of the key bottlenecks in the race for AI, with companies scouring North America for the fastest available connections to reliable power. This has led to a renaissance for gas power, with companies looking to build new gas plants at a rate not seen in decades.

One teeny, little problem: There’s a global gas turbine shortage. Global manufacturers can’t keep up with orders, downpayments are hurting the economics of new plants, and prices for new gas plants have been going up for years. Yet, to keep up with the likes of China, North America needs power fast.

So, will gas power be the AI savior many are hoping it will be or will these hurdles turn out to be too large to overcome?

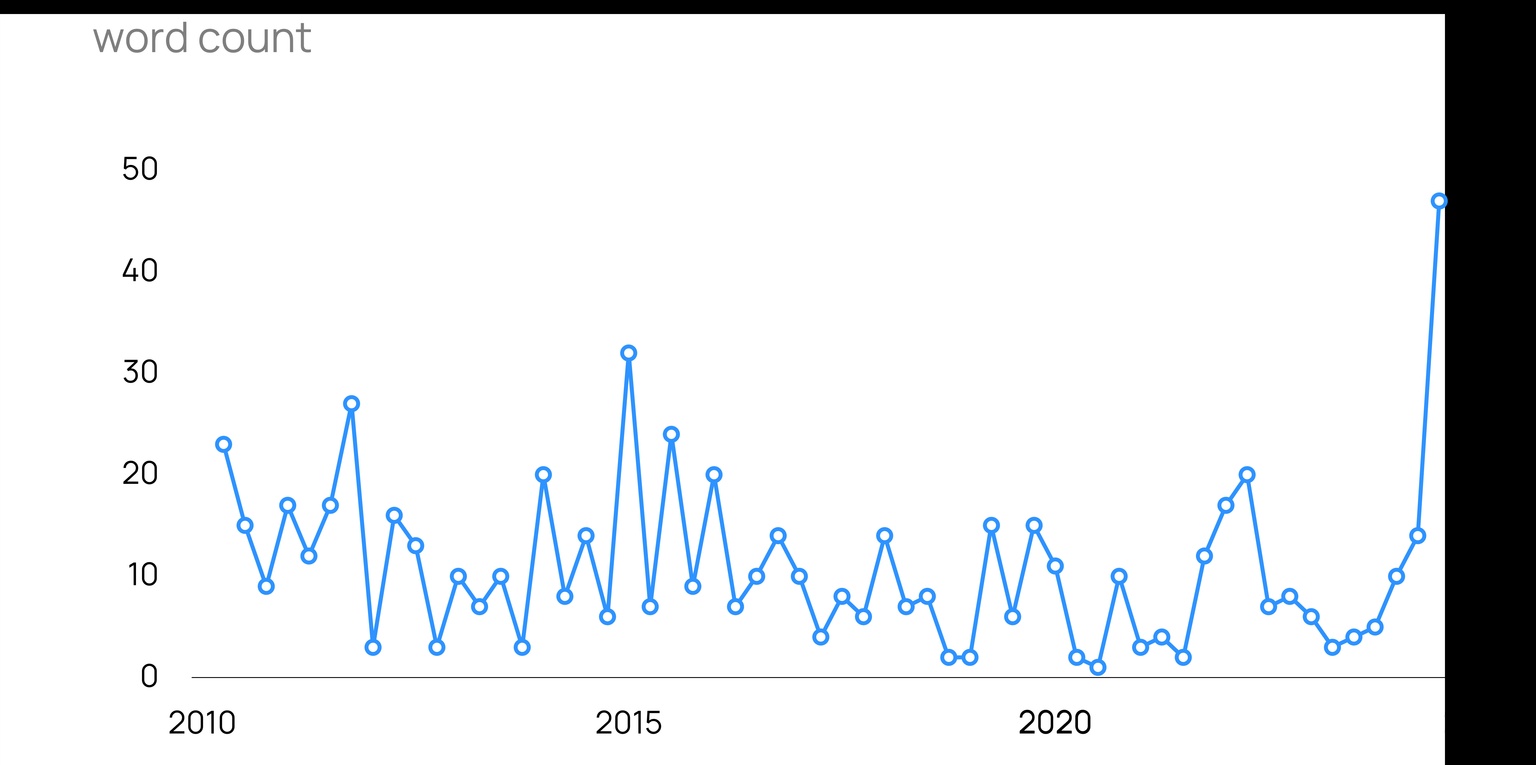

Being the largest US utility by market cap, NextEra is often seen as a bellwether in the US power sector, particularly clean power. So, it’s telling that during the company’s latest investor’s call, gas was brought up more than at any point in the past. In fact, despite operating 22 times more wind, solar and battery capacity across North America, gas was mentioned more than all three technologies combined on the call.

