Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Building at scale has always required more than ambition — it requires access.

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

On a clear spring day in the Utah desert in 1869, a congregation of workers, business leaders and politicians assembled around a railroad track to watch history unfold. Leland Stanford, the president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California, tapped a custom-made golden spike made of 17.6-carat gold into the ground at Promontory Summit. The symbolic spiking was to celebrate the completion of one of the most audacious undertakings in American history: the first transcontinental railroad.

A world changed: The next day, a freight train carrying Japanese tea left California destined for New York along the new rail line. Such shipments no longer needed to travel south by ocean, cross over Panama by land, and travel back north again by ocean. The six-month journey from San Francisco to New York was cut to just six days.

The ceremonial golden spike at Promontory Summit // PICRYL

Rail transformed America. Within 10 years of the golden spike, $50 million worth of goods were being shipped coast to coast across the rail every year, shrinking the country. The wheat farms of the Midwest were connected to the trading hubs of Chicago, while the silver mines of Nevada were connected to global markets via ports on the West Coast. By 1900, the US had roughly 193,000 miles of track completed, enough to crisscross the country more than 60 times.

Not everyone benefited: The rails were seen as an instrument of civilization, and so the government seized millions of acres of Native American land to grant to railroad companies.

Facilitated access to the West led American hunters to decimate the buffalo, vital to the traditional ways of the Indigenous Peoples. Bison populations fell from the tens of million in the early 19th century to near extinction, deepening Native American dependance on the government.

Nation building vs. land rights: The tension between national expansion and personal property has always been taut. The influential philosopher John Locke wrote that “life, liberty and property” were natural human rights, which Thomas Jefferson adapted to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence.

Governments seizing land for national infrastructure is still commonplace. The legal power is called “eminent domain” and is used extensively for things like highways, roads and bridges. But there are now increasing calls for eminent domain to be used more regularly to accelerate energy development.

The energy transition demands an unprecedented build-out of infrastructure — transmission lines, hydrogen pipelines, storage hubs, and interconnects. And while used infrequently for electrical generation projects, hydropower may be the exception, with large swaths of land needed to flood behind the dam.

Texas Comptroller

So, should governments go full Abraham Lincoln and force important nation-building infrastructure through or were John Locke and his property rights onto something? Let’s dig in.

Eminent domain has always been both controversial and essential to progress.

The legalese: As the US Justice Department put it, eminent domain applies to “every independent government. It requires no constitutional recognition; it is an attribute of sovereignty.” In other words, the law views being able to seize land for public good as a nation’s right, though landowners are usually given some protections.

In the US, private property is enshrined in the Fifth Amendment: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” The government can still seize land, but the owner must be paid fairly.

Unlike the US, the Canadian Constitution does not include private property rights, nor are they mentioned in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Instead, eminent domain falls under the federal and provincial laws known as Expropriation Acts that require landowners to receive fair compensation for property taken. While less enshrined, eminent domain is viewed as being more generous in Canada, covering additional landowner costs, like legal fees and land disturbance costs.

