Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

The challenge of filling energy jobs in North America

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Franklin Delano Roosevelt stepped into the Oval Office in 1933 at a time when the US needed true leadership from its president. In the depths of the Great Depression, unemployment sat at more than 20%, and even those with jobs faced low pay or part-time work. Shanty towns popped up and were given the nickname Hoovervilles, a shot at former president Herbert Hoover, whom many blamed for the downturn.

Like priming the pump on an old Model T, FDR introduced his historic New Deal, a program to, in part, create jobs, often for the sole purpose to get Americans moving again.

“Our greatest primary task is to put people to work. This is no unsolvable problem if we face it wisely and courageously. It can be accomplished in part by direct recruiting by the Government itself, treating the task as we would treat the emergency of a war,” Roosevelt said in his inaugural address in March 1933.

TVA: A few months later, the 32nd president signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act, part of the historic jobs push in the New Deal. The Act was written to address flooding issues, replant forests and, most importantly, electrify the poor states that span the Tennessee River Valley.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federal corporation, was created out of the Act and more than 9,000 people found employment with the TVA within a year, building, among other things, 16 hydroelectric dams. This helped electrify farms, which in turn helped farmers churn out more food and boost profitability for landowners.

Early Tennessee Valley Authority workers // Rawpixel

Nearly a century on, TVA is now one of the largest power producers in North America. Boasting nearly 30 dams, dozens of coal- and gas-fired power generators plus three nuclear plants to serve six states, the government-enacted corporation is now the largest public power utility in the US.

Fast forward: TVA and other major power producers face new challenges today. The rapid rise of power demand, particularly from data centers, are challenging even seasoned companies that have been building projects since the Great Depression. But unlike the 1930s, when there was a surplus of workers eager to find gainful employment, there is a shortage of talent today, especially young talent, with the skills necessary to carry out our current electrification push. Power-line installation just doesn’t have the ASMR chops needed to attract the TikTok crowd.

Without the requisite talent, projects will face delays, inflation or cancellations. So, what are we to do about it?

Let’s first acknowledge this is not a global problem, but a local problem. All else equal, more jobs is a good thing for the world.