NextEra quarterly earnings calls // rioc.ai

NextEra is not alone facing the wave of new gas demand. The amount of gas projects that entered the US interconnection queue for approval to connect to the grid tripled from 2023 to 2024.

It’s no surprise why: Electricity has become one of the key bottlenecks in being able to develop new data centers, with BCG listing access to power as one of the most significant barriers to their growth. And for AI workloads, data centers require near round-the-clock baseload power. With coal sunsetting and new nuclear still beyond the horizon, gas power seems the obvious choice.

It should also be obvious that you can’t exactly DoorDash a new gas plant.

Consider this: The H-Class high-efficiency turbine manufactured by Siemens in Germany is made up of more than 7,000 individual parts. The 11-meter-long machine weighs more than a fully loaded Airbus A380 and is designed to withstand temperatures up to 1,500 degrees Celsius as its blades rotate at more than 1,700 kilometers per hour. Some parts of the blades exceed the speed of sound as they turn, with the distance between them no greater than the thickness of a postcard.

A modern gas turbine is a wonder of engineering.

Due to their complexity, there are just a handful of companies around the world that can even conceive of making one. The big three are Siemens Energy (Germany), General Electric (US) and Mitsubishi (Japan), together accounting for two-thirds of turbines for gas-fired power plants under construction around the world today.

And unfortunately for those who checked “ASAP” on their gas plant delivery date, there’s a five-year wait for new orders.

Backlog: On Siemens’ quarterly earnings call in February, when pressed for the earliest delivery date for new units, CEO Christian Bruch said “[2029], 2030 and then onwards.”

The CEO of GE Vernova, Scott Strazik, gave a similar answer in January. “The intensity of discussions for… premium slots in the out years going, and I'm talking premium slots 2028, 2029 really,” he Strazik said.

Turbine capacity under construction by company headquarters // Global Energy Monitor

The orders just keep coming in.

Siemens Energy has seen its pipeline of turbine orders expand in recent years. In 2020, the German firm’s Gas Services business that makes the power units had a backlog of €79 billion. In the few years since, that jumped to over €123 billion.

Yet, even with orders piling up, manufacturers are maintaining some capital discipline in investing in the expansion of their factories, despite the Trump administration’s tariffs to drive domestic manufacturing growth. It’s been less than a decade since GE shares shed nearly 70% of their value as a result of the company betting too aggressively on gas, a mistake it’s not keen to repeat.

With a multi-year backlog, top manufacturers are reportedly going full Jerry Maguire and requiring buyers to show them the money upfront with large deposits on new turbines orders.

Big industrial turbines often go for hundreds of millions of dollars, so it gets hard to make the numbers work on a project if companies have to put down even half that cost on equipment they won’t get to use for five years.

