Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

How will a weaker US dollar impact the energy industry?

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

In the middle of the Vietnam War, sitting in the Oval Office, President Richard Nixon faced an impossible decision: crash the American economy or break the global financial system.

The world at the time ran on the post-war global monetary system called Bretton Woods, which rested on a promise by the US that foreign governments could convert American dollars into gold at a set price of $35 per ounce. This provided stability to the US dollar in a world trying to put the pieces back together after World War II.

Foreign governments wanting to share in that stability pegged their own currencies to the US dollar, effectively pegging everything to gold. This led commodities like oil and minerals to be bought and sold in gold-pegged dollars, bringing further stability to the system.

But as both the Vietnam War and global rebuilding pressed on, so too did American printing presses, flooding the world with dollars to cover rising social and military costs. The world was approaching a point where demand for American dollars was more than physical gold could meet. The system would either drain the gold from Fort Knox, face widespread deflation or erode the value of the dollar. All would be disastrous.

President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office // PICRYL

Faced with a global financial system on the verge of collapse, Nixon faced a nightmare dilemma no president would ever want: jack up interest rates and crash the American economy or end the gold standard and break Bretton Woods.

The end of the golden years: Nixon had no choice but to ditch the gold standard, which he did in August 1971, ending the convertibility of dollars into gold along with the global financial system of the day.

Within about 18 months, the dollar lost nearly 20% of its value and the impacts rippled across the world. In the oil industry alone, exporters suddenly realized they were being paid in a currency losing its purchasing power—every barrel sold bought less in the real world. So, they jacked up rates, energy prices exploded, inflation surged and the modern era of resource geopolitics was born. Other global industries faced a similar reckoning.

A modern devaluation: Fast forward to today and the dollar is once again weakening.

Pressed by reporters last month about whether he was concerned with the devaluation of America’s currency, President Trump seemed unbothered. “No, I think it’s great, the value of the dollar… dollar’s doing great,” he said. This further sent the dollar plunging, gold skyrocketing, and made many realize that devaluing the dollar is a feature, not a bug, of this administration.

With fuels sold abroad, many power technologies manufactured overseas and a focus on consumer prices, how will a weaker US dollar impact the energy industry? Let’s wade in and find out.

An important but not-obvious first question is how do we even know the dollar is losing value?

When prices change, for most people the assumption is that it reflects a change in the value of the good, not the currency. If gas prices suddenly spike at the gas station, the thought is “wow, that must be because of what’s happening in Iran” or something, not “geez, I hope the dollar is OK.”