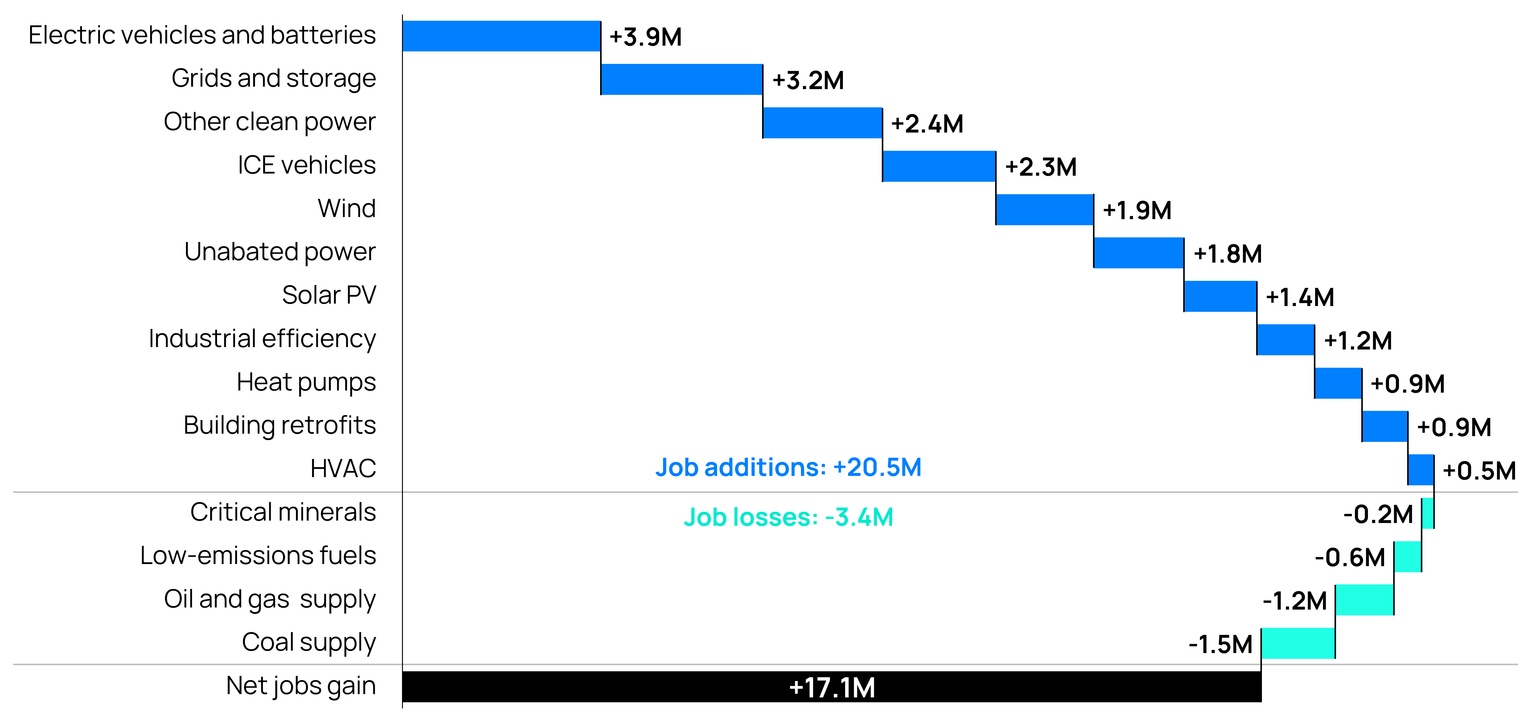

Employment charge: Between 2019 and 2022, jobs in the global energy sector grew by 3.5 million people, with more than half of those coming from five sectors: solar, wind, electric vehicles and batteries, heat pumps, and critical mineral mining. By the end of the decade, there could be another 20 million new jobs across the various energy sectors, more than offsetting losses from the expected shift away from or slowdown in fossil fuels.

But in North America, filling these new roles will be a challenge.

Source: International Energy Agency, World Energy Employment 2024

