Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Development is not as easy as it used to be

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Solar power is unquestionably getting harder to develop.

Let’s rewind the clock back to 1982 in California’s Central Valley, and ARCO Solar Inc. flips the switch on North America’s first commercial solar project. The 1-megawattHesperia photovoltaic power plant next to the Lugo substation turns on and begins delivering power to California’s grid. It performs so well, the company quickly builds a 6megawatt plant further to the north in Carrizo.

For ARCO, of all the challenges working with the new power technology, getting connected to the grid wasn’t one of them.

Growing smaller: The 1980s was a time when most power plants being added were large and centralized, so the number of connection requests grid operators received was low. Approvals, straightforward. Full environmental impact assessments, as rare as local opposition to projects.

It was a time the public was excited about solar’s potential. Partially in response to the oil crises of the 1970s driven by Middle Eastern oil embargos, President Jimmy Carter installed solar water-heating panels on the White House, emphasizing “nobody can embargo sunlight.”

Solar panels being installed on the White House roof // GetArchived

Many of today’s issues weren’t on the radar. The closest the 1980s came to saying “duck curve” was the 1984 release of Nintendo’s Duck Hunt. Issues like curtailment, negative pricing, and spray-and-pray development strategies weren’t on the minds of early solar developers.

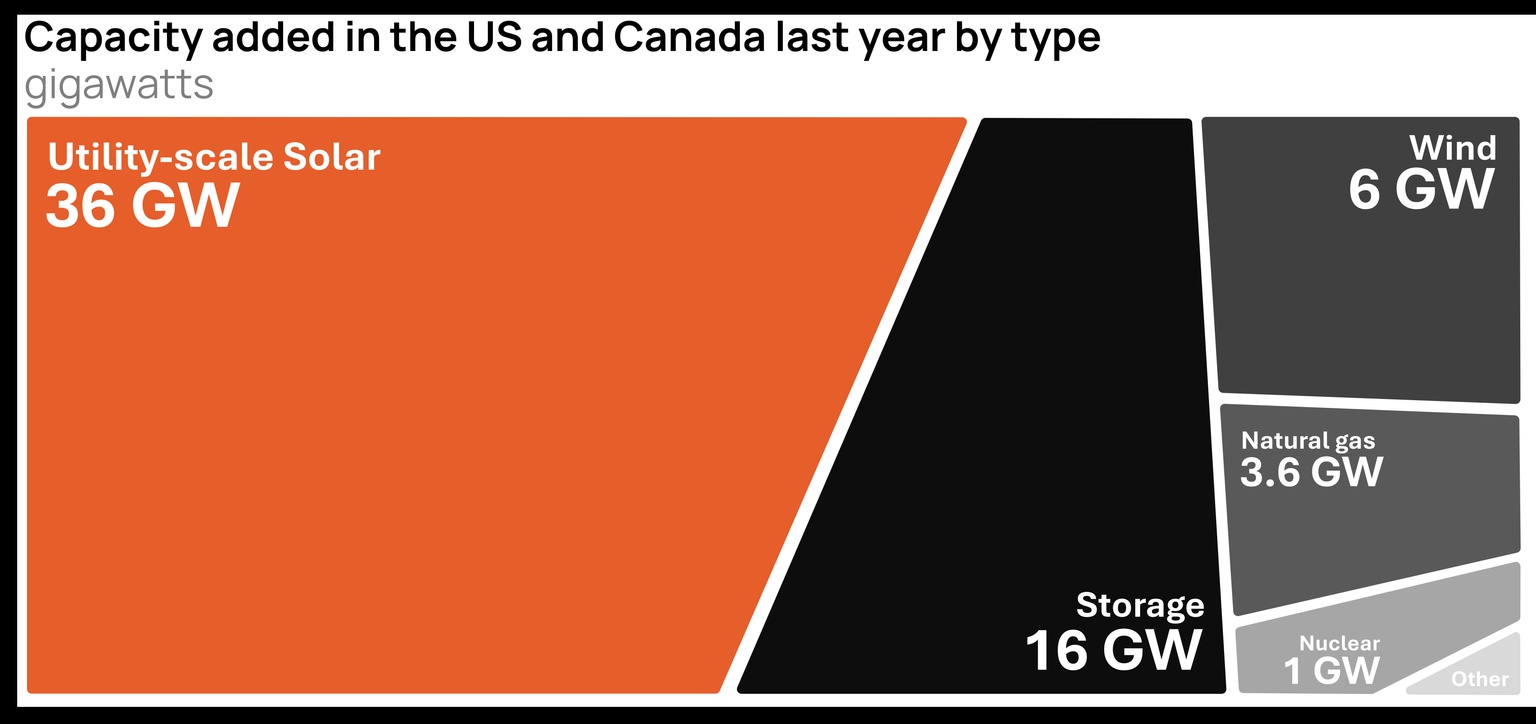

Fast forward: While the production of solar panels has become easier over time, figuring out where to place them has become much harder. Solar was the single-most installed capacity source across North America last year, but its scale introduces new challenges.

Nowadays, to develop a project requires a development trifecta — an interconnection agreement, permits and a land agreement. And to attract investment in the project, the revenue potential needs to be there to justify it.

Victim of its own success, solar’s growth has made each of these four project essentials harder. In 2024 alone, nearly 600 new solar PV projects came online across the US and Canada. This year, that will likely jump to more than 700. So how do modern solar developers get these projects across the line?

To start with, just turning on a simple light is often taken for granted. The grid is a marvel of engineering and often considered to be the most complicated machine on the planet: Electrification was named the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century by the US National Academy of Engineering. Adding a new power source to the grid is like adding an intermediary step to a trillion-dollar Rube Goldberg machine, so requires careful study.

