Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

How will China hit their peak carbon emissions well before 2030?

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

In an effort to transform late-1950s China from being a rural and agrarian society to a global industrial powerhouse, Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong launched a national campaign known as the Great Leap Forward. Through the use of people’s communes, China would boost its output of both agriculture and industry, with a focus on grain and steel.

Smelted dreams: No one can knock Chairman Mao for a lack of ambition: The communist leader set a goal for the country to become the world’s largest producer of steel, looking to surpass English production levels in 15 years and American steelmaking in 50. The idea became so popular, many children born in 1958 and 1959 were given the names Chaoying (“Surpass England”) or Chaomei (“Overtake America”).

As part of the great steel push, communes were coaxed into constructing small-scale blast furnaces using local materials, including mud, wood and even hair. The locals melted down everything from old farming tools to utensils and woks in an effort to produce low-cost steel for the nation. These have gone down in history as the “backyard furnaces” and went exactly as well as you might expect rural peasants building and operating their own blast furnaces would have. A disaster.

An artisanal blast furnace for steelmaking, now referred to as a ‘backyard furnace’ // Wikipedia Commons

For one, the process ended up being costly. The steelmaking was so inefficient, it cost twice as much to produce as industrial steel, despite the cheap labor. And the final product was low-quality brittle pig iron or slag — functionally useless and secretly thrown out, but counted for quotas nonetheless, to not ruffle the feathers of Chairman Mao.

Unfortunately, production costs went beyond the monetary. Feeding the inefficient backyard furnaces consumed so much wood, 10% of China’s forests were cut down to keep the hearths burning. And when local forests ran out of fuel, peasants turned to burning their doors and furniture.

Things went from bad to worse as the agricultural revolution yielded similar results as the industrial one, leading to a mass starvation that killed between 15 and 55 million people.

Lingering impact: The entire Great Leap Forward episode, which only lasted four years, helped cement many westerners’ views of China as a poor, rural and environmentally damaging nation. But fast-forward 70 years and China is now a very different place, urbanized and the preeminent industrial nation of the world.

In 1993, the Asian superpower surpassed English steel output and just four years later overtook the US. China now accounts for more than half of all steel production around the world.

Around the time of the 2008 financial crisis, China eclipsed the US as the world’s top emitter of greenhouse gases, further engraining its reputation as being hard on the environment. Since them, China has added annual emissions roughly the scale of the entire United States.

But many now are now speculating that China’s emissions have now peaked.

Source: Global Carbon Budget (2024)

In a survey conducted by climate thinktank Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CRECA), 44% of experts said they believe China’s carbon emissions will hit their zenith either this year or already have, which would be well before the country’s goal of achieving “peak carbon” emissions by 2030.

So, how did the world’s factory do it? Let’s fire up the backyard furnace and find out.