In Canada, roles in the renewable sector seem harder to fill than most. In a report published earlier this year, Electricity Human Resources Canada found that more than 13% of renewable energy jobs were unfilled in 2023, much higher than those in other trades, which is closer to 2%.

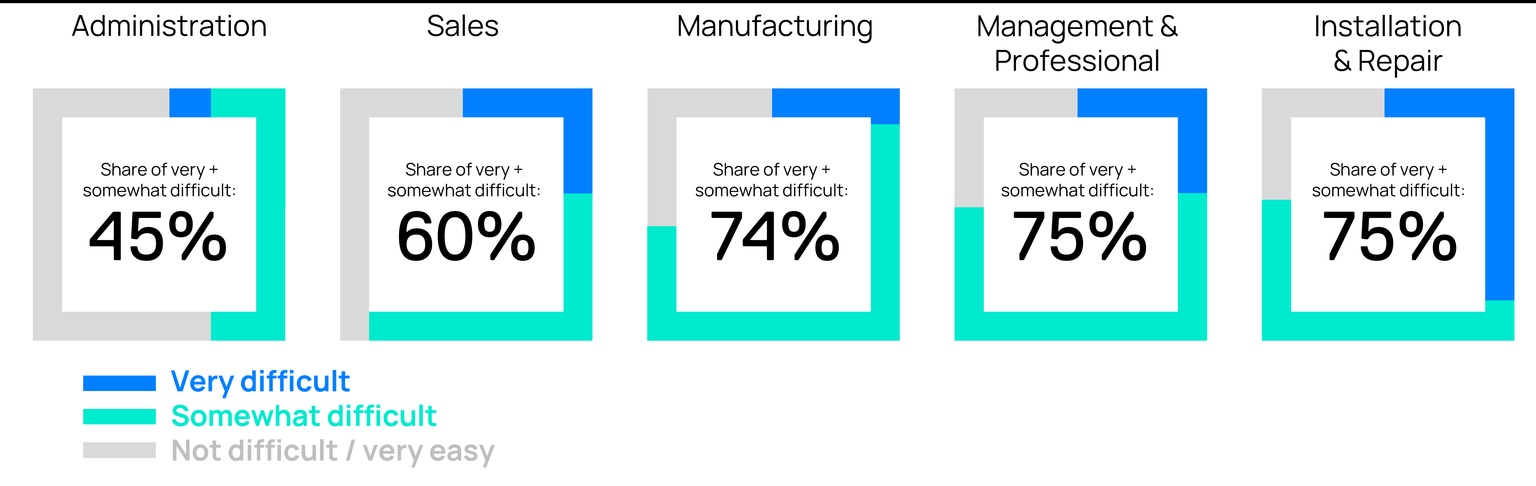

Globally, the workforce agency Manpower found 76% of employers in energy and utilities are struggling to find the skilled talent they need, while the Center for Automotive Research found 82% of professionals working in the electric vehicle and battery space reported a shortage of skilled local applicants, with the largest gaps in the upstream supply chain of batteries — mining and refining — plus cell manufacturing and pack assembly.

