Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Find out what really happened with the Decatur CCUS project

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

In many ways, the city of Decatur, Illinois, still feels like small town America. Despite a population of more than 70,000, the city’s soul is still connected to the agriculture that surrounds it. This year will mark the 169th Macon County Fair, its annual event filled with livestock competitions, live music and a carnival.

At the center of the city, the Historic District is a reminder of the prosperity the municipality has enjoyed for more than a century. Decatur has been a key logistical center in the Midwest, being situated along several railways since the late 1800s. And at the center of the Prairie State, Decatur earned the nickname the “Soybean Capital of the World” for its role in driving the production and adoption of soybeans.

Credit: I Like Illinois

Due to it being located strategically at the heart of the US agriculture belt and for its connection to major rail and transportation routes, Decatur was chosen to be the headquarters of the food and processing giant Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) in the 1960s. Even today, despite moving its headquarters to Chicago, ADM is still one of the city’s largest employers with over 4,000 Decaturites working for the company.

Bushel and a peck: One of ADM’s cornerstone facilities in the city is its 350 million gallon per year corn ethanol facility, which emits over one million tons of carbon dioxide per year.

Because of the fermentation process needed to make the alcohol from corn, ethanol facilities produce carbon dioxide with a remarkably high purity. The fermentation stream is usually 99% carbon dioxide, with just trace amounts of water, sulfur and other organic compounds, making it an ideal candidate for carbon capture. This was not lost on the US Department of Energy (DOE).

The saying “knee-high by the Fourth of July” is an idiomatic expression about how tall corn should be by midsummer to gauge its growth progress. It’s a midpoint that tells you something about how its endpoint will look.

Carbon capture technology is at a similar point: growing up and getting ready for decarbonization primetime. One of the steps in a technology’s progress is a bona fide commercial-scale project. ADM built one of the first in North America, the Illinois Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage (ICCS) project.

