Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

What is the energy use impact of humanoid robots?

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

At the height of the Renaissance in late 1495, Ludovicio Sforza held an extravagant feast in his Italian court, a common occurrence for the Duke of Milan. The lavish feast paired with live music and entertainment was the 15th century equivalent of virtue signaling, meant to showcase Milan’s cultural dominance amid one of history’s great cultural periods.

In attendance at the party was an increasingly notable artist and inventor, eager to begin work on his upcoming painting, The Last Supper. But on this night, the talk of the party was centered around a suit of armor. There was no knight hidden inside the traditional Italian battle gear, but it could nonetheless sit down, stand up, move its arms, turn its head and reportedly even lift its visor.

This robotic knight was the latest creation of 43-year-old Leonardo DaVinci, at the time deep into anatomy, engineering and hydraulics. He was working under the patronage of the duke to both design war machines and create masterpieces. It was peak Leonardo.

A recreation of Leonardo’s robotic knight from drawings // Invisible Not Broken

In the 1950s, a notebook from DaVinci was recovered containing descriptions on how the robot knight was designed to work. NASA roboticist Mark Rosheim would later use those to recreate the 15th century automaton, which proved to be fully and astoundingly functional.

Fast forward: It’s not just Renaissance polymaths who are fascinated with human-like machines: from Rosey the Robot vacuuming Elroy Jetson’s room to C3P0 repairing galactic warp drives, the idea of useful robots that kind of look like us have long captured the human imagination. And, depending on your proclivity to living alongside them, we may be the generation lucky enough to see those fantasies come to life.