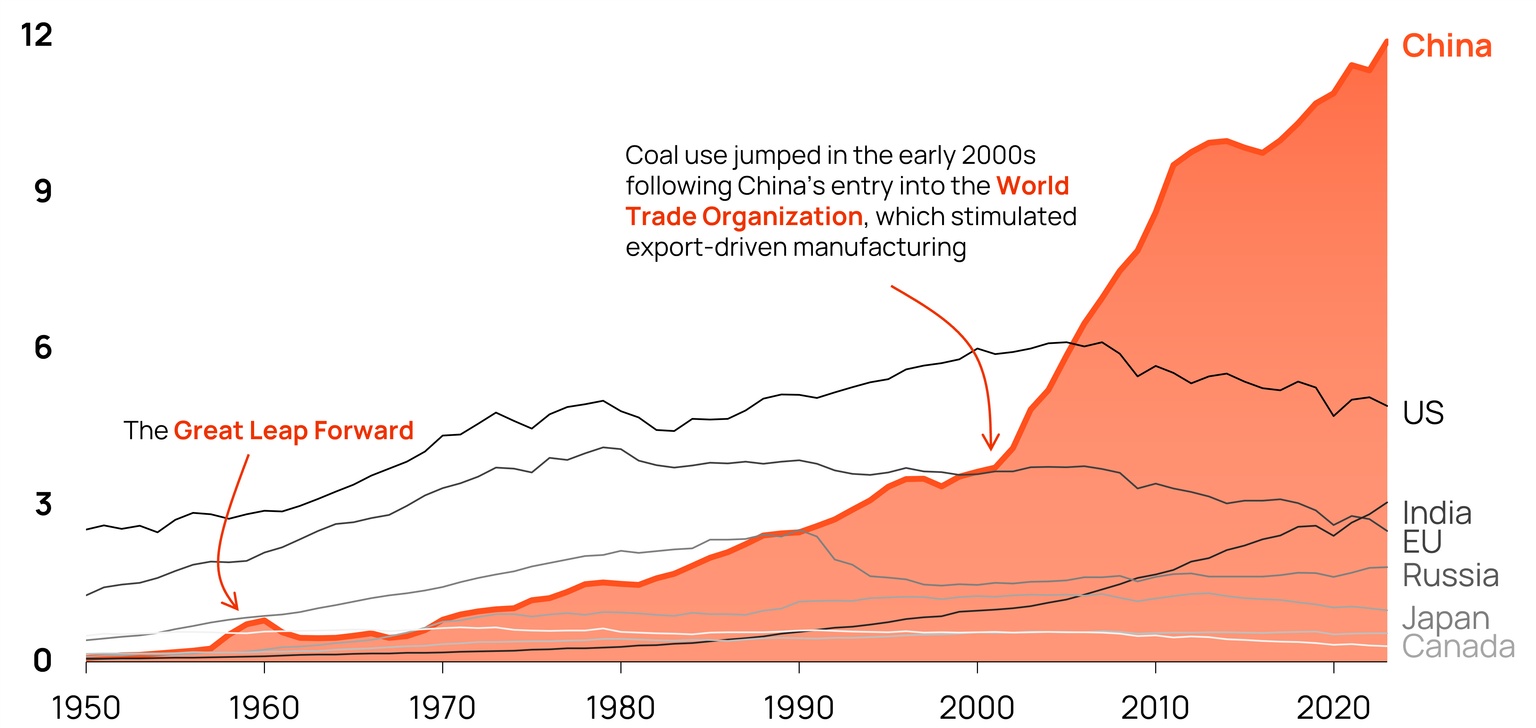

Let’s go back to the Great Leap Forward. At the time, China’s population was around 650 million, yet generated levels of carbon dioxide similar to Canada, population 18 million.

Following Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping took over as leader and reformed the economy. He installed the system more or less in place today, which looks a lot like capitalism in practice with key market mechanisms but is known as “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” the equivalent of referring to a steak as mashed potatoes with Texan characteristics. The industrialization that the market mechanism fostered led to growth in emissions.

WTO: Country emissions took off following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, when it was granted developing nation status — a status it still holds today — giving the country benefits in both trade and treatment. This gave export-driven manufacturing in the country a shot of ginseng and helped “Made in China” labels come into their own.

Chinese heavy industry got a boost from the 2008 financial crisis when authorities injected nearly $1 trillion in today’s dollars into the economy, mostly in the form of large infrastructure projects. That meant more steel, more cement, more power and, of course, more emissions.

It’s at this point that China overtook the US to take the title of world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and has since casually doubled its annual emissions rate. The export giant now accounts for a third of global human-related carbon dioxide releases.

The industrial firestarter: At the heart of growth for both Chinese industry and emissions is coal. Between 2000 and 2018, coal accounted for 75% of the country’s emissions, and there are currently 1.2 terawatts of operating coal-fired power plants in China, more than the rest of the world combined.