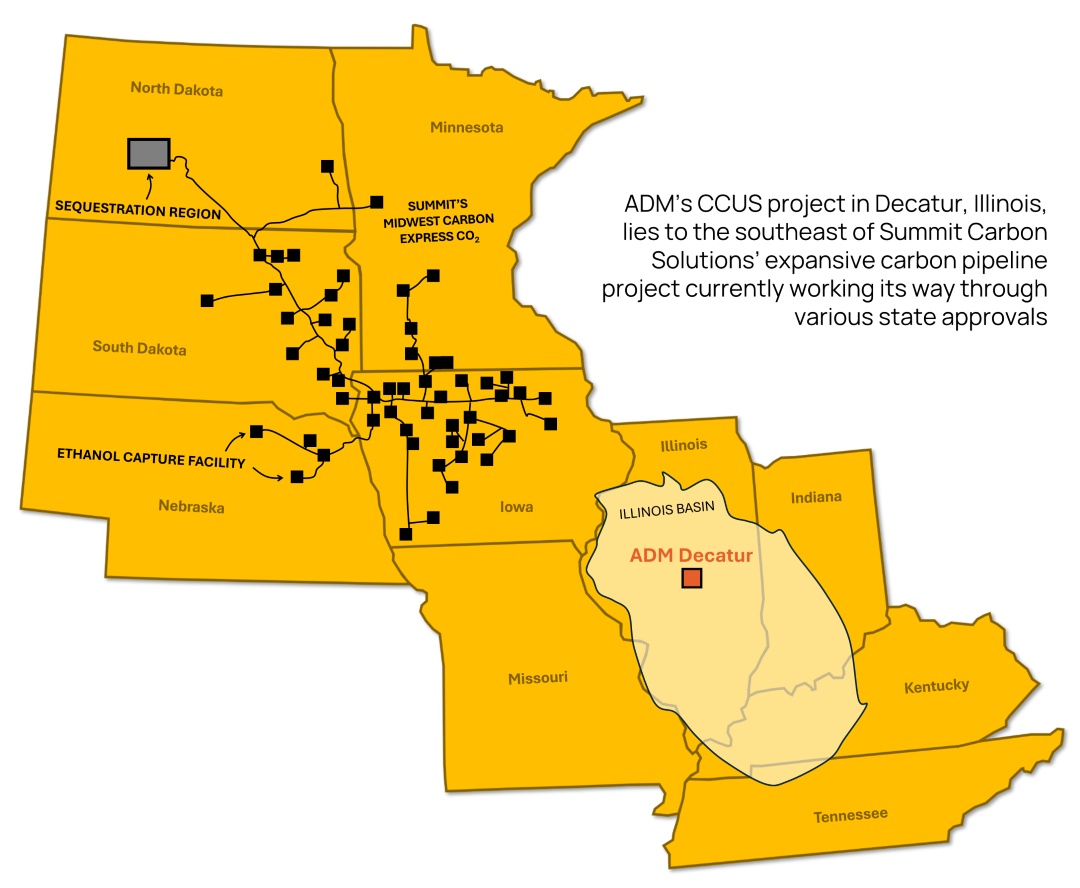

Decatur: Ahead of the ICCS commercial project, ADM partnered with the DOE and the Illinois State Geological Survey for a demonstration project. The Illinois Basin Decatur Project (IBDP) showed — successfully — the feasibility of storing carbon dioxide in the local subsurface.

Following the demonstration project, ADM and the DOE moved to the commercial project, designed with the ability to store 1.1 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. The ICCS was not only designed to be a commercial-scale project, it was also billed to demonstrate the commercial-scale applicability of carbon capture technology. There were a lot of eyes on this project.

It should then come as no surprise that a media frenzy erupted when the public became aware ADM had discovered carbon dioxide in a geological zone that should have been without. There was understandable public fret over the environmental and technological consequences of the event.