How it’s done: For the right to connect to the grid, a new project first needs to join an interconnection queue.

Joining a queue kicks off an elaborate process by grid operators that starts with a feasibility study to understand how a project will affect the grid and whether existing infrastructure can even handle the new generation. This is followed by a more rigorous impact study to stress test and see how the project might affect reliability and create other grid issues like congestion.

Source: Orennia

What comes out of the studies is either a thumbs down or a thumbs up, along with technical requirements and cost estimates for any upgrades to the grid needed for the project to connect.

If all is hunky-dory, contracts are signed and an interconnection agreement between developer and grid operator is achieved. Champagne is popped.

Spray and pray: The process to obtain an interconnection agreement was designed for an age gone by, designed when fewer but larger power plants were the focus. But due to both a huge influx of smaller projects and a lack of resources for grid operators to study them, a typical project will now spend an average of five years waiting for an interconnection agreement. This compares to just three years applying to the queue in 2015 and less than two back in 2008.

A lot can happen in those five years. The lay of the land can be quite different from when a project enters a queue compared to when it exits, which leads most projects to either not get an agreement signed or to get mothballed beforehand. At Orennia, we estimate new renewable projects have a ~60% chance of eventually signing an interconnection agreement. That is not high and has led companies to add more projects to the queue than they realistically expect to get built, often referred to as a “spray and pray” strategy.

It'll come as no surprise to readers that spray and pray results in even worse interconnection queues for projects, taking a shortcut that doubles the trip.

The remedy: There are a couple. The first is reforming the process, something already underway. Two years ago, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued an order to move toward studying batches or clusters — evaluating requests as a group to speed up the process and increase the cost of it to deter speculative applications.

The second is for developers to be more thoughtful on where to site projects. By better understanding where transmission bottlenecks are forming and which other projects are advancing through queues, sites can be picked that have a better chance of surviving the interconnection gauntlet. Consultants rejoice.

There is a wide array of permits needed for solar projects, ranging from state and zoning to building and road approvals. Of the bunch, the two most challenging to secure are local and environmental permits.