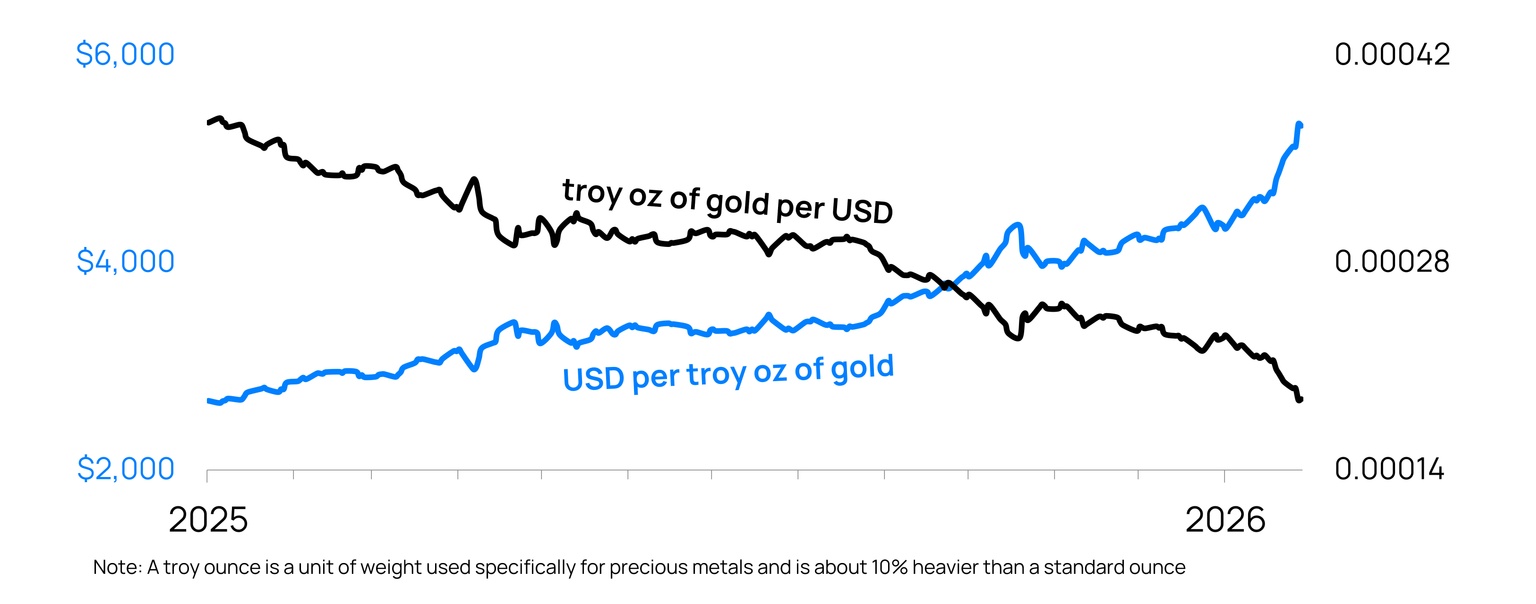

Gold recently hit $5,000 per ounce, and there are two ways to think about that: is gold now worth $5,000 an ounce or is one dollar now worth just 1/5,000th of an ounce?