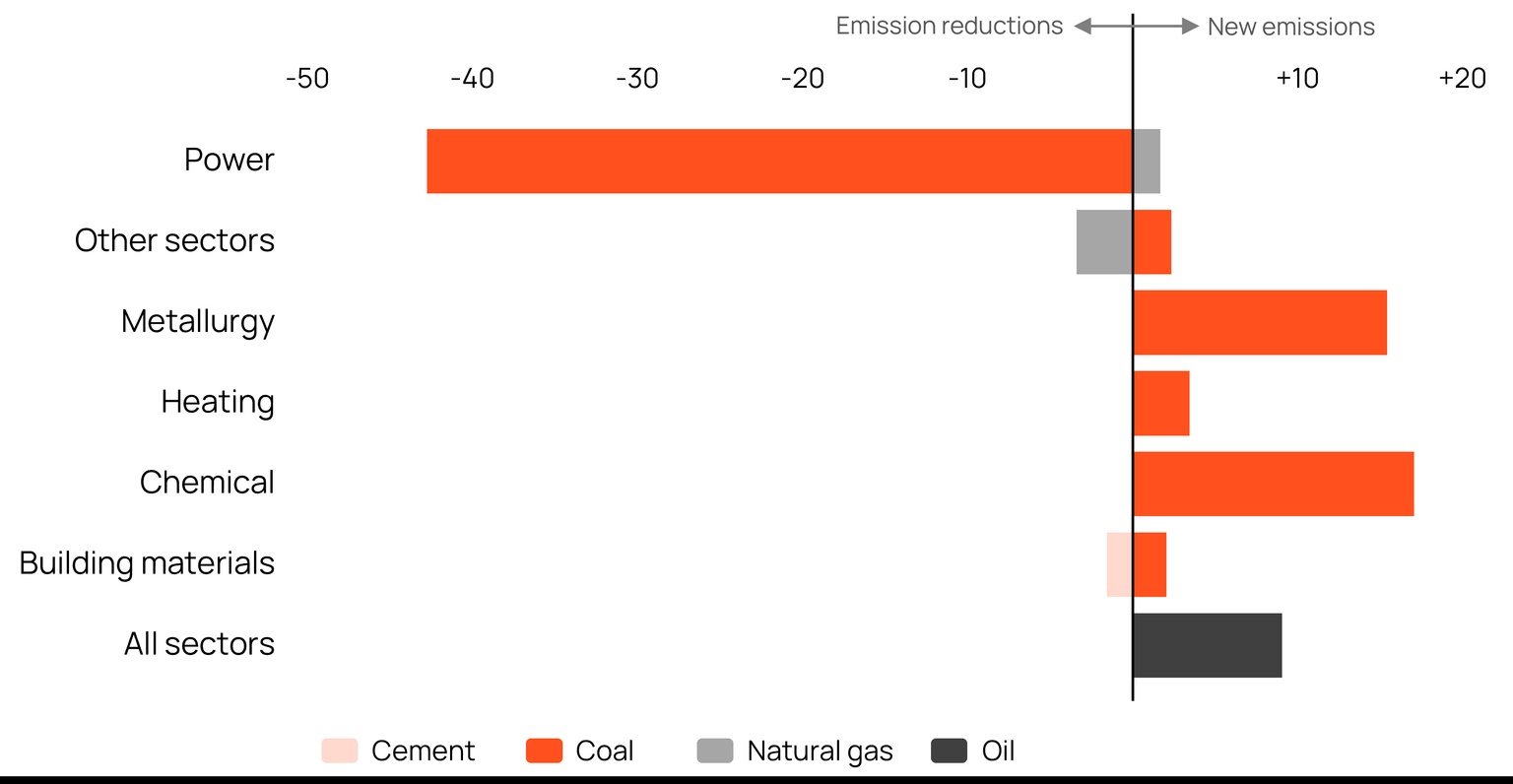

Source: Global Carbon Budget (2024)

But analysis from Lauri Myllyvirta at CRECA shows China may have finally peaked in March of last year.