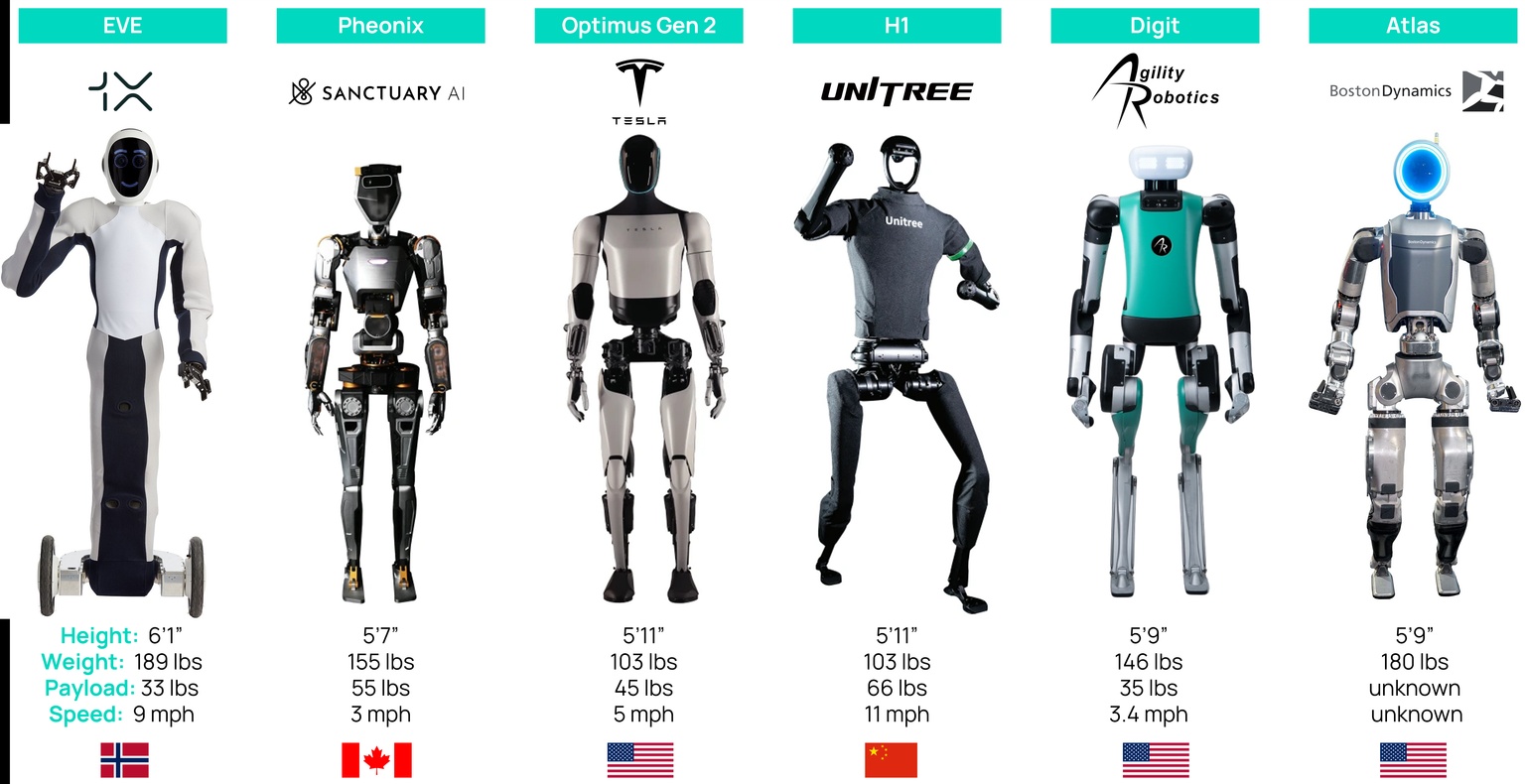

Over the past 12 months, there have been several high-profile announcements in the humanoid robot space. During Tesla’s We, Robot event last October, a battalion of the company’s Optimus Gen 2 bots walked out and among the crowd, dazzling the audience. In April, six different robots completed the Beijing half marathon, a world first. And over the past year, 1X, Unitree, Figure AI, Boston Dynamics, Unitree, Apptronik, EngineAI and realbotix have all released working robot models, many of them for sale.

Data from Morgan Stanley

It no longer looks like if but when these machines become a mass consumer product, put in motion both literally and figuratively by DaVinci. Between 2022 and 2023, a combined 15 humanoid models were unveiled around the world. But last year alone, that jumped to 51, many with the promise to help with mundane domestic chores and tasks. On the energy side, a wide adoption of robot helpers would have no small impact on electricity use at home and on the grid.

So, are humanoid robots here and what will they mean for energy use if they are?

Let’s plug into the matrix.

The first mental hurdle to get over is whether your average household would ever be willing to fork over the tens of thousands of dollars needed to purchase their own humanoid robot. The answer in many cases will probably be yes.

