Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

How will steel tariffs impact energy?

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Steelmaking is no stranger to tariffs: the industry and companies in it have long benefited and profited from them. So effective were levies in the past, they helped create the world’s first billion-dollar company.

In 1901, the American banking mogul J.P. Morgan welded together three colossal steelmaking firms to create U.S. Steel, then valued at $1.4 billion (roughly $52 billion today). The three companies were National Steel, Federal Steel and, most importantly, Carnegie Steel.

Innovation: It was Andrew Carnegie, the founder of Carnegie Steel, who is credited with transforming the American steel industry into a global powerhouse. His success is often attributed to two great strategic decisions: the adoption of the Bessemer process, an inexpensive industrial method to turn pig iron into steel, and the vertical integration of the industry.

As a result, Carnegie Steel was able to mass produce low-cost steel right when demand was booming during the Gilded Age. Paired with some important connections in the railroad industry, Carnegie found a nearly limitless buyer for his product, laying the foundation for an industrial business so profitable even Ayn Rand would nod approvingly.

But there is more to the success of Carnegie Steel than an improved industrial process and market structure. A third factor that helped propel Andrew Carnegie’s business was tariffs.

A Bessemer converter in Sheffield, England // World History Encyclopedia

A history of steel levies: There were several during Carnegie’s meteoric ascent. The US Tariff Act of 1870, written specifically for steel and fruit, imposed a $28 per ton (~90%) duty on imported British steel rails to help foster American industry and effectively doubled the price of imported steel rails. Levies were further raised by both the McKinley Tariff of 1890 and the Dingley Tariff of 1897, firmly walling off foreign suppliers of steel to the US market. American steel firms profited greatly.

Paired with the vertical integration of mines, railroads, ships and mills, Carnegie and the other steel magnates could optimize industry costs with no fear of foreign competition.

As the deal to buy Carnegie Steel closed, J.P. Morgan reportedly told the steel magnate, “Mr. Carnegie, I want to congratulate you on being the richest man in the world.” He wasn’t lying. As recently as 2011, Andrew Carnegie still ranked as the second-richest American of all-time, behind only John D. Rockefeller.

But despite how pivotal tariffs were to the early American steel industry, Carnegie eventually came to despise them, arguing they hampered innovation.

In spite of his warnings, steel protectionism has returned to America.