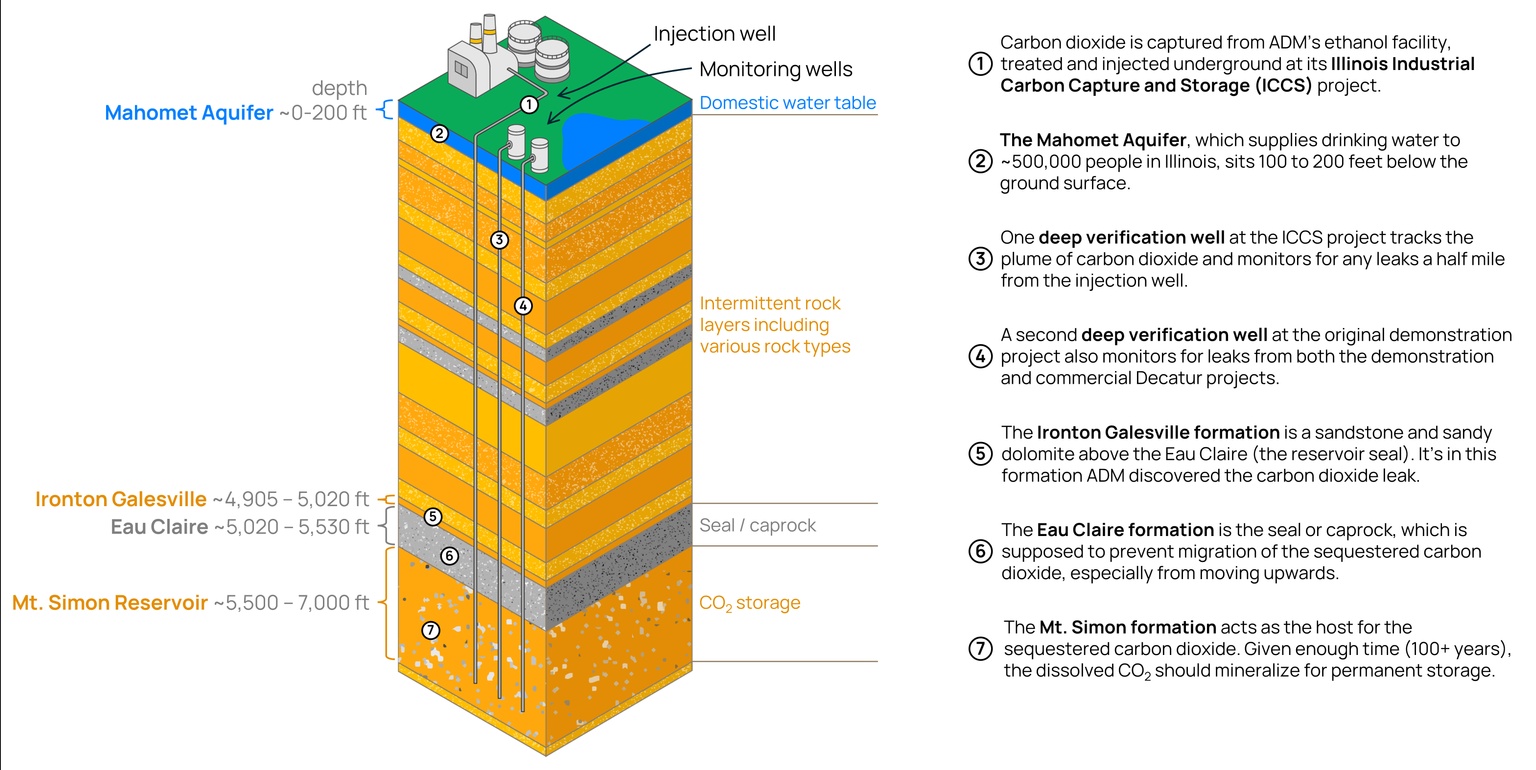

On top of whether it proved conclusively that carbon capture is a technology to avoid, there was the more immediate concern that the leak would contaminate the local Mahomet Aquifer, which supplies drinking water to over 500,000 people in 14 Illinois counties.

The blowback: The co-director of Eco-Justic Collaborative warned “this leak is a wake-up call. It’s a stark reminder that carbon capture is not the climate solution it’s sold as, but a dangerous gamble with our drinking water.” Food & Water Watch had similar thoughts, saying, "this incident puts an exclamation point on concerns communities across the country have been raising for years about the dangers the CCS industry poses to public safety and drinking water.” And Environment America wrote the project “could be leaking highly corrosive liquid carbon into the local drinking water supply.”

Enter the EPA: ADM also reported to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that it had discovered a second leak, this one at the demonstration project, leading the company to pause injecting at the commercial site for investigation. The EPA came out and accused the company for violating safe drinking water rules.

Yet, despite all the headlines, ADM said there is “no threat to public health.”

Which all begs the question: what actually happened at Decatur and what does it mean for carbon capture as a long-term solution?

Before diving into the technical details of the Decatur incident, it’s worth considering what would be, using the parlance of today, a red flag versus just a beige flag for carbon capture?

Differentiating: Red flags are fundamental flaws that could prevent carbon capture from ever being a viable or safe technology, while beige flags would be issues that could be resolved with engineering and design.

Modified from ADM’s project diagram

For carbon capture, the most pressing concerns surround whether carbon dioxide can be kept underground for extended periods of time. Simply put, will the storage reservoirs and caprock seals work as predicted and prevent sequestered carbon dioxide from migrating back to the surface?

The evidence never lies: The series of events that led to the ICCS leak can be parsed together with public data released by both the EPA and ADM, with some help from POLITICO and some environmental NGOs.

With that, let’s Gil Grissom this crime scene and figure out exactly what happened.