It’s hard to deny the government’s role in curbing Chinese emissions. In 2014, then Prime Minister Li Keqiang spoke decisively on the country’s ambitions to improve the environment. “We will declare war against pollution and fight it with the same determination we battled poverty,” he said.

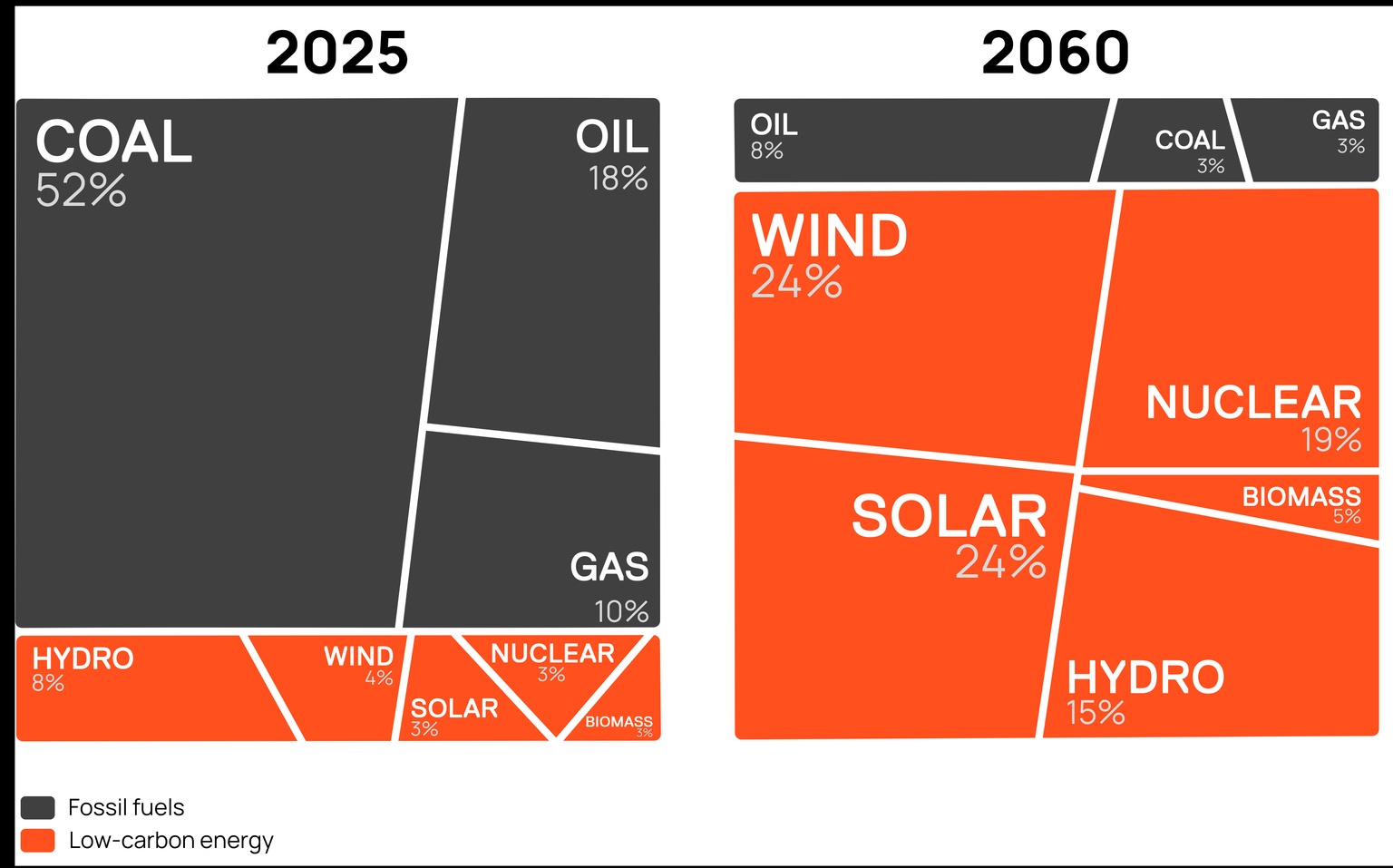

More formally, President Xi Jinping told the UN general assembly several years later that China would update its Paris Agreement pledge to reach carbon neutrality before 2060 and peak emissions by the end of this decade. These are the country’s “dual-carbon goals.”