These are likely to be made more challenging with growth in clean energy.

Consider this:

Eventually, a country just runs out of the people necessary to build what needs to be built.

Source: International Energy Agency, World Energy Employment 2024

Of all the critical jobs up and down the power sector’s supply chain, there are a few that are likely to cause the greatest headaches:

Miners: Before powerlines can be strung and batteries built, a range of metals and minerals must be extracted from the Earth. Demand for critical minerals grew 50% between 2010 and 2021 and is expected to continue to grow into the foreseeable future. One of the very first presidential actions of the new administration was to pass measures to increase American mineral production. It’s not clear who will be doing the actual work.

Despite being a lucrative career path, a McKinsey survey of next-gen workers found 70% of respondents between the age of 15 and 30 would not or probably would not consider working in mining, the highest of any sector surveyed. Minecraft being the top-selling video game of all-time doesn’t translate to Indeed job applications.

Welders: It should go without saying, but for those of us whose experience in construction mostly involves assembling furniture from flat boxes using Allen keys, large construction projects aren’t fastened together using Allen keys.

Welders play a significant role in assembling and maintaining energy assets, including in the wind industry, where welding is integral in assembling the tower, blades, hub and nacelle. Yet, there is a looming shortage.

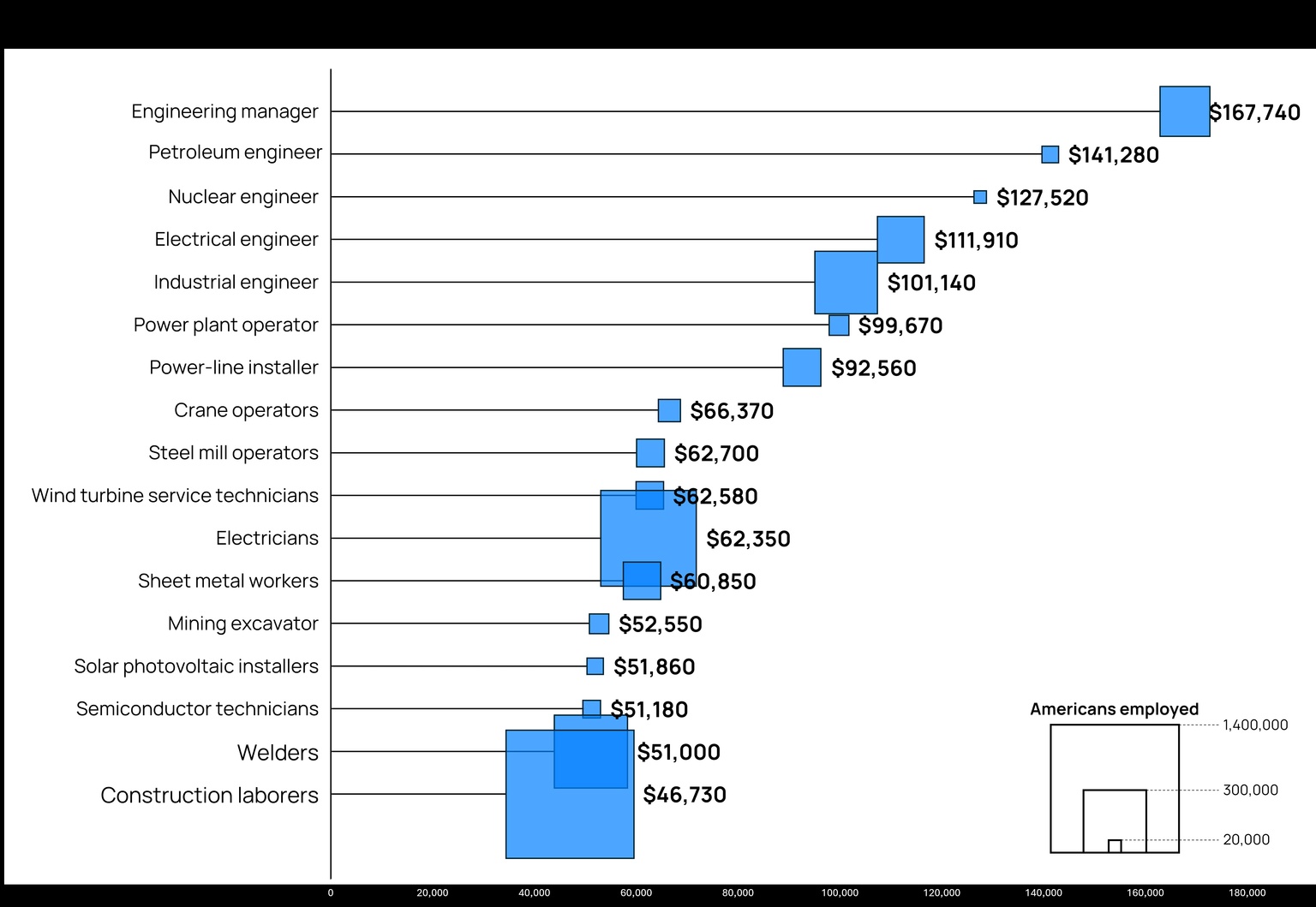

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wage Survey

The US International Trade Commission highlights that more than 40% of welders are over the age of 45 and the country faces a shortage of 360,000 welding professionals by 2027. Canada faces similar challenges with its own welders — currently 81,000 strong, but expected to experience a shortage of 25,000 workers in just five years.

And electricians: Beyond large energy infrastructure — it takes 800 electricians to build a modern data center and ~50 to install a 100-megawatt solar farm — small-scale infrastructure is being electrified, too. It’s estimated that between 60% and 70% of single-family homes in the US will need to upgrade to larger electrical panels for a fully electric home, requiring an army of electricians to accomplish.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects electrician jobs, already one of the largest vocations in North America, will grow 11% by 2033. That’s roughly 80,000 new jobs per year, at a time when four out of every 10 electricians are over 45 years of age. Electrical Contractor Magazine put it this way: the electrical workforce could shrink 14% by 2030 while demand may grow 25% at the same time.

As you might expect, with many of the most critical roles needed for a grand electricity expansion in short supply, there’s competition for existing talent. NextEra president and chief executive John Ketchum spoke of the challenge competition is causing in the company’s recent earnings call.

“It's also proving difficult to reestablish the highly skilled workforce required to build these complex power plants. Gas-fired combined cycle plants rely on approximately 1,000 workers across dozens of niche trades.

“We've learned EPCs are hiring thousands of extra people to address high washout rates with some workers leaving earlier for higher-paying jobs building, for example, LNG terminals, data centers, semiconductor chip manufacturing facilities and other industrial facilities,” said Ketchum.

The good news is that there are several tailwinds helping to grow the trades workforce.