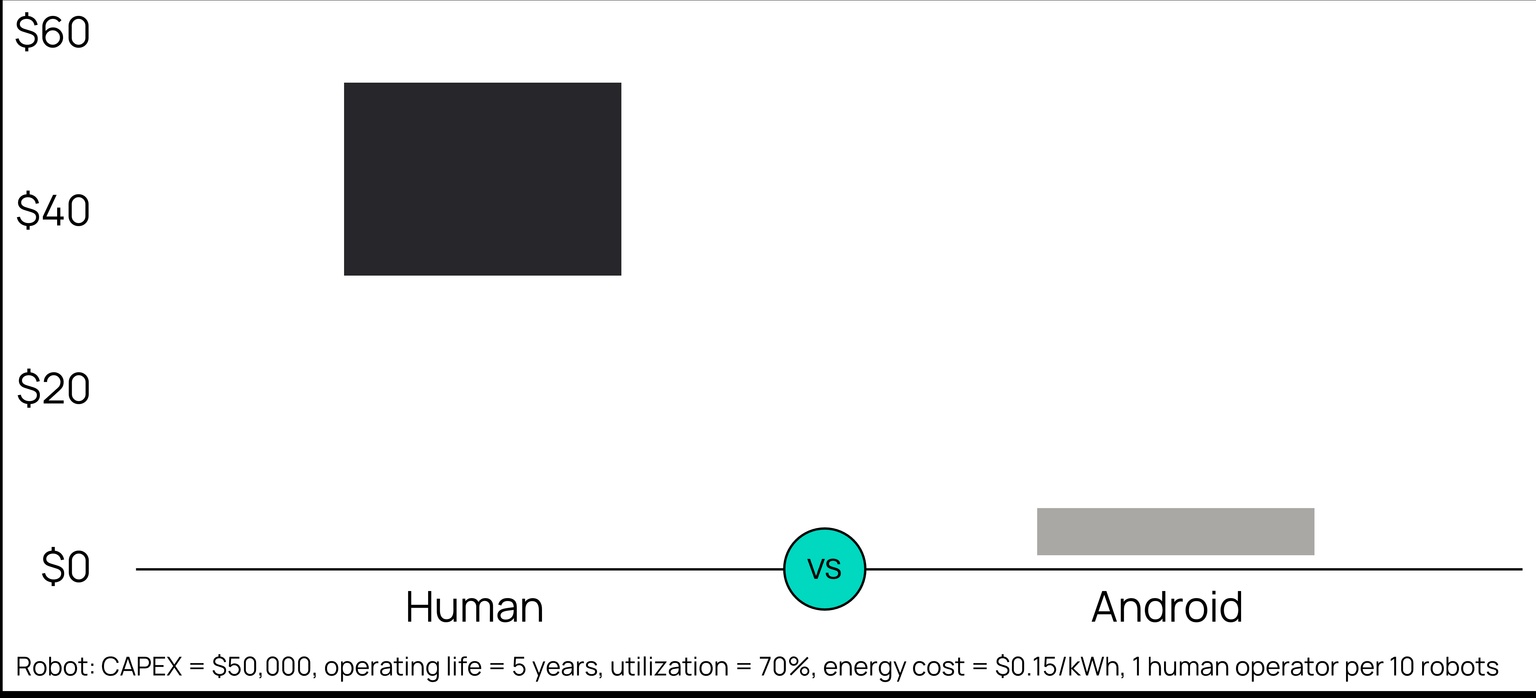

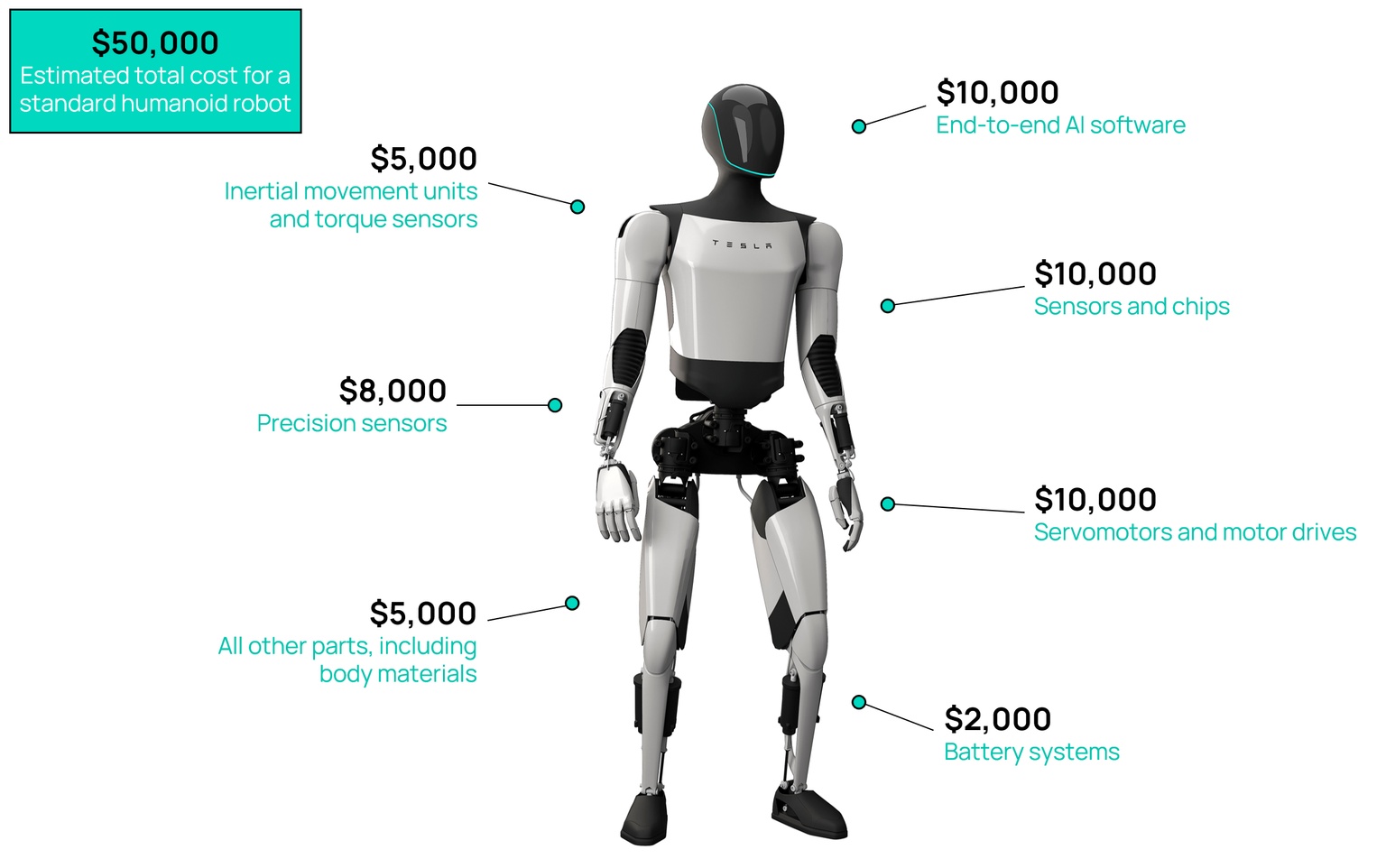

Estimates: Groups like Morgan Stanley and Global X place the cost to build a Tesla Optimus Gen 2 today at $50,000, roughly the price of a brand new BMW 3-Series. Let’s assume that’s the retail price and the cost is spread out over a five-year operating life — $10,000 per year or $833 per month. That’s approaching what some families already spend bringing in a housecleaner every couple of weeks. But this cleaner would be there every day and can do additional day-to-day tasks like cleaning the kitchen after dinner and doing laundry. There’s real value there and those prices are likely to come down further.

Analysis by Steel for Fuel

Cost estimates fall even further if households get extended use out of the bots or if the price were to come down to $20,000 — the target Elon Musk has predicted. BYD says it will start deliveries of a $10,000 model later this year (!).

The cheap labor aspect goes beyond my back-of-the-napkin math. Steel for Fuel highlights that the hourly cost of a robot is likely one-tenth the rate of human labor, if not cheaper. RethinkX believes the labor rate of robots in 2025 is $2 to $10 per hour. And Rob West over at Thunder Said Energy found industrial robots have an average payback period of 1.5 years and a very healthy 60% rate of return for the companies that deploy them to replace workers.