Source: World Gold Council

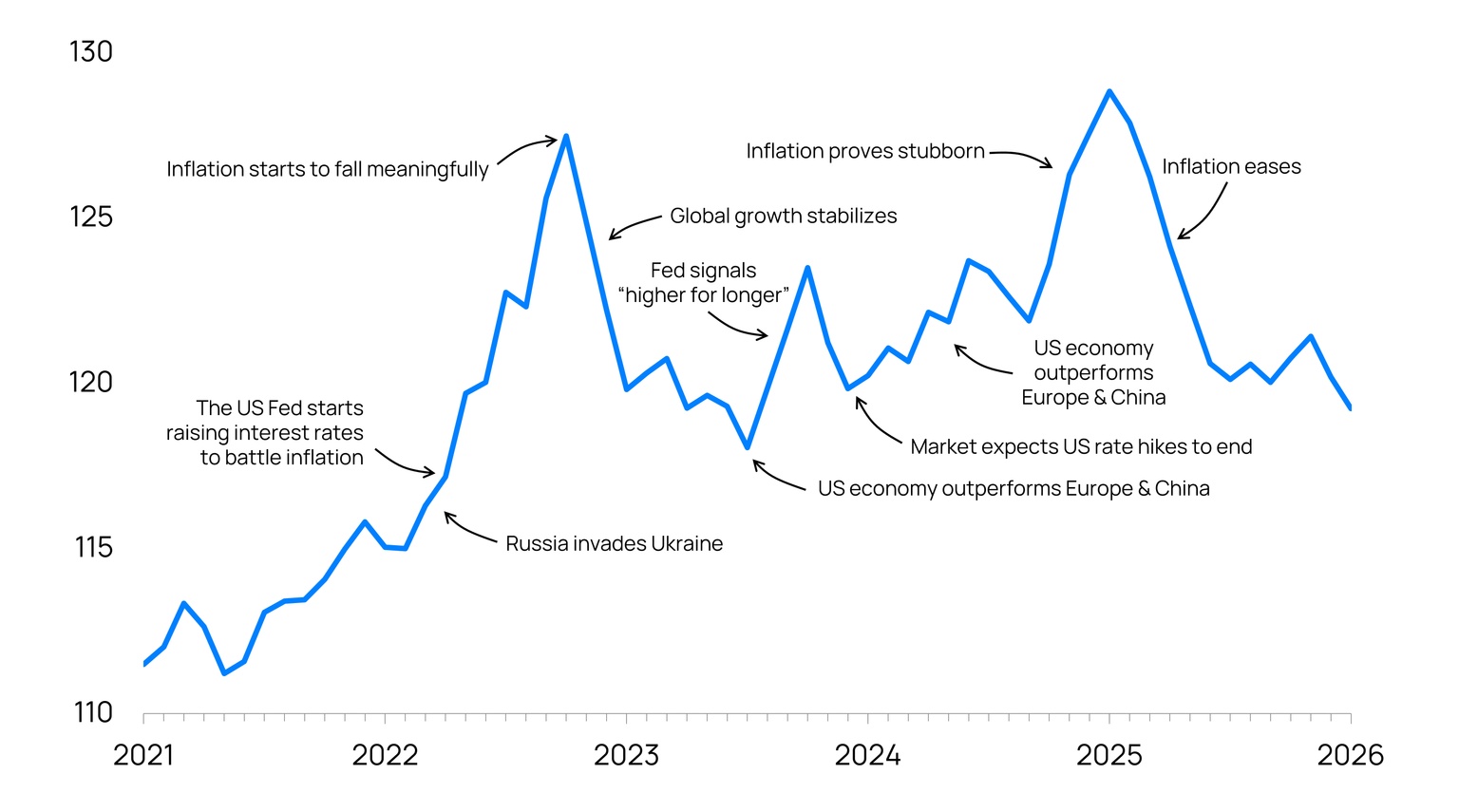

The official measure of the strength of the dollar is called the Broad Dollar Index (BDI), put together by the Fed. It’s the weighted average of the greenback against the currencies of a broad group of major American trading partners. In plain English, it measures whether the dollar is stronger or weaker than the currencies of countries the US does business with.

The recent fall: Using the Fed’s BDI, the dollar has lost 8% of its value since Trump took office for the second time, the fastest 12-month drop since the financial crisis in 2008.

To be clear, the drop wasn’t manufactured by the White House. The most common drivers of a weakening dollar include expected future interest rate cuts by the Fed, higher-than-usual inflation, heightened geopolitical tensions or large fiscal deficits. Check, check, check and check.

But the administration also isn’t trying to boost its value. The president could talk up the dollar but has instead been all-but cheering for its fall. The Fed could raise interest rates, the opposite of what the president is pressuring the central bank to do. And the US could look to rein in government spending or reduce tariffs, but these are so off-menu to the White House, they’re practically dietary restrictions.

Your role in the world will shape how you think about a depreciated dollar.

For those who make things: A weak dollar is great news for US manufacturers. It makes American assets cheaper in foreign currencies, which should lead to more investment from abroad. The goods produced by American factories become more affordable for foreign buyers. And it makes purchasing foreign goods more expensive, further stoking investment at home.

Source: Federal Reserve

This was articulated by Chairman of US Council of Economic Advisers and Fed Governor Stephen Miran in his how-to paper on restructuring the global financial system. “From a trade perspective, the dollar is persistently overvalued, in large part because dollar assets function as the world’s reserve currency. This overvaluation has weighed heavily on the American manufacturing sector while benefiting financialized sectors of the economy in manners that benefit wealthy Americans,” said Miran.

Or, as the president put it more succinctly last July: “It doesn't sound good, but you make a hell of a lot more money with a weaker dollar... than you do with a strong dollar.”