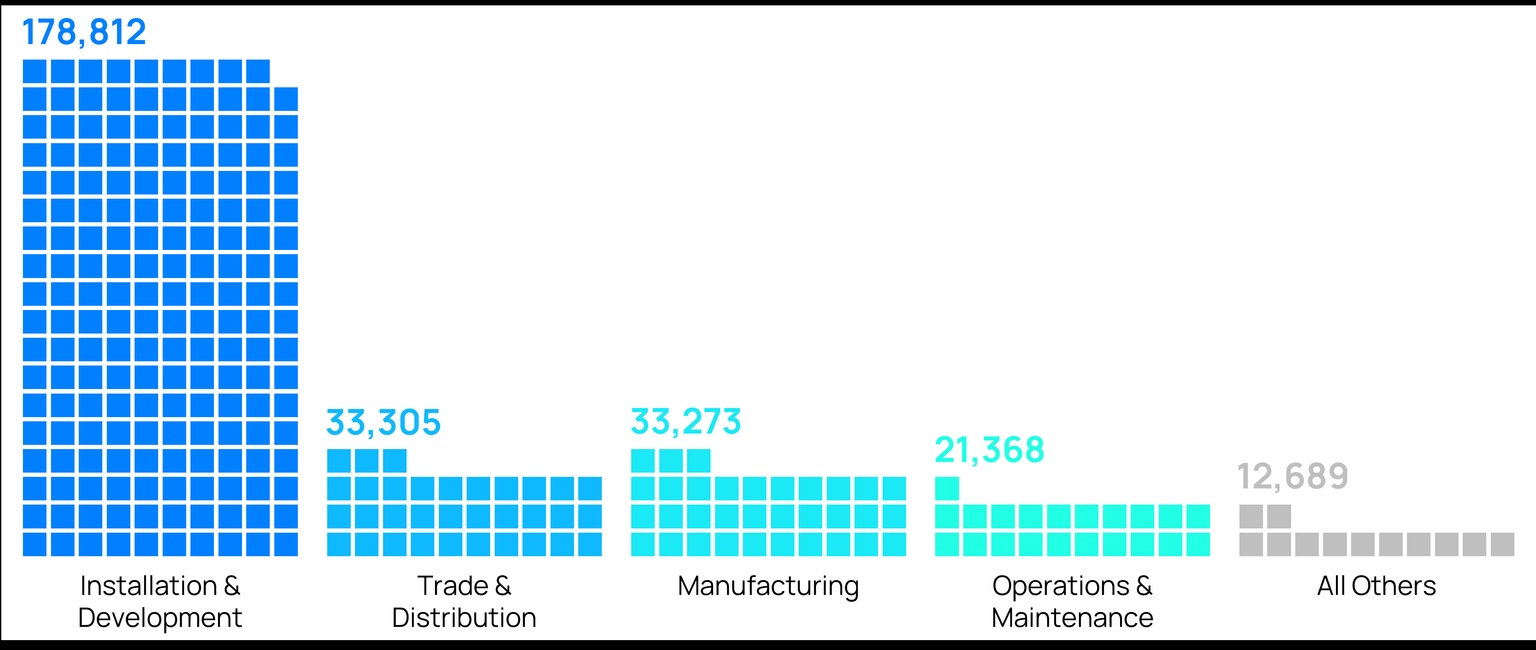

Source: IREC National Solar Jobs Census 2023

Labor lift: For one, college is no longer the be all and end all it once was. In a survey conducted by Gallup, almost half of parents said they’d prefer not to send their kids off to college, even if there weren’t any obstacles, including tuition. And within high school students themselves, two-thirds think they’ll be fine without a college degree.

This might have to do with the looming uncertainty over the impact of AI. Goldman Sachs estimates that 300 million jobs will be lost or degraded by artificial intelligence, with knowledge workers that hail from pricey colleges expected to be the most heavily impacted.

GenZ is increasingly becoming the trades generation. Enrollment in 4-year institutions across the US was flat between 2019 and 2023, while over the same time, vocational-focused community colleges climbed 16%. Even newly-minted MBAs are turning away from traditional post-grad consulting and banking roles to instead acquire “boring businesses,” like welding.

Hurry please: What’s needed right now is urgency — it takes time to develop the “skills” in skilled labor.

Becoming an electrician typically requires six months to a year of in-class instruction followed by 8,000-hours of on-the-job training. A motivated reader of this article deciding here and now to become an electrician might earn their license by the end of the decade. Welders are similar, requiring three-to-five years to be certified, between schooling and practice.

There is support: the US Department of Energy has several programs to develop and expand the labor workforce to meet growing energy needs, while the Government of Canada invests nearly $1 billion every year to support apprenticeships.

There is often a disconnect that exists between the punch-in-the-Excel-formulas desk worker and the real world. The +6% growth factor thrown into cell C9 rarely considers the boots-on-the-ground requirements of large projects, especially in remote areas.

Four hundred electricians were granted temporary visas to Australia last year, as locals weren’t willing to work in the harsh remote locations of some key infrastructure projects. And Tom Mertz, CEO of data center developer T5, said the hiring timelines for key skilled labor roles have doubled from eight weeks up to four months, with future growth rates looking more menacing beyond that.

Bottom line: When FDR came into the presidency, the labor issue he faced was a demoralized workforce looking for any type of work. That is not the situation today.

US unemployment levels are at some of the lowest levels seen since FDR. Countries facing worker shortages like today often rely on immigration to help resolve the issue, yet the White House has instead promised mass deportations, which would further shrink the labor pool, drive up labor costs and ultimately increase power prices.

We’re already seeing a lack of skilled labor contribute to driving up gas turbine prices, so don’t be surprised when labor-related inflation starts hitting everything else.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.