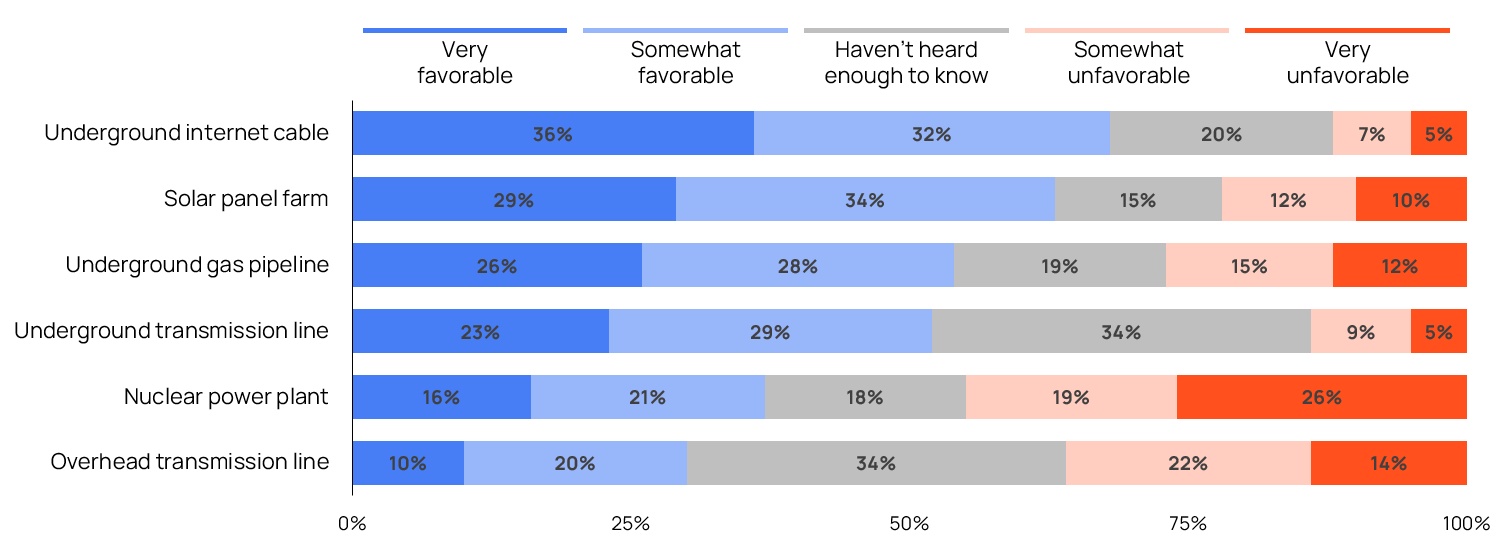

Data for Progress, 2024 survey

But in today’s competitive world, things are graded on a curve. Let’s go east to China.

Chinese land is considered dual use — one part “collective,” one part “state,” and 100% guaranteed to confuse foreign investors. Urban land is owned by the government while rural land is collectively owned by village communities. And similar to the US, property rights are constitutional.

The 1982 Chinese Constitution says, “the state may in the public interest take over land for its use in accordance with the law.” Though, as a legal scholar Mingde Ju wrote, “in reality, these legal rules are either ignored or relaxed.”

Given the restrictive nature of Chinese data, it’s tough to fully compare apples-to-apples but the anecdotes are there: building infrastructure and large energy projects is much easier in China.

Red advantage: The centralized ownership of land in China allows the government to dictate land for infrastructure projects without the need for prolonged negotiations with private landowners and with limited pushback.

In China’s 14th five-year plan, unveiled in March 2021, the government announced the Baihetan-Zhejiang high-voltage transmission project to move hydropower from the interior to the industrial heartland in the east. Construction of the 8-gigawatt, 2,140-kilometer transmission line started in October 2021 and was built and fully operational just over a year later, a speed that makes Ty Pennington look like an everyday DIYer.

