Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

There are big changes coming

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

It’s rare that a single plant drives geopolitics, but it can happen. Piper nigrum is one of the most important plants in human history, playing a pivotal role in naval expansion and exploration. Native to India’s Malabar Coast, this flowering vine produces a cluster of tiny green fruits the size of juniper berries known locally as kali mirch. In the West, we know the fruits as peppercorns.

Depending on when they’re harvested and how they’re processed, the peppercorn’s spice can be manipulated. If the fruit is picked unripe and then sun-dried, it becomes a black pepper, pungent and earthy – the most common type of peppercorn. But left to ripen and then de-skinned, the peppercorn becomes white and has a sharper, slightly fermented taste.

Trade: For much of its history since Europeans became aware of it, pepper has been a highly valued commodity. It was so sought after that the Visigoths demanded sacks of the spice along with silver and gold when they besieged Rome in the 5th century. Nicknamed “black gold” for being traded, at times, ounce for ounce with real gold, Venetian traders had a near monopoly on its trade across the Silk Road. The price difference between the two was described as the “pepper-gold spread.”

The piper nigrum plant with peppercorn fruit // Adobe

But as the old line goes, the cure for high prices is high prices. The luxury-level costs of 15th-century peppercorns drove the Portuguese to seek a route by sea that connected Europe to India to better meet the continental demand for the spice. At the turn of the 16th century, by sailing around the Cape of Good Hope in what is today South Africa, Portuguese merchants were able to secure a supply of pepper and drastically increase Europe’s access to the spice. And while this helped fund a period of great seafaring and exploration, the new deliveries cratered peppercorn prices and broke the pepper-gold price spread.

Fast forward: Like shipping and spice prices, the connection between transportation and agriculture is in the process of being rejoined. As biofuels grow in their role of decarbonizing transportation, commodity prices and global trade are once again in the forefront.

This might be best seen in the bean oil-heating oil spread, more commonly known as the BOHO spread. Influenced by everything from crude oil cycles to Midwestern crop harvests, the biodiesel industry carefully tracks this key metric, and there are big changes coming.

Biodiesel has emerged as a key fuel to help reduce transport emissions. Made using inputs like vegetable oils that are both renewable and biodegradable, biodiesel emits on average 74% fewer carbon emissions than conventional petroleum diesel.