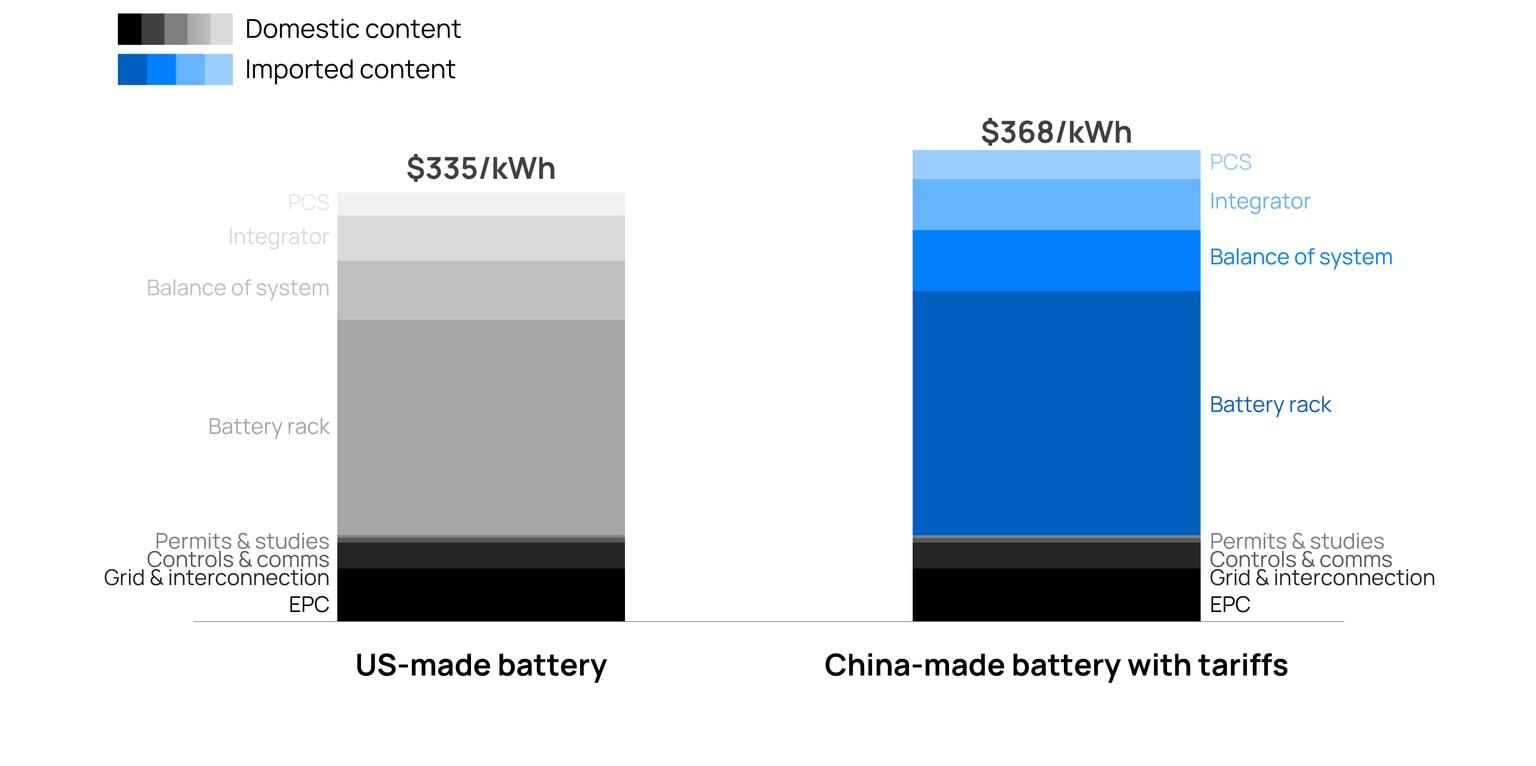

For those who import things: A weak dollar is certainly not ideal for businesses that rely heavily on components sourced internationally, especially industries that are capex heavy, like renewables and batteries.

The American wind sector is highly sensitive to movements in the dollar because so much of the equipment is from abroad. The industry has been working to domesticate its supply chains, but in 2024, more than two-thirds of turbines blades used in the US came from either Mexico or Canada.

In solar, despite significant incentives to bolster domestic production, the US still imported 54.3 gigawatts worth of finished solar modules in 2024, more than 80% of which came from either Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia or Cambodia. Then, last April, worried Chinese panel makers were just setting up shop in Southeast Asia, the Commerce Department hit solar panels and components from all four countries with tariffs. A weaker dollar might as well be another tariff.

And if the dollar sneezes, battery projects catch the flu: 84% of US energy-storage batteries are imported, and foreign components make up over 80% of total system costs for China-sourced units. A weaker dollar leads to higher foreign battery prices.

Source: Orennia

Put together, a weaker dollar will make it more expensive to build what are currently the cheapest sources of new power available and the only technologies that can be scaled quickly to address the looming power supply gap for data centers.

And for those who vote: The White House wants lower energy prices, Trump ran on a platform to lower energy prices, but a weaker dollar pulls in the opposite direction.

Oil and the dollar typically move in opposite directions. When the USD gets weaker, oil gets cheaper for everyone else, increasing its demand globally and sending prices up. It usually takes a few months, but it eventually translates to higher gasoline prices back home.