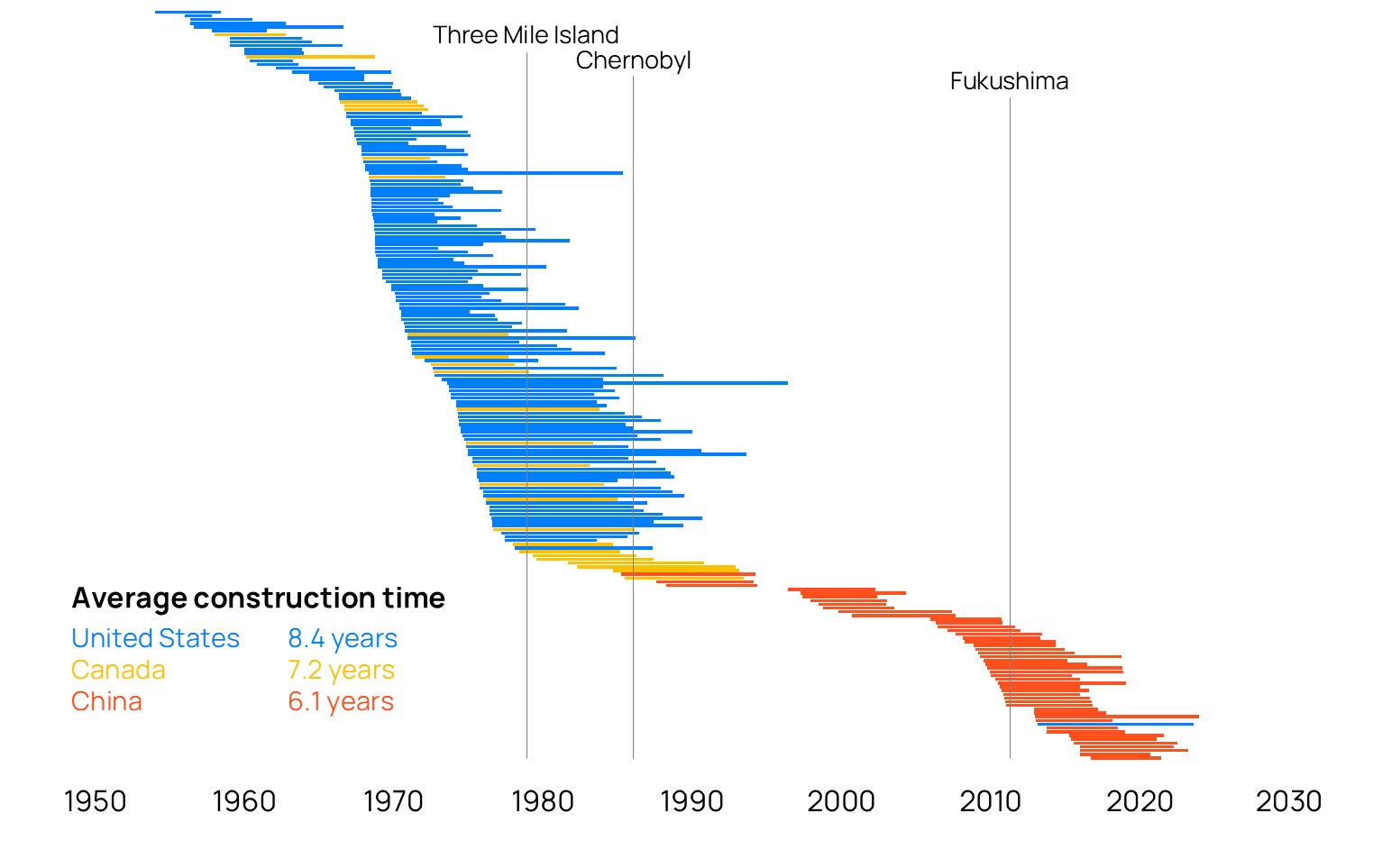

Global Energy Monitor

Now compare that to the 3-gigawatt, 550-mile SunZia transmission project in New Mexico. While first started in 2008 and approved in 2015, environmentalists opposed the project’s proposed route so successfully, it was stalled in the courts in 2018 and the company was forced to reapply. Pattern Energy later bought the rights, submitted SunZia’s updated application and the project is expected to come online later this year.

One-third the size and a quarter the length but will ultimately take 10 times as long to build as the Baihetan-Zhejiang line. While the US moves fast and breaks things, China moves fast and actually builds things.

Green tape, red lights: It’s not just the land acquisition process that is slowing down development. There’s a sad irony that some of the greatest barriers to building the energy and infrastructure projects needed to protect the environment are environmental studies.

Researchers from Utah’s Center for Growth and Opportunity found clean energy projects across the US take an average of three years to complete the EPA’s environmental impact study process. And the related report tops usually 1,200 pages. For many projects, it can be worse.

Northwest Energy spent three years and nearly $3 million studying the impact a large wind farm project in Washington would have on an endangered bird called the marbled murrelet. Environmentalists kicked up a storm over concerns for the local bird, yet researchers found the project’s turbines were likely to kill just one bird every other year. Nonetheless, due to rising costs and related delays, Northwest cancelled the project.

(For the record, the number one mass murderer of birds in the US is the domestic house cat, responsible for killing up to four billion birds annually, roughly 10,000 times more than wind turbines. Naughty kitties.)

The West faces some uncomfortable decisions.

As the old adage goes, the greatest trick authoritarian governments ever pulled was forcing its opponents to play by its rules. If western nations want to keep pace with China, many of the well-intentioned regulations and processes that have been developed over the years will either need to be undone or at least significantly altered to both keep pace with China, which has nearly limitless access to electrons, and to achieve timely climate goals.