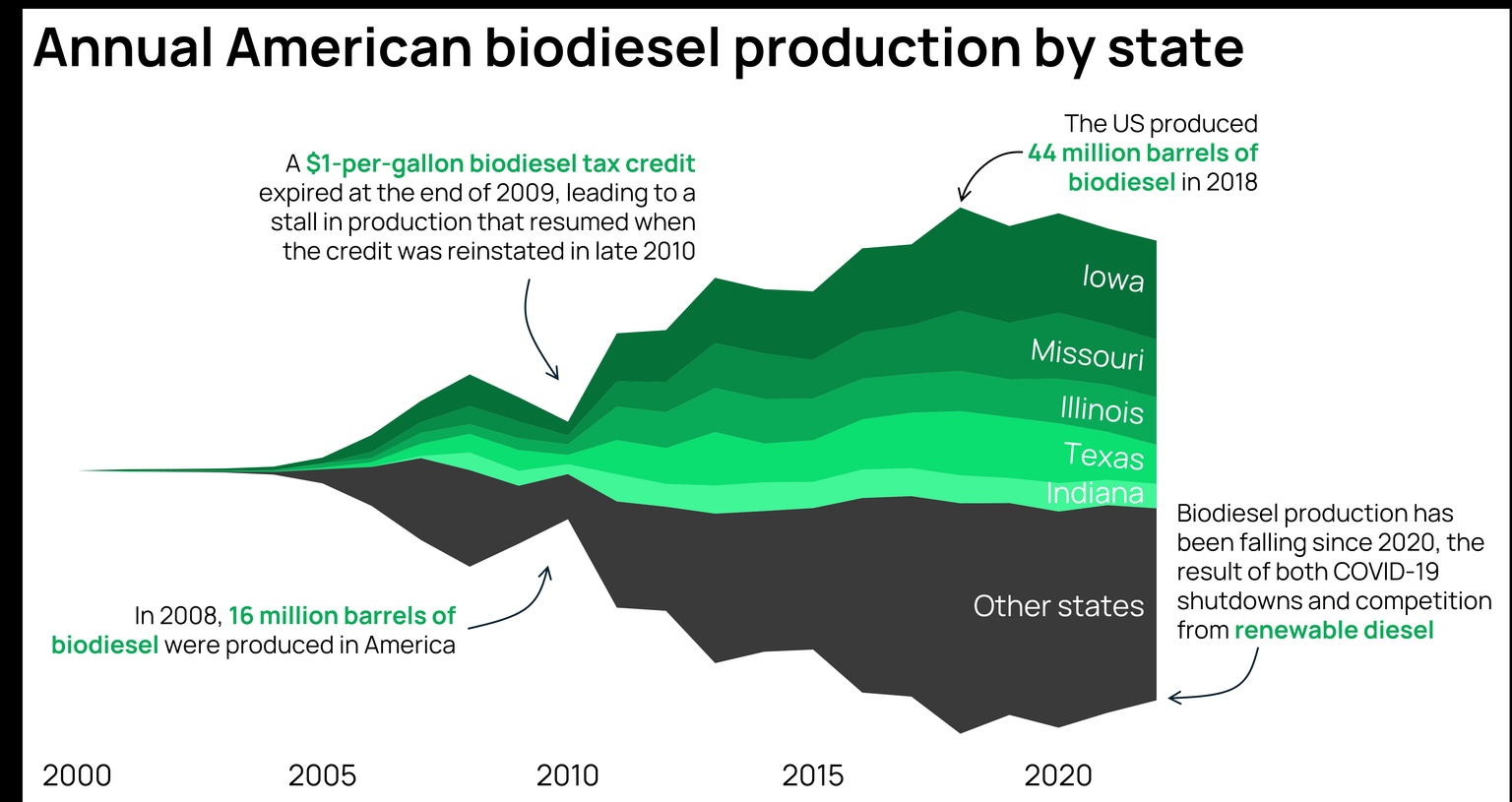

Source: The US Energy Information Administration

The US currently produces and uses ~40 million barrels of biodiesel per year, enough to displace about 4% of American diesel use.

BD vs. RD: Like Jeff Bridges and Kurt Russell, biodiesel (BD) is often mistaken for renewable diesel (RD), another clean fuel. Given that biodiesel is also renewable, it’s a bit of a nomenclature head-scratcher, so you’d be forgiven for getting confused, but the difference comes down how it’s made and ultimately its quality.

Renewable diesel is made using hydrotreatment, a process used in traditional refining that results in a fuel chemically identical to diesel. Distilled in facilities that are comparable to petroleum refineries, renewable diesel is a drop-in fuel that can swap out conventional diesel drop for drop, without blending. Like a Scotch whisky upgraded to perfection.

By contrast, biodiesel is more like a hazy, unfiltered craft beer. Usually made by smaller producers, with a less intricate transesterification process, its higher oxygen levels limit biodiesel to being blended into existing fuel pools. Blending in the US and Canada is typically limited to 5% (labeled on fuel pumps as B5) but can go up to 20% (labeled as B20). The trade-off is price. While not a drop-in fuel, biodiesel is less expensive to produce, selling for ~25% less than renewable diesel in the US since 2020. Blending helps keep prices down.

The economics of producing biodiesel are not simple, especially when it comes to how it competes with conventional diesel. Like a vaudeville performer trying to keep several plates spinning simultaneously, biodiesel producers need to balance several markets, including the price of key vegetable oil, heating fuel prices and tax credits to land the trick.