Throwing shade: Apart from securing a lease from the owner(s) of the land hosting the panels, there needs to be some buy-in from the local community. It’s no secret that NIMBYism in rural areas is affecting energy development.

The US Department of Agriculture estimates that 70% of commercial-scale solar projects built between 2012 and 2020 were done on agricultural lands. And a survey conducted last year by the American Farm Bureau Federation found 16% of its farmers surveyed had been in discussions with a solar leasing project in the past six months.

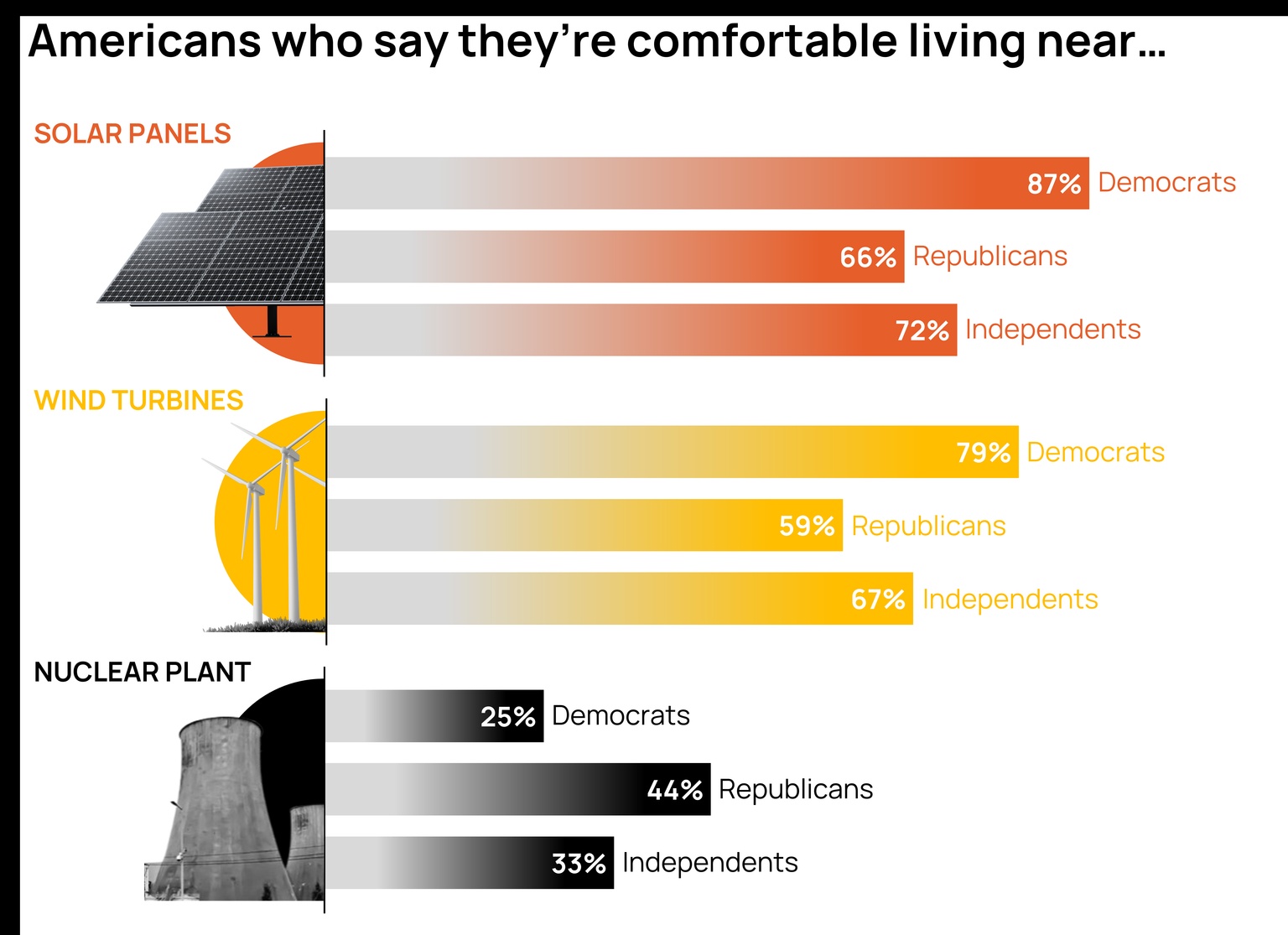

For what it’s worth, solar is less contentious than other clean power projects. According to a Washington Post-University of Maryland poll released in late 2023, both Democrats and Republicans are more comfortable living near a field of solar panels than either wind turbines or a nuclear station. That’s not unique to the US. Data from the UK found both wind and solar projects struggle to get local planning approval, with half of wind projects being rejected by locals and one-quarter for solar.

Washington Post-University of Maryland July 2023 Climate Poll

To get projects across the line, companies are increasingly turning to community benefit agreements to help secure the support of locals.

Other permits and agreements: There’s a range of other permits needed before a project can start construction. They include checks on environmental impact, and whether new projects will disturb historically or culturally important sites.

Environmental permits are often the trickiest and can be a pain even after they’ve been secured. Researchers found 38% of wind projects and two-thirds of solar projects built between 2010 and 2018 that completed environmental impact studies faced litigation.

It used to be that figuring out the economics of a solar project was a simple task. With an understanding of project costs and the amount of sunlight expected to shine down on the panels, it was straightforward to figure out the sale price of electricity needed to achieve a return. But higher levels of solar and wind have thrown a wrench into this process, too.

Clouded future: As more solar is added in a region, the first impact felt by the grid is the forming of a duck curve — midday solar power outcompetes other sources of electricity on price and pushes them out. The growing belly of the duck is a huge wedge of solar production in the middle of the day that forces other power plants to react, often by quickly ramping up or down.

As the wedge of solar grows and without enough transmission to move it all, solar eventually competes with itself locally, forcing some of the projects to be curtailed. Many will also earn tax credits for each unit of electricity they generate, leading to the phenomenon of negative pricing where projects will bid below zero because tax credits make the project whole.