Backing the pledge: Chinese policies are often clever wordplay. The country’s dual-carbon goals were also backed by dual-carbon controls, laid out in its 13th Five-Year Plan, calling for “implementing a system that focuses on carbon intensity control and is supplemented by total carbon emission control.” In the subsequent 14th Five-Year Plan, Beijing decreed that the country’s consumption of non-fossil power generation was to reach 39% by 2025.

Source: Tsinghua University’s Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development

In practice, this meant implementing a carbon market covering China’s coal-fired power plants. This created the world’s largest carbon market overnight, covering more than 40% of China’s carbon emissions and equivalent to 5.1 billion tonnes of emissions annually. Officials in Beijing have since approved a plan to incorporate cement, steel and aluminum into the national emissions trading system (ETS) starting this year. This will bring another three gigatonnes of Chinese emissions under the ETS, covering a scale of greenhouse gases larger than the entire American economy.

Big success: The results from Beijing’s policies have been nothing short of astounding.

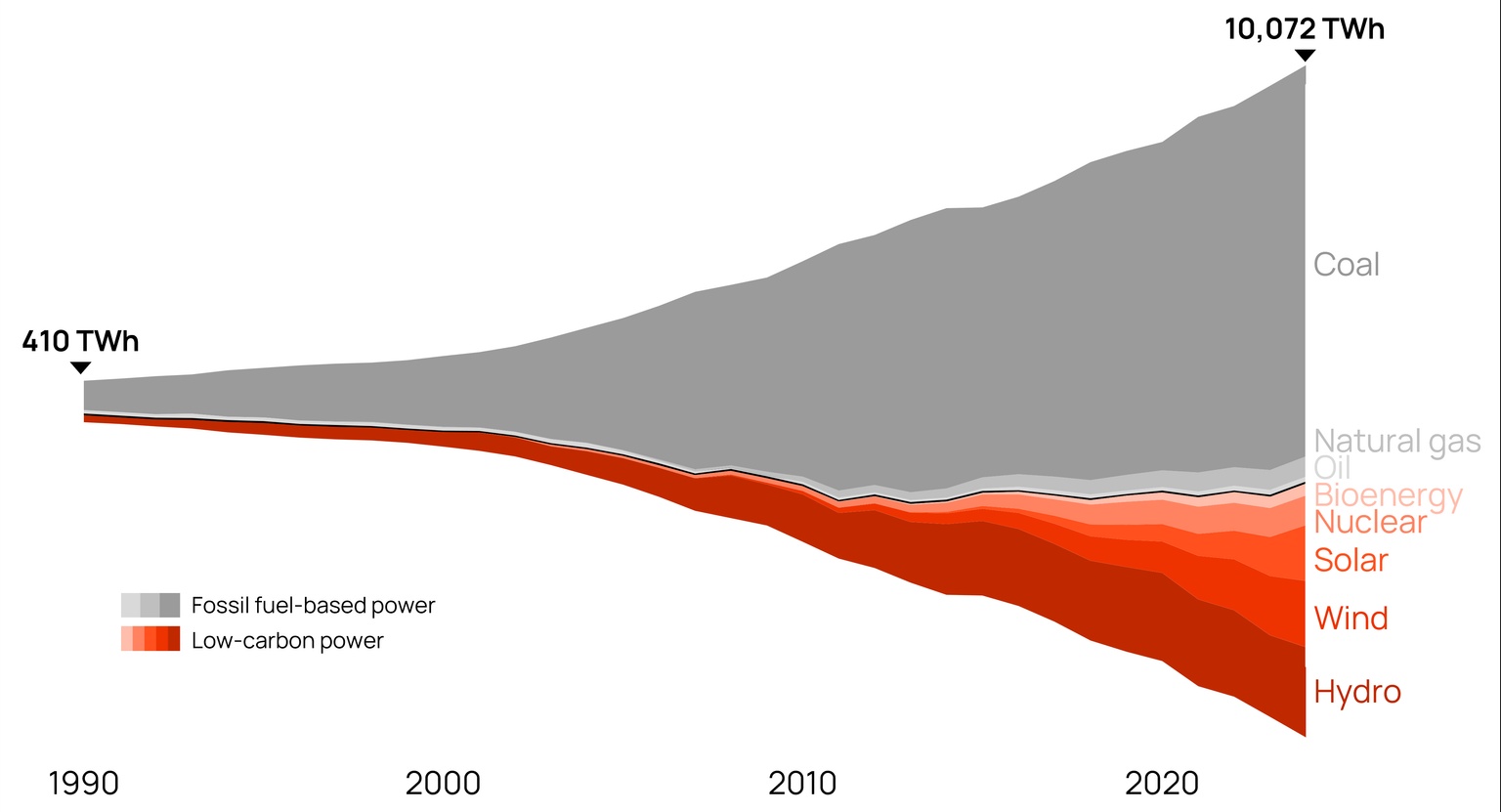

The Asian superpower added 356 gigawatts of wind and solar capacity last year. For context, that’s more than the US and Canada have added all-time. And in the first quarter of this year, there was more solar power installed on Chinese rooftops than utility-scale solar projects built across the US all last year — solar was the single largest source of new power in America in 2024.

Numbers involving China always look like someone did the math wrong.

Base power: It’s the remarkable growth of clean power, including hydro and nuclear, that has helped China peak its emissions. The supply of low-carbon electricity grew faster than the country’s load growth last year, dropping overall coal use and serving as the ultimate cause of the emissions decline.

Source: CarbonBrief

It would be unfair to give all credit to the power sector.

Shifting economies: Emerging economies often follow a cycle. Starting first as an agrarian society then followed by early industrialization, the broad population works as laborers to make ends meet. Not much left at the end of the day for a Nintendo Switch 2. But as industries and wages take off, laborers become consumers and industrial economies become service economies.

China’s economy is in the process of transforming into a service economy, which naturally emits less per unit of economic output. Punching in Excel formulas is less carbon intensive than operating an aluminum smelter.