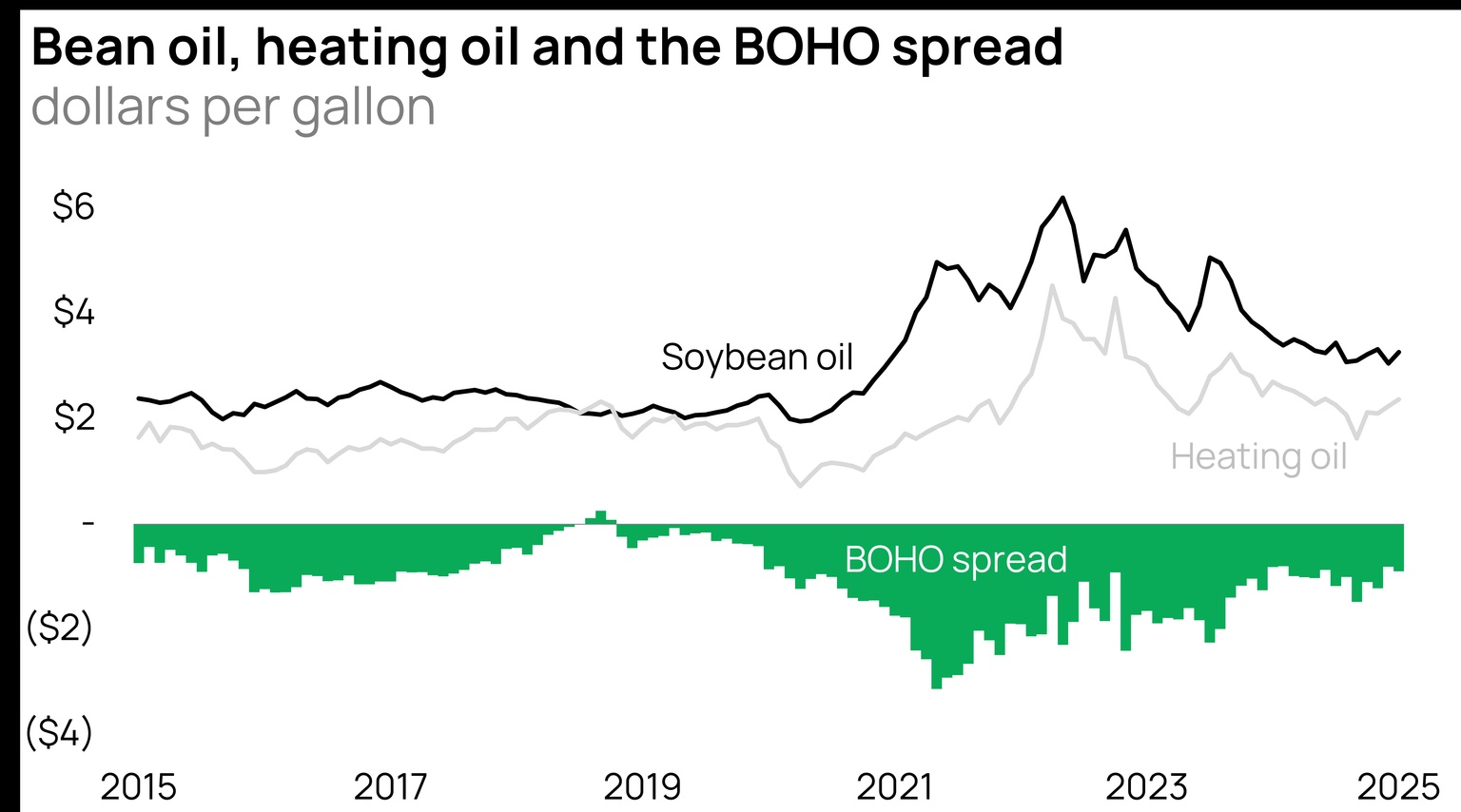

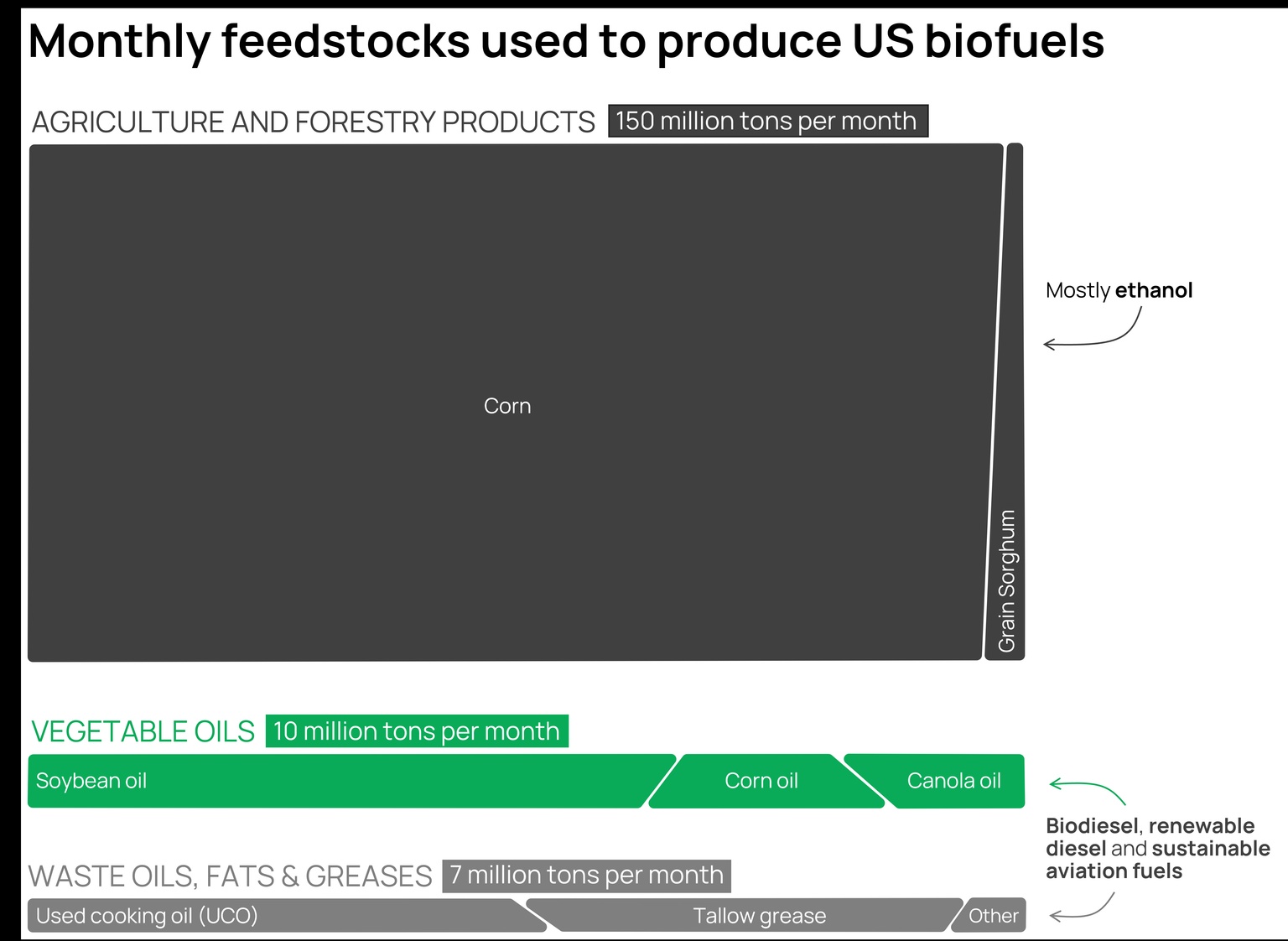

Bean oil: The hops-equivalent for making hazy biodiesel is a range of feedstocks, including vegetable oils and animal fats. The most important one by far is soybean oil, which accounts for more biodiesel production than all other feedstocks combined.

Given that agricultural inputs can account for up to 80% of the total cost to produce biodiesel, producers follow soybean oil prices closely. The price of bean oil, or “BO”, is just half the equation.