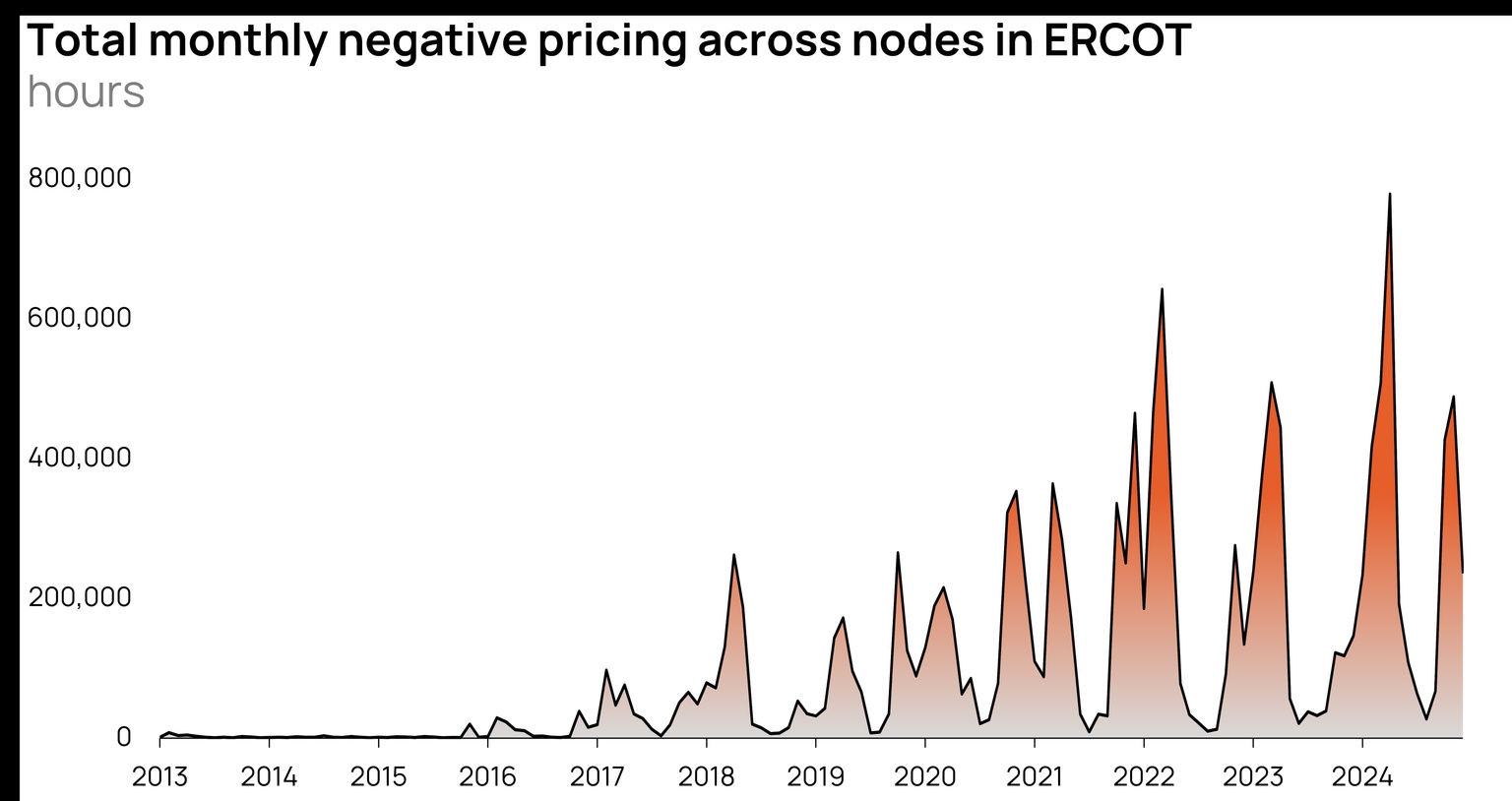

Negative pricing is becoming increasingly commonplace, particularly in Texas and California, two states with already abundant wind and solar generation.

Source: Orennia

All of this to say, between curtailed production and negative pricing, figuring out how to fill in the revenue line of the economic model for a new solar project now involves some degree of soothsaying. Project analysts might be dressed in Patagonia, but they’re modern-day Oracles of Delphi.

Future pressure: Speaking of fortune telling, it’s not hard to imagine a future where companies are more scrutinized for where they site their projects. West Texas is currently a hotbed where tech firms and hyperscalers are building solar and wind projects en masse, in part to collect renewable energy credits (RECs) that get put toward their claims of running on 100% renewable energy.