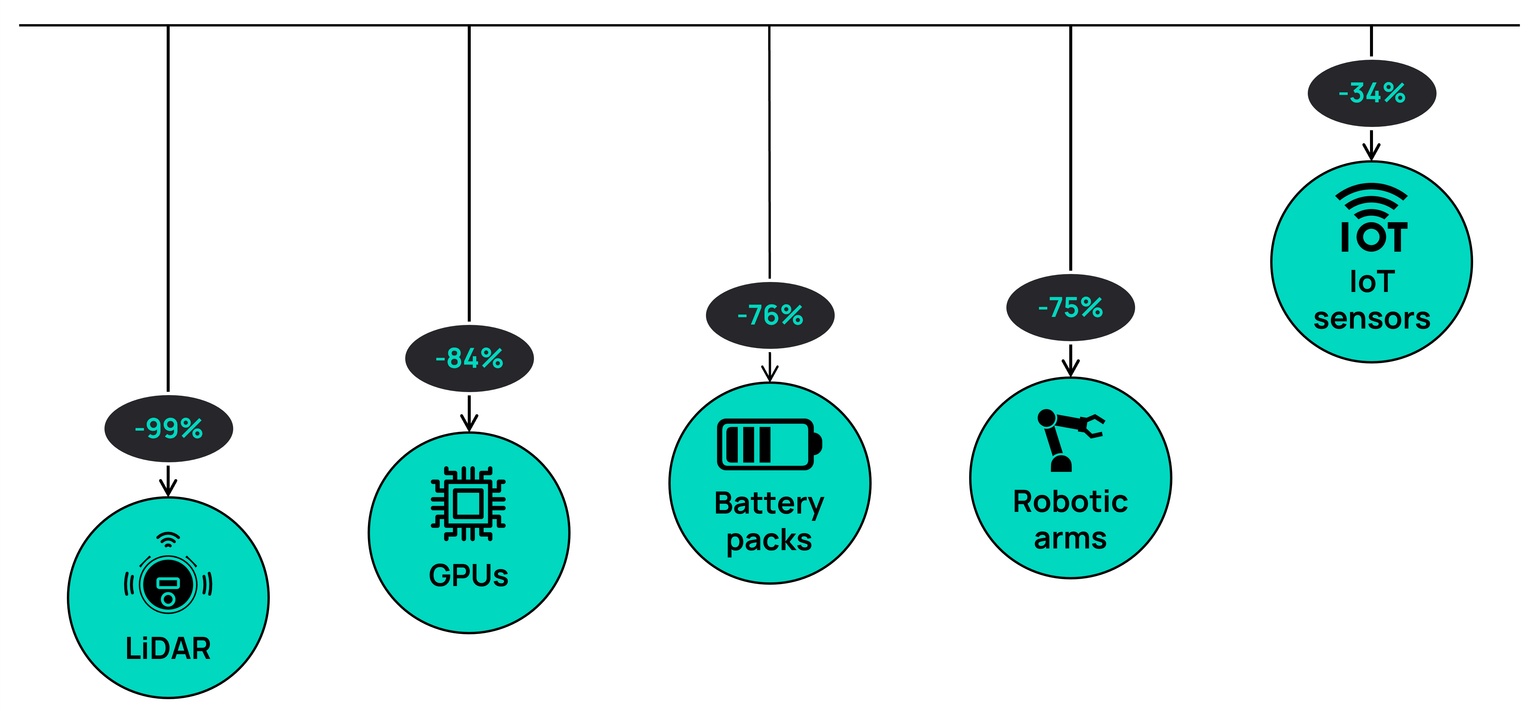

Price reprogramming: Robotics are here because they’ve benefited from a wave of other maturing industries that helped drive costs down for some of their key components. Autonomous vehicle initiatives like Waymo and Baidu Apollo Go have brought down the price of LiDAR enormously. AI has helped bring GPU costs down while battery prices continue to fall from the growing energy storage markets. And with our world becoming an ocean of connectivity, the price of sensors for the internet of things is falling, too.

But if the economics are so compelling, why aren’t astro-butlers everywhere?

The difference between a generalized robot that can communicate and tackle many tasks in a chaotic home environment and an industrial robot doing the same task over and over is about the difference between a Starbucks barista and a Keurig machine.