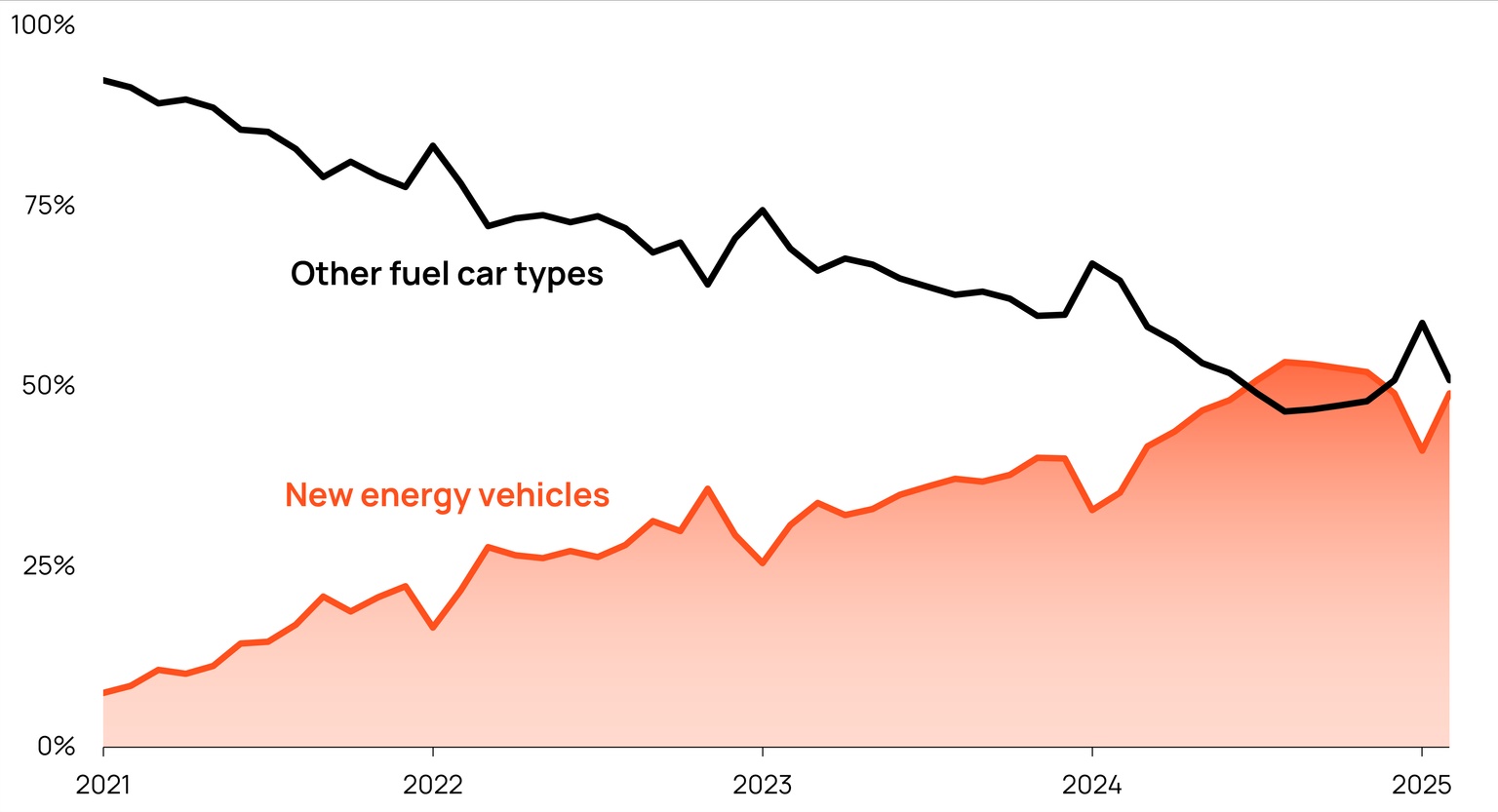

New energy vehicles: Whether you believe Beijing pushed for electric vehicles to avoid oil dependency on the Persian Gulf, to leapfrog western automaker dominance or just to avoid smog, China is now the single largest market in the world for electric vehicles.

With a careful balance of carrot and stick policies, Chinese authorities have orchestrated a change in consumer behavior that is almost without precedent. Half of all new cars sold in China today are electric or low emission, dubbed new energy vehicles. That share was hovering around 5% just a few years ago.

Source: China Passenger Car Association (CPCA)

Since Deng Xiaoping opened up China’s economy to market mechanisms, the country has lifted more than 800 million people out of extreme poverty. The rise of China has been, by far, the most important geopolitical event of the 21st century to date. Decarbonizing the state would be the most important environmental event, but don’t pop the Champagne just yet.

Similar claims have been made before, including back in 2016 by The New York Times. And China has stepped up its approvals of new coal plants after a quieter year last year.

Nonetheless, the country’s actions towards emission reduction have been impressive.

Bottom line: For those of us who’ve been around long enough to remember when China was the climate boogeyman, whose inaction justified our own inaction, that is no longer the case.

Far from being the country of peasants decimating forests to fuel backyard furnaces, China has become the industrial powerhouse it once sought to be, and now it has set its implacable gaze on decarbonization.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.