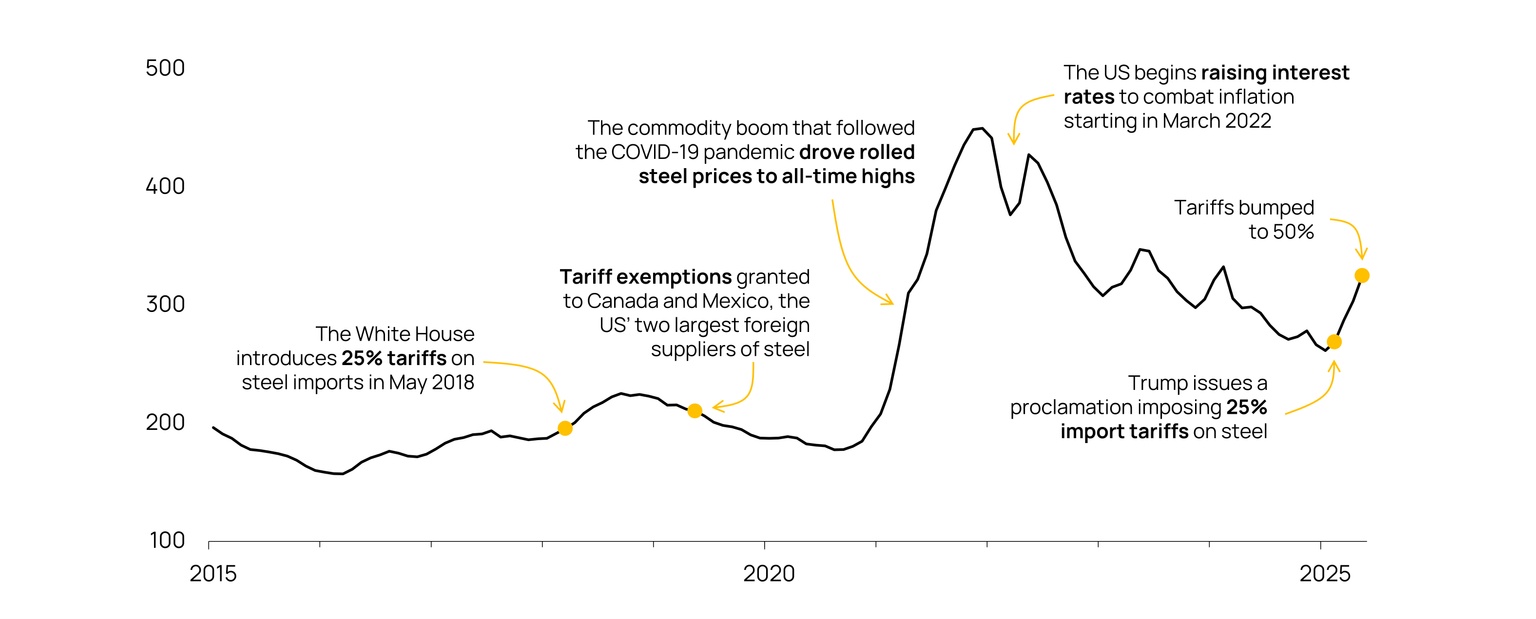

Back into the tariff crucible: In his first term, US President Donald Trump ordered a 25% tariff on imported steel alongside a 10% tariff on aluminum. Since then, levies on steel have been a moving target, but were further raised to 50% earlier this month.

For consumers of steel, including energy companies, the tariffs complicate supply chains and drive-up projects costs for both clean and conventional energy. And economists have long debated whether forcing steelmaking back home is truly a win for the economy.

So, how will steel tariffs impact energy? Let’s forge ahead and find out.

Steel is the hidden backbone of today’s society. The metal alloy is listed by energy researcher Vaclav Smil as one of the four material pillars of the modern world, alongside ammonia, cement and plastic. The world produces nearly two billion tonnes of steel annually with the energy industry being big users.