Heating oil: The other half is the price of the competition. Biodiesel typically displaces ultra-low-sulfur diesel (ULSD), and heating oil contracts serve as a benchmark for US diesel fuel. The price of heating oil, or the “HO”, reflects what consumers could pay instead of buying biodiesel.

Source: Business Insider, Macrotrends

The difference between BO and HO is the BOHO spread.

Since its peak in 2021, the BOHO spread has been falling. There is no single reason why, but instead is the result of several concurrent events, including American tariffs on China, farmers’ crop decisions, weather and even emerging alternative oils like palm and sunflower oil entering the market. The net result of it all is that the price of biodiesel is now just modestly above its high-carbon alternative.

Astute readers have likely figured out that the BOHO spread is effectively the clean fuel’s premium price over diesel. Unfortunately, being price sensitive, most buyers prefer no premium to diesel, even if it’s better for the environment.

Then what’s the key to enabling biodiesel demand?

Tax credits: In 2005, under the Bush administration, the US enacted the Energy Policy Act of 2005 to combat growing domestic energy problems. Later expanded in 2007 under the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, the policy sets annual renewable fuel volume obligations (RVOs) that refiners, importers and fuel blenders must meet. This allows domestic agriculture to displace foreign oil imports.

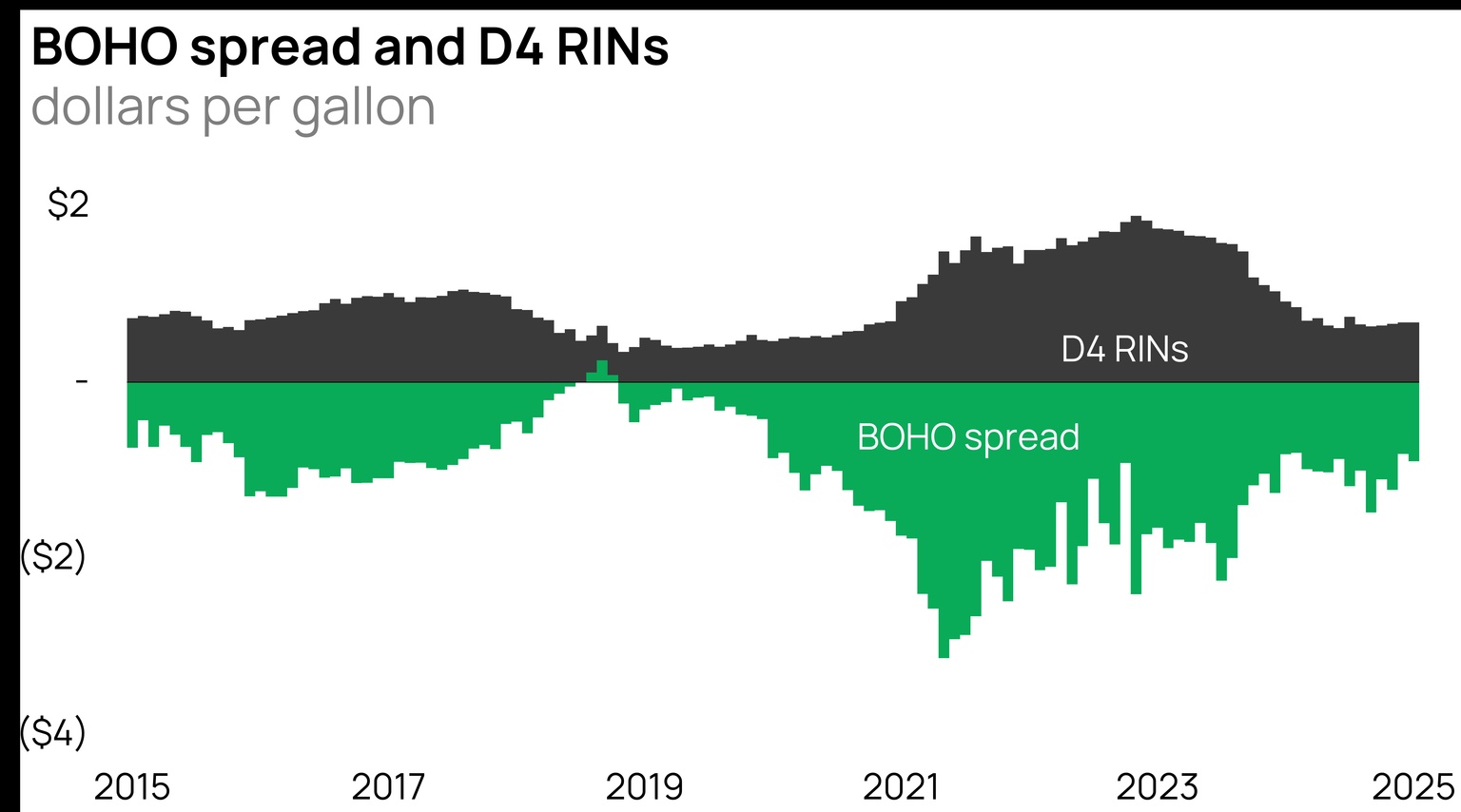

Known as the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets these annual targets. Instead of large industrial refiners like ExxonMobil throwing on some overalls and testing their farming mettle, the RFS allows companies to meet their quota by supporting biofuel producers. Each gallon of biofuel produced generates a Renewable Identification Number (RIN) that can be bought to meet obligations.

Biodiesel generates D4 RINs, which closely track the BOHO spread.

Source: Business Insider, Macrotrends, US Environmental Protection Agency

The D4 RINs act as the financial shock absorbers that largely insulate biodiesel producers from weather, crop yields and diesel prices. Today’s low D4 RIN prices and low BOHO spread reflect low production costs and mean biodiesel is getting competitive with traditional diesel in the market.

Biofuels are facing a period of nearly unprecedented change for the industry.