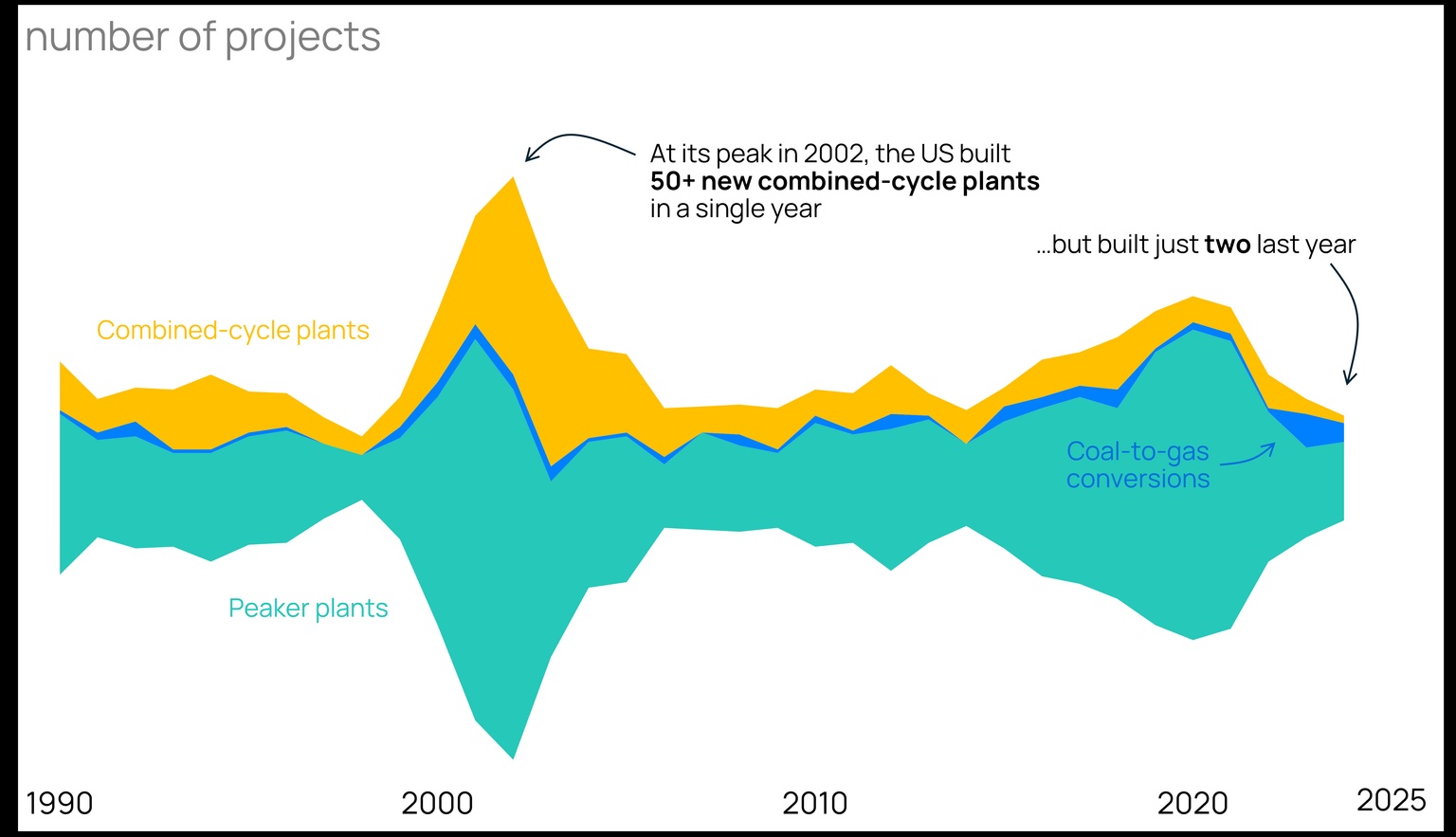

Shaking the rust off: Beyond just the turbine, other project costs have been climbing with the gas plant construction industry not the well-oiled machine it once was. The early 2000s were the heyday of building large plants with combined-cycle gas turbines, with the US building upwards of 50 large plants per year. The country built just two last year.

And without iteration, there is cost inflation. This was seen with the two Vogtle nuclear reactors brought online in 2023 and 2024, whose costs more than doubled as the industry re-discovered how to build nuclear plants.

As NextEra CEO John Ketchum recently told investors, “This is an industry that really hasn’t seen any active development or construction in years … all of that puts pressure on cost.”

Source: Orennia

To put some numbers behind that, NextEra’s latest investor deck highlights that the capital cost of new combined-cycle gas plants are expected to triple from 2021 to 2030, the latter being projects that are ordered today.

Pair that with the 50% down payment now required for plus the time value of money, and the cost of new large gas projects has essentially quadrupled in just four years. Eggs have nothing on gas plants.

This is best exemplified by Engie, which withdrew two major gas peaking projects in Texas in February, citing equipment delays and higher costs.