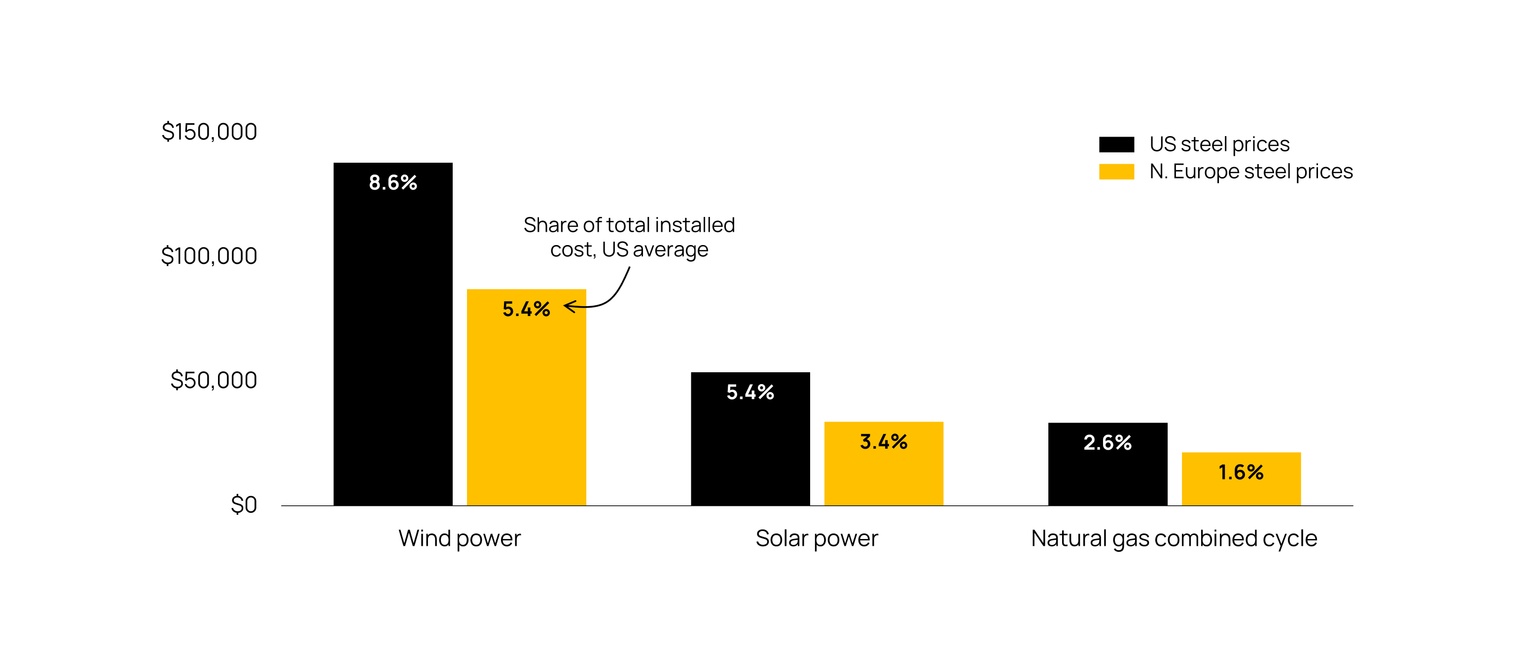

Take a wind turbine, where a sturdy tower is needed to withstand high winds for several decades. Steel accounts for between two-thirds and three-quarters of the total material mass of an onshore turbine, with the analyst Steel for Fuel estimating that the metal accounts for between 5% to 9% of the total cost of a turbine.

Source: Steel for Fuel

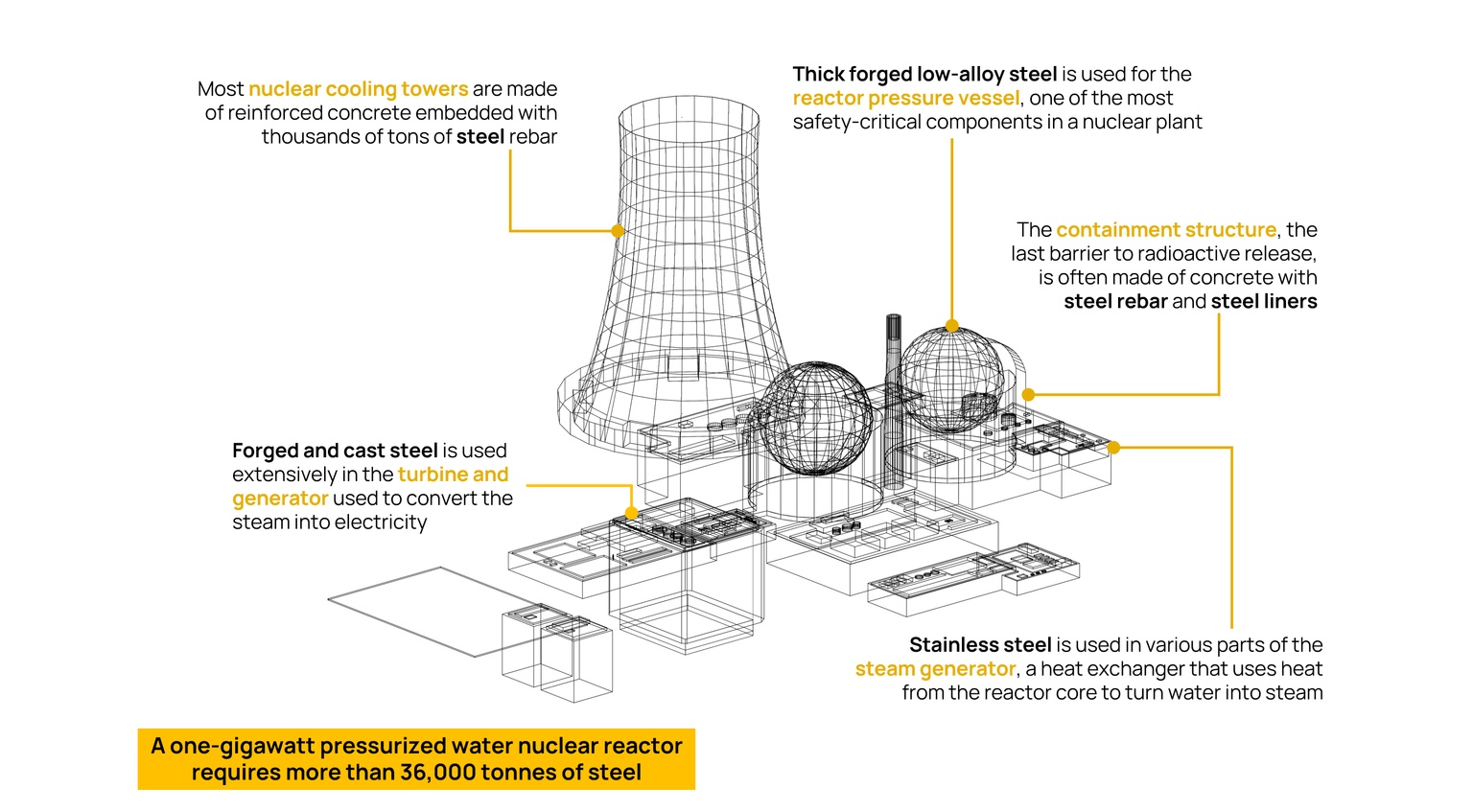

For nuclear plants, steel is not just the bones of these large facilities but one of the primary means of keeping the public safe in the case of an accident. Specially manufactured high-quality, low-impurity steel is needed to meet the extreme demands of an operating nuclear plant, the difference between industrial-grade and nuclear-grade steel being about the difference between Jesse Pinkman’s “Chili P” and Walter White’s “Blue Sky.”