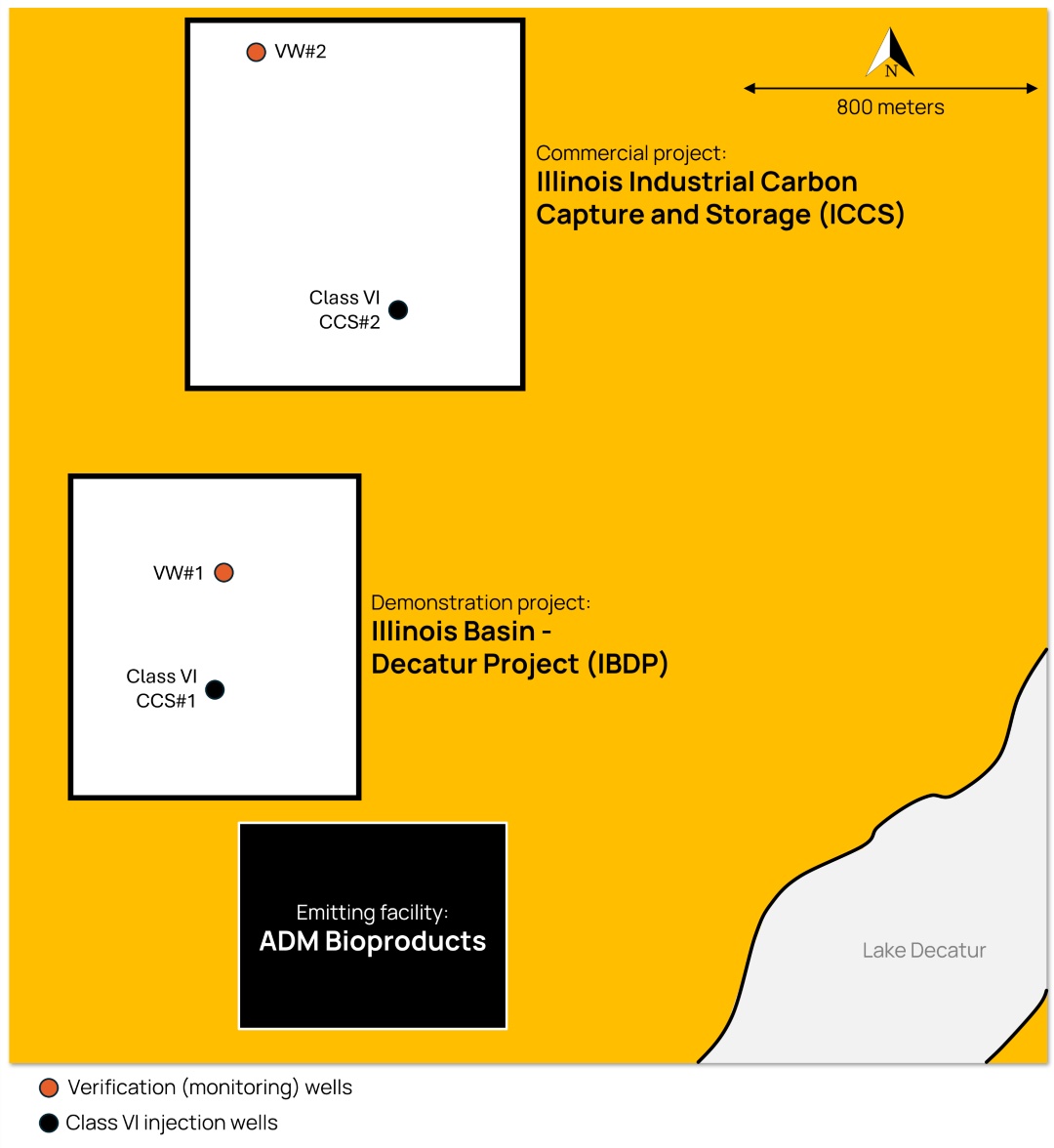

To get our mind’s eye on this project, all the wells and facilities involved are roughly within a mile and a half of one another.

The facilities: At the very south is ADM’s biofuel facility, the source of carbon emissions that are to be captured and sequestered. Just across the street is the IBDP demonstration project and to the north of that is the commercial-scale ICCS project.

The wells: The demonstration and commercial projects each have a Class VI well and a deep monitoring verification well. The Class VI wells are used to inject carbon dioxide into the subsurface, though injecting had finished at the demonstration years ago. The verification wells used to monitor the sequestered carbon dioxide were drilled into the storage reservoirs, and both are still actively monitoring.

With the scene set, let’s piece together the series of events that led to the leak.

2017: Sequestration at ADM’s ICCS project begins at an industrial scale of up to one million tons of carbon dioxide per year.

September 2020: A gauge in one of the deep monitoring wells (VW#2), just a few hundred meters from the injecting well (CCS#2), started having intermittent electrical problems.

January 2022: At this point, all the gauges in VW#2 were malfunctioning regularly.