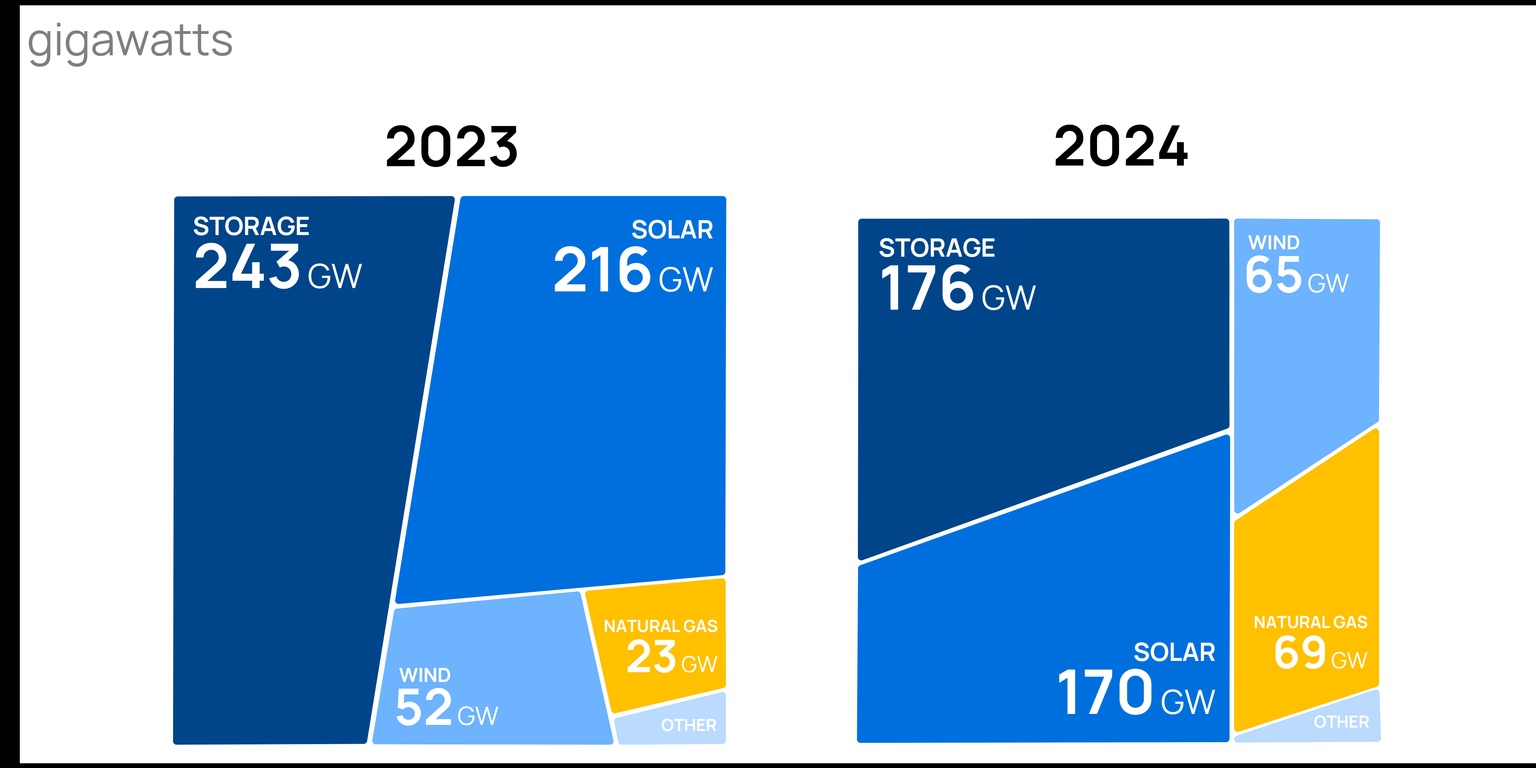

For the data center developers and others looking for a quick fix to their large new power needs, gas is unlikely to be a meaningful solution until at least the 2030s. While gas projects are increasingly requesting access to the grid, renewables and batteries still dominate the interconnection queue.

Source: Orennia

And for now, with elevated capital costs, renewables and batteries are cheaper, too. NextEra pegs the cost of a new combined-cycle gas plant today at nearly double either wind or solar paired storage capabilities.

The German Me 262 jet fighter was a revolution in aerial combat, but it didn’t turn the tides in the conflict.

Just as the Siemens of the world can’t fully meet today’s turbine demand, the Germans struggled to ramp up production of the Me 262, in part because of just how complicated turbine engines are. From struggles acquiring then-exotic metals like nickel and cobalt to supply chain constraints, producing reliable jets at scale was never in the cards. The Me 262 was a game-changer stuck in a logjam.

Bottom line: In today’s grid, the buyers who waited may also find that game-changers don’t come cheap — or soon.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.