The World Nuclear Association estimates a Generation II pressurized water reactor will need 36,000 tonnes of steel for a one-gigawatt plant, half what was used for the Golden Gate Bridge.

Others: While solar power uses less relative to wind and nuclear power, racking and mounting structures that support the solar panels still use meaningful amounts of steel, not to mention aluminum (also facing 50% tariffs).

As for oil and gas, geothermal and anything else that requires production from the beneath the Earth’s surface, steel is found in abundance in drill strings, casing and pipelines. Materials, largely steel, account for between 30% and 40% of the cost of a pipeline, including those needed in the energy transition to move hydrogen and carbon.

Needless to say, given how much steel goes into various energy projects, any increase in the price of steel is likely to flow through to energy prices.

Unlike today’s levies, which have been applied directly by the president, protections for the American steel industry in the late 1800s were enacted as laws by Congress. They were highly effective in jumpstarting the young industry domestically.

By applying a hefty import tax, steelmaking startups were protected from cheap imports by the dominant producers of the day in Europe, especially Britain. This gave room for companies like Carnegie Steel to develop their own supply chains and economies of scale.

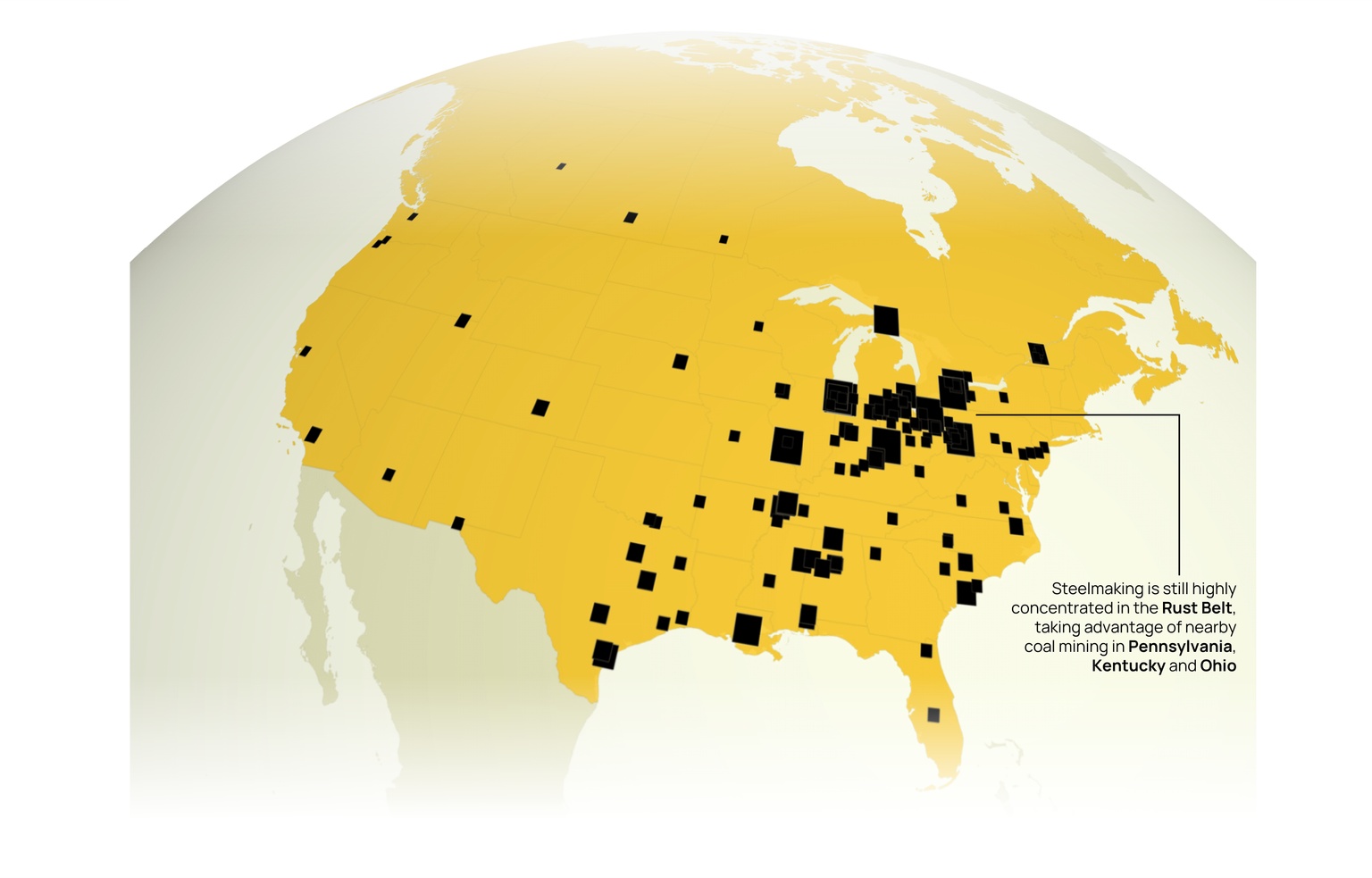

Source: Global Energy Monitor

But while tariffs made steel kings once upon a time, biting the forbidden fruit of protectionism is unlikely to bring economic paradise back this time. The US steel industry of the Gilded Age is not the steel industry of today, now mature and high cost.

What’s different? For one, North American steel plants are no spring chickens. The average age of operating plants in both the US and Canada is about 57 years, according to Global Energy Monitor. While many of them have been modernized, they often lack the flexibility or locational advantage that new plants in developing nations benefit from for international trade.

And unlike Andrew Carnegie’s labor force, today’s steel workers are both well paid and unionized, with good pensions and benefits. Great for workers, but less so for global competitiveness in a highly commoditized industry. Ayn Rand would arch an eyebrow in disdain.

Unlike the tariffs of the late 1800s, which were enacted by Congress, the latest salvo of levies on steel imports were initiated by the president in his first administration under what’s known as Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. This gives the president the authority to adjust the imports of goods based on national security.

The numbers: Tariffs of 25% were set unilaterally across all steel imports by the White House in 2018, before it relaxed them for Canada and Mexico under the US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement a year later. The Biden administration kept some of the levies in place, but negotiated deals the EU, UK and Japan. Then, back in office, President Trump reapplied the 25% rate to all imports before hiking it to 50% earlier this month.

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of steel tariffs today.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data

Economics: Tariffs produce something economists call a distributional conflict, where the impacts are felt differently across the economy, creating winners and losers. Steel producers may see a benefit, but it’s consumers who will be hurt.

In 2002, President George W. Bush imposed tariffs of 8% to 30% on most steel imports to protect the industry from cheap imports (familiar?). Tariffs meant to last three years were lifted after just 20 months due to their negative impact on the economy. That included the loss of 200,000 jobs in the steel-consuming sectors, more than the entire US workforce in the steel industry at the time.

Going back to the Great Depression, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act introduced duty increases of 23.7% on steel imports to protect American steelworkers and help the contracting economy of the time. In retaliation, Canada slapped its own tariffs on US steel (just as Prime Minster Mark Carney did recently), while France, Britain and Germany turned to each other for steel. American steel exports dropped by three-quarters and the domestic producers that were meant to be protected by tariffs were instead cut off from the most important markets in the world at the time, further aggravating the Great Depression.

And even the steel tariffs from Trump 1.0 saw distributional conflict. A study from the Peterson Institute found the 2018 levies cost steel-using industries about $650,000 per year for each job saved in the steel industry.