Excitement over Elon’s We, Robot battalion march faded when it was revealed there were human operators for each of the bots working behind the scenes. And as the New York Times highlighted in an article last month, 1X’s robot, Neo, is currently in home trials, but with Norwegian technicians usually hanging out in the basement pulling the strings.

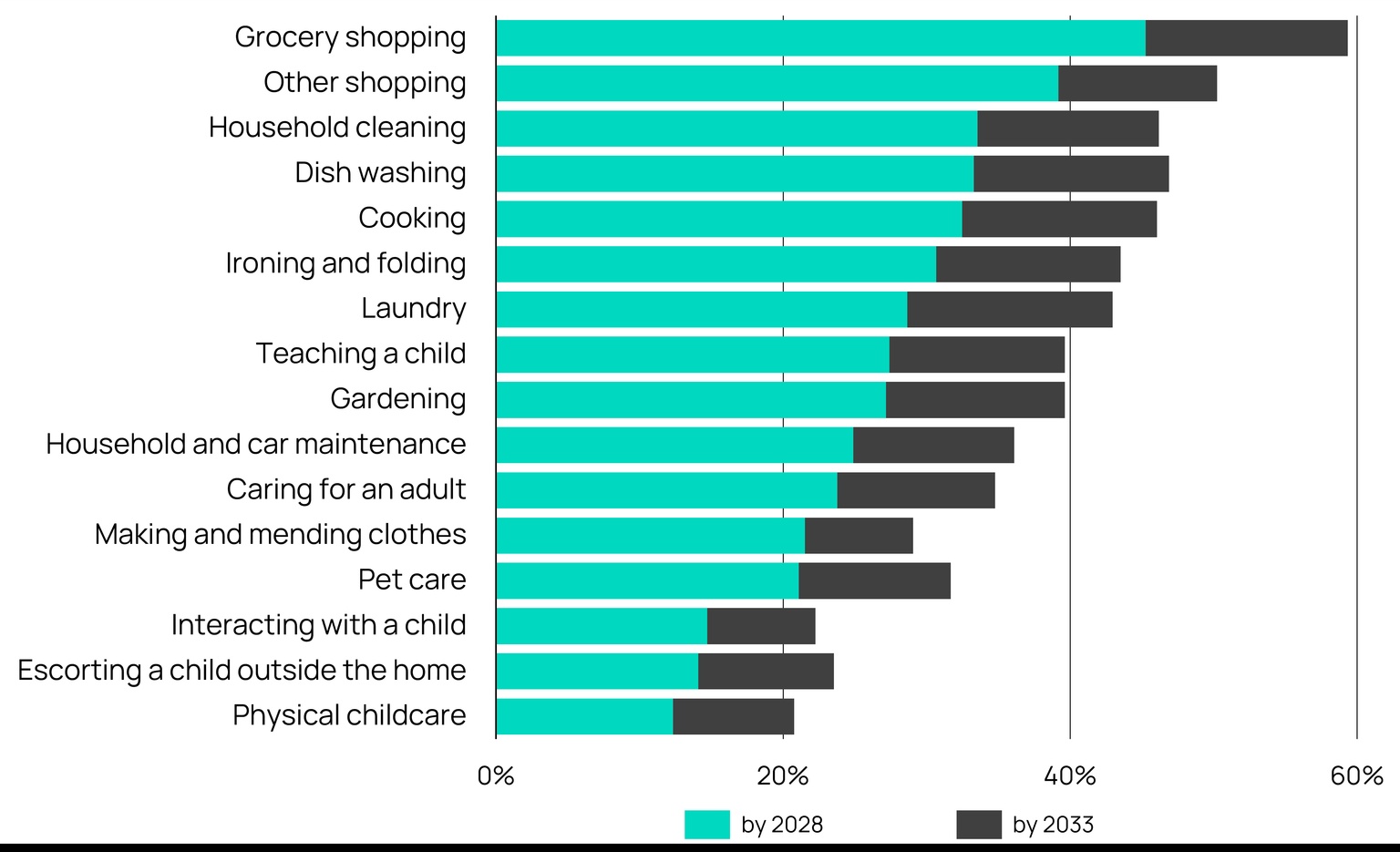

Survey of industry experts conducted by PLOS One

Don’t lose sight of the trend: robots won’t work like the Wizard of Oz forever. What’s missing but in development is the next big thing in AI: large world models.