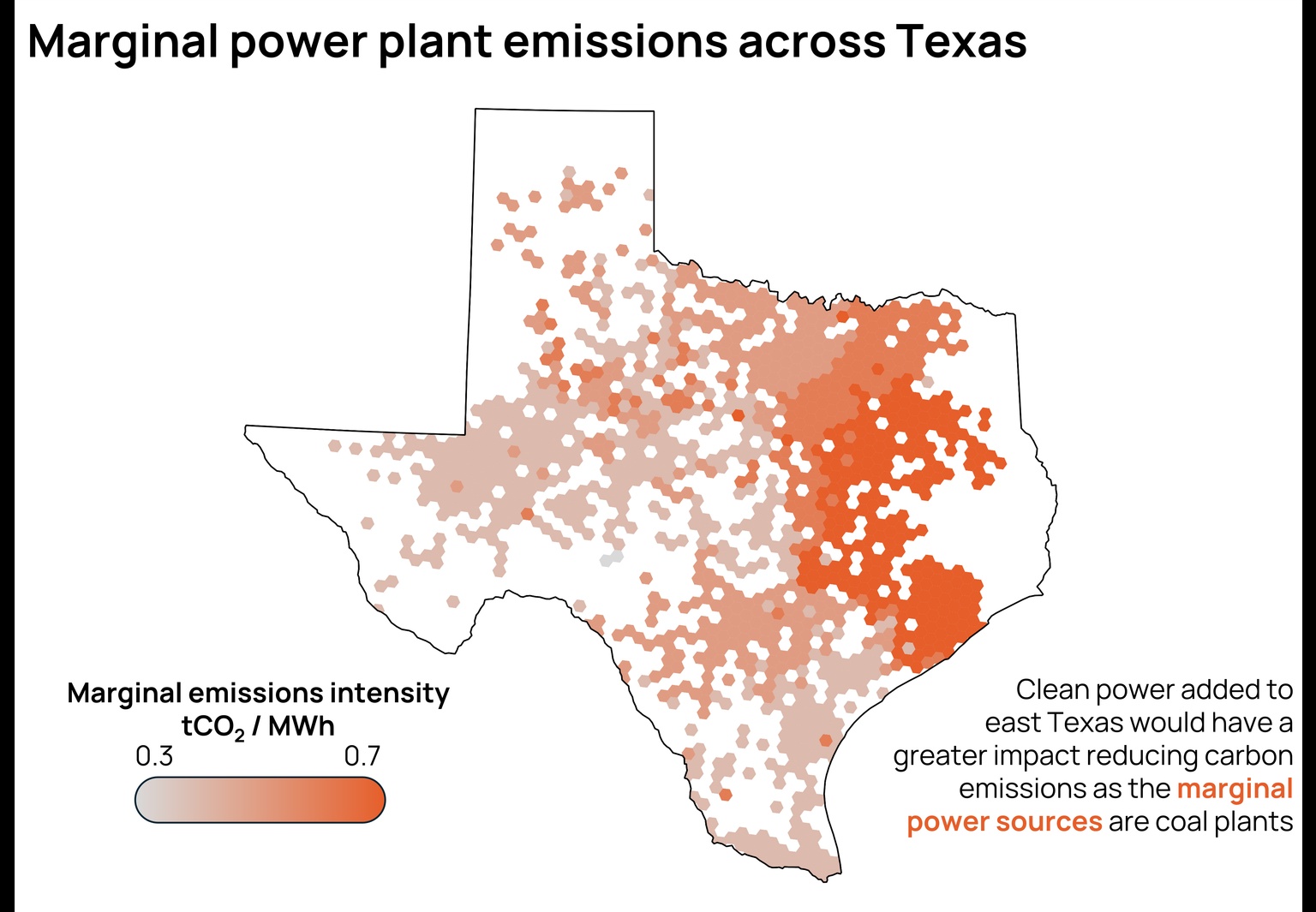

But as renewables increasingly curtail other renewables, the climate merits of new projects are questionable. Instead, by replacing credits for producing renewable electricity — which is how it's currently accounted for — with credits for offsetting carbon dioxide, companies can have more of a direct impact in reducing power sector emissions.

Source: Orennia

To do this requires an understanding of the local marginal emissions intensity – the projects that will be displaced by new, low-cost power added to the local grid. A new solar project will likely avoid more emissions in East Texas, with its abundance of coal power, than West Texas, where the supply is dominated by wind, solar and gas.

Installing solar power in the 2020s looks nothing like California’s Hesperia project of the early 1980s.

For building projects, it’s gotten easier. No longer the quaint interest of beloved presidents like Jimmy Carter, the solar industry now employs nearly 300,000 people in the United States. With it, a deep industrial knowing on how to get projects built has developed. And global supply chains and advanced manufacturing have since brought costs down 99%.

But for developers trying to site power projects today, between navigating the interconnection queue, curtailment, negative prices and project impacts, it’s a Daedalian maze.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.