March 2023: ADM first detects corrosion at VW#2.

October 2023: After the company failed to pull out and recover the monitoring tools from the VW#2 well, ADM moved to plug the well.

February 2024: ADM meets with the EPA to discuss the issues known at the time.

March 2024: Fluid is discovered in the Ironton Galesville geological formation by VW#2 from company testing. The Ironton Galesville sits right above the Eau Claire, which acts as the seal or caprock for the storage reservoir.

June 2024: The EPA sent an email — later obtained and reported on by POLITICO — to companies applying for carbon injection wells relaying that pipes made from steel type 13 Chrome are not suitable injection wells, as they corrode in the presence of carbon dioxide and water.

July 2024: Following testing, ADM confirms that carbon dioxide was part of the fluid in the Ironton Galesville, the result of the monitoring well’s previous corrosion. Findings are reported to the EPA.

September 2024: The EPA issues a proposed enforcement order to ADM for violating the Safe Drinking Water Act, ordering the company to take action to ensure the safe operations of the project. The environmental agency assures it does not believe there is any threat to drinking water in the area.

September 2024: A second leak is discovered above the monitoring well VM#1 in the demonstration project, this one a brine — subsurface salty water. Carbon dioxide is not believed to be part of the fluid. An ADM spokesperson estimates the original leak to be around 8,000 metric tons of liquid carbon dioxide and other fluids.

October 2024: ADM pauses injection at the ICCS project to investigate the leaks.

November 2024: After further tests, ADM revises downward its view on the scale of the carbon dioxide leak in VM#2 to between 2,670 and 3,940 metric tons.

Having dug through the technical reports, public statements made by both ADM and the EPA plus various emails published by groups like POLITICO, the source of the problem is clear: it’s not just that the monitoring wells caught the leak, they caused the leak.

Digging deeper: There are two issues at the heart of this incident.

The first, like a needle poking into the top of a balloon, the monitoring well used to identify carbon dioxide migration was drilled and placed into the containment reservoir. ADM has since updated its monitoring well policies to measure only above and below the confining zone and to use separate wells, limiting the chance of a repeat event.

Second is materials science. It seems likely, based off the email leaked by POLITICO, that a core lesson the EPA took from Decatur is that future CCUS projects in the country should avoid the use of 13 Chrome steel. Engineers will have to figure out what materials are needed that aren’t corroded by carbon dioxide and the carbonic acid that forms when carbon dioxide and water meet underground.