LWMs: Chatbots like ChatGPT have revolutionized how to ace high school essays on Hamlet by studying text culled from the internet to create large language models. Similarly, robots will learn how to walk, clean dishes and sow petunias by culling the internet for images, audio files and videos. Large world models (LWMs) will give androids a way to understand and predict how the real world works, so they can move, interact and make decisions like humans. As Cristóbal Valenzuela, CEO of AI startup Runaway, put it in an interview with TechCrunch: “With an advanced world model, an AI could develop a personal understanding of whatever scenario it’s placed in, and start to reason out possible solutions.”

Various companies are working on large world models. Google’s DeepMind recently showcased how its Genie 2 LWM works and Nvidia’s Cosmos is reportedly the most advanced in the world.

Data: Forbes, Clean Technica, BNEF, Stanford University’s AI Index Report

The mass consumer market of humanoid robots will be here when cheaper machines meet more advanced large world models, both of which are not far off.

The two dimensions to think about the energy use of androids are their power draw at home and model training at a grid level.

Home use: It’s still unknown exactly how much an average home robot would use for power, but RethinkX estimates it to be 10 kilowatt-hours per day. To put that in context, that’s a third of your average American home’s daily electricity use, or roughly the consumption of a typical electric car.

If there were 100 million androids working regularly across the US, it’s believed they would need 400 terawatt-hours of electricity a year or ~10% of today’s total US power consumption.

The grid: If you thought training large language models required a lot of power and data centers…

Given the inputs to the models would be multi-modal — incorporating audio, video and text — the computational needs of large world models would likely be enormous. Simulating environments with physical dynamics and real-time responsiveness can require petabytes of data and GPU clusters for both rendering and physics.

As TechCrunch put it: “Training and running world models requires massive compute power even compared to the amount currently used by generative models… [They] would require thousands of GPUs to train and run, especially if their use becomes commonplace.”

Modified from Global X, Morgan Stanley

And while that sounds like a big hill to climb, David Sacks, the White House’s Crypto Czar, recently highlighted how fast AI data crunching is advancing.

“Where people don't understand exponential progress is that if you're getting better at 10x every two years, that doesn't mean you'll be at 20x in four years. It means you'll be at a hundred X. So, the models, the chips, the data centers will all be a hundred times more powerful in four years, let's say at the end of this presidential term… multiply those things together, you're talking about a million X increase,” suggested Sacks.

There is no shortage of tech evangelists who believe that consumer-level humanoid robots are on the horizon. During his speech at this year’s Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang told the crowd, “the ChatGPT moment for general robotics is just around the corner.” And Morgan Stanley sees annual revenues for androids just sold in the US hitting $1 trillion by 2050.

But there is also likely no shortage of people who will never consider hosting anything human-like with an artificial mind in their homes.

Some perspective: Early household appliances were met with significant public concern before their eventual widespread adoption. A basic lack of understanding about electronics fueled fears and misconceptions, even leading to some hilarious comparisons between appliances and modern witchcraft.

But appliances ended up as great liberators. The average household in 1900 spent nearly 60 hours per week on housework. That dropped to just 18 hours by 1975, largely thanks to electronic appliances. This liberated the traditional homemaker — the vast majority women — and helped drive up female participation in the labor force.

Humanoid robots represent the next step in liberating people from mundane housework and labor, something there’s clearly a market for.

It’s also remarkable that today’s models look very similar to Leonardo’s 500-year-old robotic knight. Who knows, maybe Elon is about to paint a masterpiece.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.