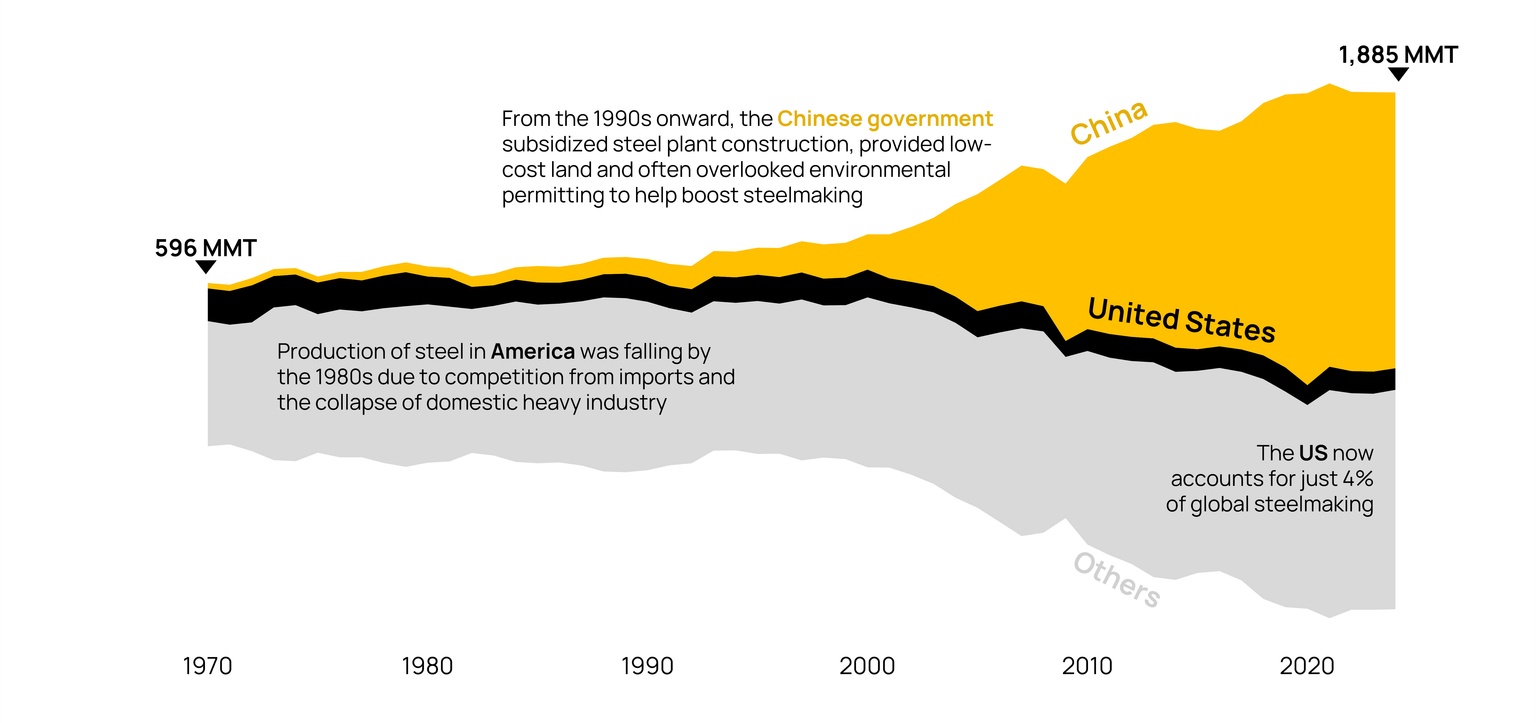

Source: Data from World Steel Association, compiled by YouTube channel Statistics and Data

What do all the recent uses of steel tariffs have in common? They all tended to protect a narrow sector but imposed broader costs on the rest of the economy.

The richest irony of the story is that Andrew Carnegie, made to be the second-richest American up to until at least 2011 in great part because of tariffs, became an ardent opposer of them. He believed tariffs should “nurse an industry to health, not to addition.”

And tariffs aren’t a Trump or a Republican problem: they’re bipartisan. Despite all the screaming from Democrats when the original Trump tariffs were announced, the Biden administration kept many of them in place and even imposed others with its turn in office.

On energy: In classic distribution conflict form, tariffs will materialize in customer pain.

Back in April, prior to levies being raised to 50%, Ørsted was projecting significant cost increases to its power projects in the US, notably the two large offshore wind projects: Revolution Wind and Sunrise Wind.

And last month, when tariffs were yet to reach today’s levels, US shale producer Diamondback Energy specifically called out steel tariffs as being a barrier for bringing on new oil supplies.

More broadly, at the original 25% tariff rate, the combination of steel and aluminum levies was expected to increase the tariff burden on the energy, utilities and resources industries from $400 million annually up to $53 billion, according to PwC’s US Tariff Industry Analysis. That has undoubtedly gone up with the latest levy increases. All this as power prices are set to rise from data center demand in a technology race with China fueled by electricity.

Bottom line: As Milton Freedman once said in a lecture at Kansas State University: “If we impose a tariff on steel, or restrict imports of steel in other ways, the people who benefit are visible and clear and available and apparent. They have a very strong interest to press for restraints in that respect. The interests of the rest of us are very diffuse. Each of us will pay a few pennies more.”

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.