Credits, geopolitics and competition: On top of the D4 RINs, biodiesel has also historically earned a $1-per-gallon tax credit known as the Blender’s Tax Credit (BTC). The BTC dates to 2005 and has been a steady part of the D4 RIN price calculus. But the Inflation Reduction Act brought an end to the BTC and ushered in a new era of the 45Z tax credit for clean fuels starting in January of this year. As opposed to every gallon of qualifying biofuel earning $1 under the BTC, future credit values will depend on each fuel’s carbon intensity. Most types of biodiesel are expected to earn less than their current credit levels, changing the industry’s calculus.

At the same time, there is increased scrutiny on another key feedstock for biodiesel — used cooking oil (UCO). The US Department of Agriculture describes UCO as the “second most important feedstock” for biodiesel, renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuels. The problem is that the largest supplier of UCO to the US is China, and there is mounting concern about its feedstock’s authenticity. As a result, the new tax credit excludes imported UCO, forcing some producers to seek alternative US-sourced inputs, like soybean oil.

Source: US Energy Information Administration

Lastly, like American preferences shifting from beer to spirits, the biofuels market is also moving away from the hazy, oxygen-rich biodiesel and toward the drop-in renewable diesel. Over the past year, US renewable diesel output capacity grew nearly 20% while output for biodiesel actually shrank by 6%. This dynamic is best seen in California, where three-quarters of the state’s conventional diesel use has been replaced by biofuels, 90% being from renewable diesel and just 10% being biodiesel. Being hazy has its drawbacks.

Like the great peppercorns that helped expand naval transport, the food-transport nexus is reemerging with biofuels. At the center of the complex financial web to support their development is the BOHO spread.

Biofuels are in a state of flux right now, trying to balance commodity prices with tax credits, domestic supplies with foreign imports, and consumer needs with environmental goals. Despite the rapid change, the new Trump administration seems to be supportive of biofuels. They were included in the White House’s list of priority energy sources in its national emergency, and one of the first moves from the new Department of Energy was to approve the disbursement of a $1.7 billion loan for a SAF refinery.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.