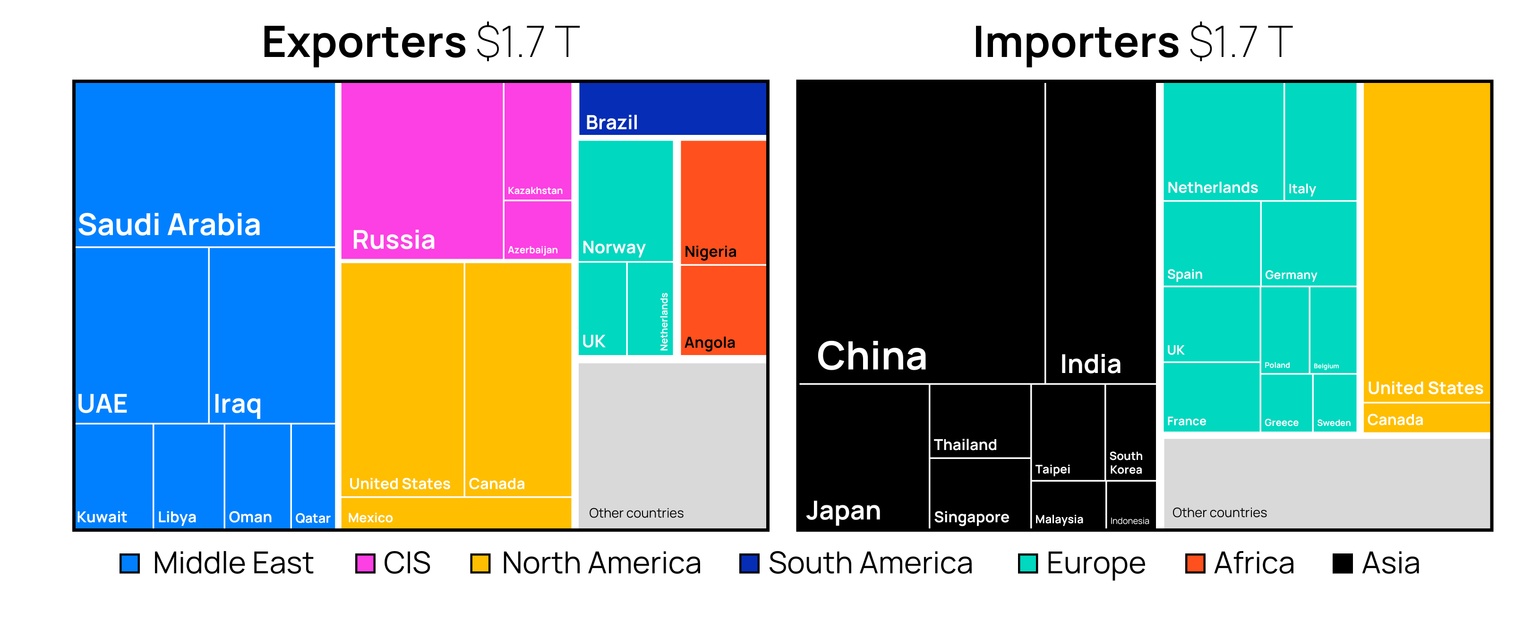

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity

The same is true for natural gas, where demand for LNG jumps when the dollar is cheap, draining domestic supplies and fomenting higher prices. This will be particularly acute for families, as natural gas accounts for more than 40% of the energy consumption for your typical US resident and nearly half of US home heating systems.

As for electricity, beyond the higher cost to build renewables and batteries, higher gas prices mean the gas plants that typically set the market price of electricity will need to charge more to recoup their increased fuel costs. It’ll be the buyers who will ultimately pay for that.

Taken together, a weaker US dollar will almost certainly raise energy prices for consumers. A tough barrel to look down with midterm elections just around the corner.

When Nixon ended the gold standard, the market discovered the greenback was overvalued and was forced to reset, instantly reeling over the loss of a strong US dollar. Unlike Nixon, Trump sees a weakening dollar as a step in the right direction for the economy, hoping to revive American exports.

If the dollar continues to lose value at the pace it has since the 47th president took office last January, the fall will be in line with its collapse at the end of the gold standard.

And like countries distancing themselves from the dollar after the end of the gold standard, governments today are quickly selling away their USD. Most notably China. An ominous sign of what’s to come for American diplomacy. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio told a crowd last week: “The time of the American dollar is done and in five years, we won't have the ability to sanction.”

As for American energy: A strong USD has quietly been subsidizing imports of solar panels, batteries and turbines to critical minerals to make energy prices more affordable.

When artificial price anchors break, reality sends the invoice.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.