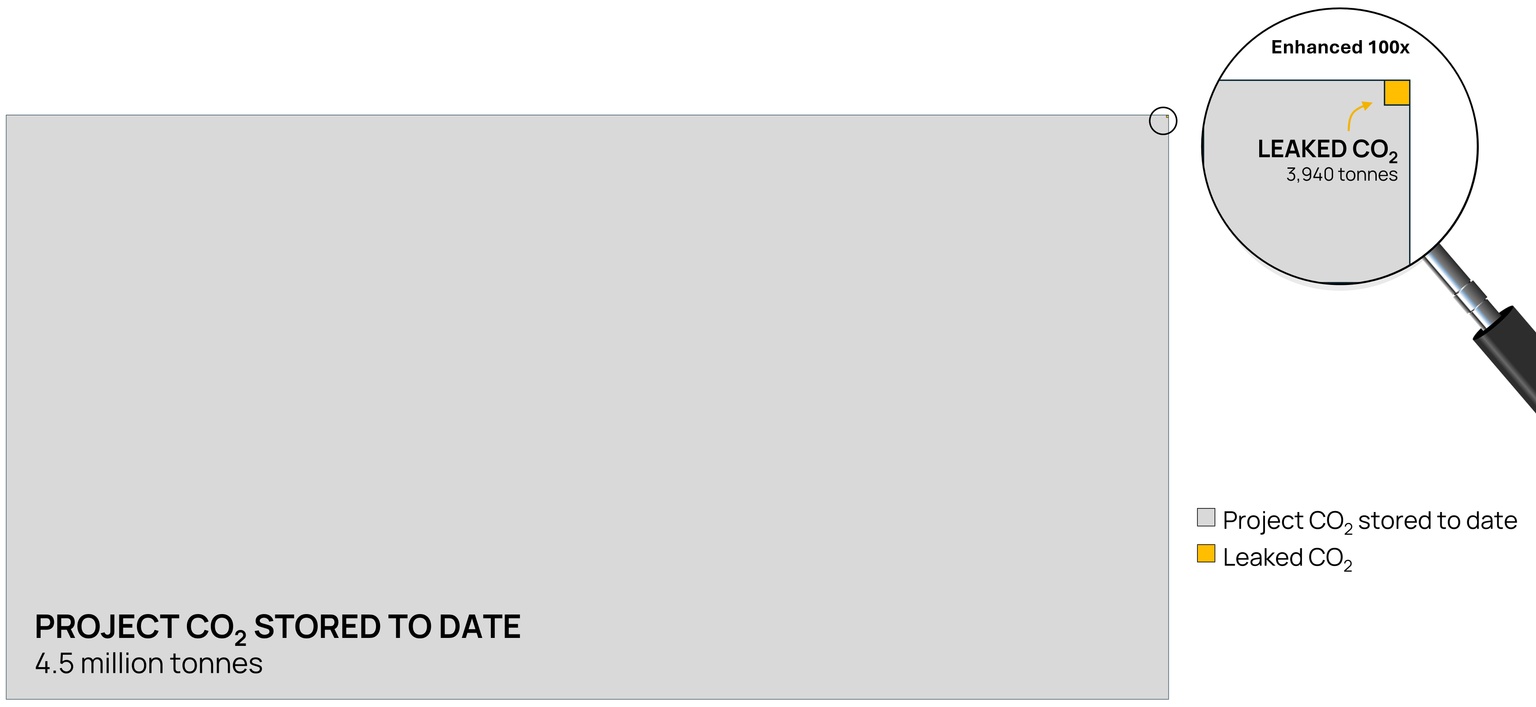

Scale and impact: It should be noted, very little carbon dioxide was leaked, and what was didn’t move very far. At the upper end of ADM’s estimates, ~4,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide leaked into the Ironton Galesville, roughly 0.09% of the project total to date and equivalent to the annual emissions of about 870 cars.

And those volumes will almost certainly never make it anywhere near local drinking water. There is more than a mile of rock between where the leaked carbon dioxide has settled and the nearest aquifer. Testing has shown the plume to have settled just above the seal.

The dissolved carbon dioxide will eventually — hundreds of years from now — mineralize and be permanently stored underground.

There were some important lessons learned from ADM’s Decatur leak.

The right ingredients: Like many nascent technologies, materials are part of the discovery process. The blades of large wind turbines failed until stronger composite materials were used that could withstand the greater torques. Light-water nuclear reactors initially struggled with parts corroding in the challenging operating conditions, leading to better practices and materials used in their designs.

13 Chrome steel looks like it’s on the way out for metals used in the subsurface wells of carbon sequestration projects, but alternatives will be brought forward that are better fit for purpose.

Better well placement: Turns out, the fewer wells punctured into a reservoir meant to store gas long term the better. Luckily, regulations require monitoring above and below the storage reservoir, not inside of it.

Future verification wells, including their instrumentation, can be placed away from the subsurface storage formation and protect the integrity of the sealed reservoir.

Monitoring works: While the placement and materials of the monitoring well likely caused a leak, the monitoring system worked as it should. The instruments detected, ADM reported, the EPA responded and actions were taken to contain the issue.

Put simply, the media reaction was an overreaction.

The issues that appeared were beige flags that can be addressed with engineering and design, not red flags that derail the technology’s potential. That’s not to say those won’t appear in the future. And carbon capture projects seem to receive extra scrutiny from the public compared to other clean technologies, so operators and agencies should take some learnings on how and when to communicate with the public to avoid a similar blowup.

But if there’s any silver lining from the events at Decatur, it’s these lessons can be absorbed and applied to future projects, moving carbon capture one step closer to its decarbonization primetime.

As Gil Grissom put it about continuous improvement: “What we are never changes, who we are never stops changing.”

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.