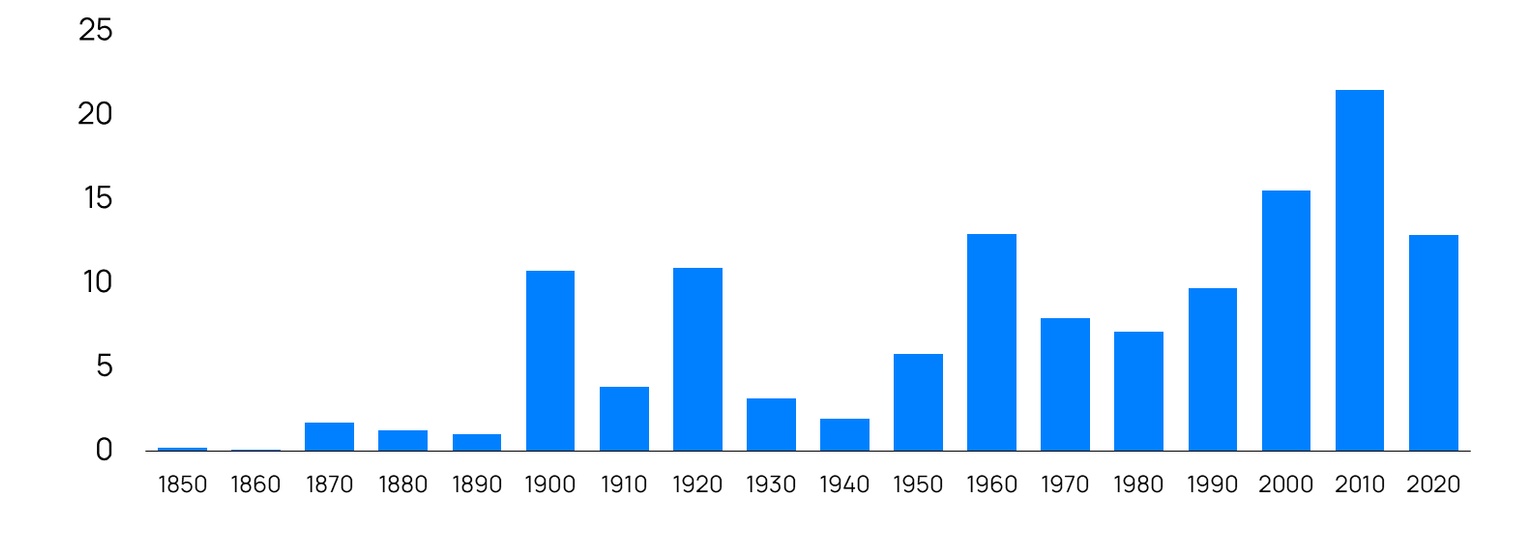

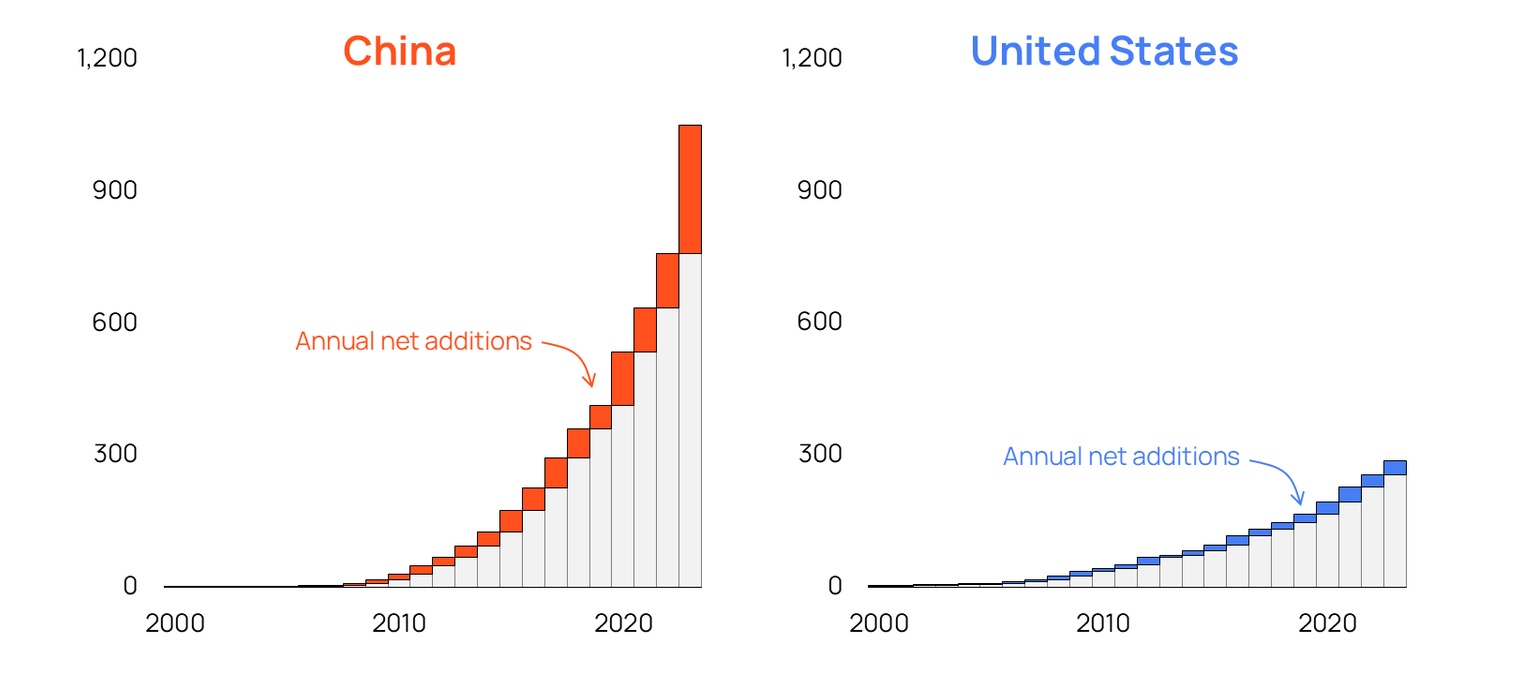

Energy Institute, Statistical Review of World Energy 2024

The US Department of Energy study on national transmission needs found with moderately high new power demand, regional power lines will need to grow by two-thirds by 2025, and more than double if load growth is higher. Yet, building transmission lines has come to a crawl with just over 200 miles of new high-voltage lines built in the US last year, roughly the distance between New York and DC.

And three major Midwest carbon pipeline systems — the Midwest Carbon Express, Heartland Greenway and the Wolf Carbon Solutions pipeline — failed to secure land rights or eminent domain use. Two of the projects have since been cancelled and the Midwest Carbon Express is on shaky ground. Together, the trio of pipelines would have helped in sequestering or using up to 45 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from ethanol plants.

State or federal: Which government holds eminent domain powers depends on the project type. In the US, power is held federally for projects like natural gas pipelines, falling under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The Mountain Valley Pipeline and the Penn East Pipeline, two controversial American pipeline projects, were both granted eminent domain in their process to get built.

But for transmission and carbon pipelines, authority lies with each state. This poses a problem for projects looking to simply pass across a state as developers must prove projects serve a public purpose. Even if a development serves a national good, it can be rejected for not benefiting every state along the way.

And unfortunately, local governments have proven to be better at stymieing energy projects than endangered murrelets.

The West doesn’t lack engineers, capital or land. It lacks permission.

While using eminent domain to build the transnational railroads was a positive for the North American economy, it was no doubt a negative for the Indigenous way of being. But it’s not as black and white as nation building versus land rights — a lot has been learned in the 160 years since the golden spike was struck in Promontory.

Pre-approved energy corridors, like those being proposed by candidates in the current Canadian election, could turbocharge project approvals. As could streamlined approval processes. Even Enbridge’s equity partnership with 23 Indigenous communities was a creative way to get seven pipelines across the line and get them built without resorting to the courts.

Bottom line: Eminent domain is a tool in the toolbox, and one of last resort, but it might be time to start sharpening it.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.