Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

It has to get worse before it gets better

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Since their inception at Expo 1851 London, world fairs have served to put the host nation’s achievements on display. An opportunity on the global stage for a country to show off its technologies and standing.

Chicago played host to the event in the late 19th century, holding the 1893 World’s Fair. On display were, what must have been, a dazzling array of electronic devices, including primitive fax machines, new telephones, an electric railway, neon lights and even Nikola Tesla’s Egg of Columbus.

AC/DC: It was here at the 1893 Chicago World Fair where the famous Current Wars between Tesla and Thomas Edison were ultimately settled. At the time, Edison and General Electric were pushing for direct currents (DC) to be used for the American electric grid. But it was Tesla, Westinghouse and the alternating current (AC) who came in with the lowest bid and ultimately illuminated the World Fair. The star attraction of the whole event was the brilliantly electrified Grand Basin floating pool, a display with over 100,000 lights.

Grand Basin lit with electricity from Nikola Tesla’s alternating current // Wikimedia Commons

Following its spectacular display in Chicago and due to its flexibility and reactiveness compared to direct currents, AC was ultimately adopted for the American transmission network. One of the key benefits of alternating currents is they help alleviate transmission congestion. This systemic issue, which drives up costs for consumers and can cause grid reliability issues, is once again creeping into the US grid. Estimated to have cost consumers $21 billion in 2022 alone, grid congestion is a growing problem with a need for solutions.

Transmission congestion is a symptom of a grid working beyond its design.

In a sense, it’s very similar to street traffic, with vehicles being the electrons and roads being the transmission lines. If designed poorly for volumes travelling at specific times, traffic jams form and limit movement. These electron traffic jams are grid congestion.

In flux: Like the growth of cities and changing driver behavior, the electric grid is also always being improved as new sources of both supply and demand are added, altering the flow of electrons. This is especially true today.

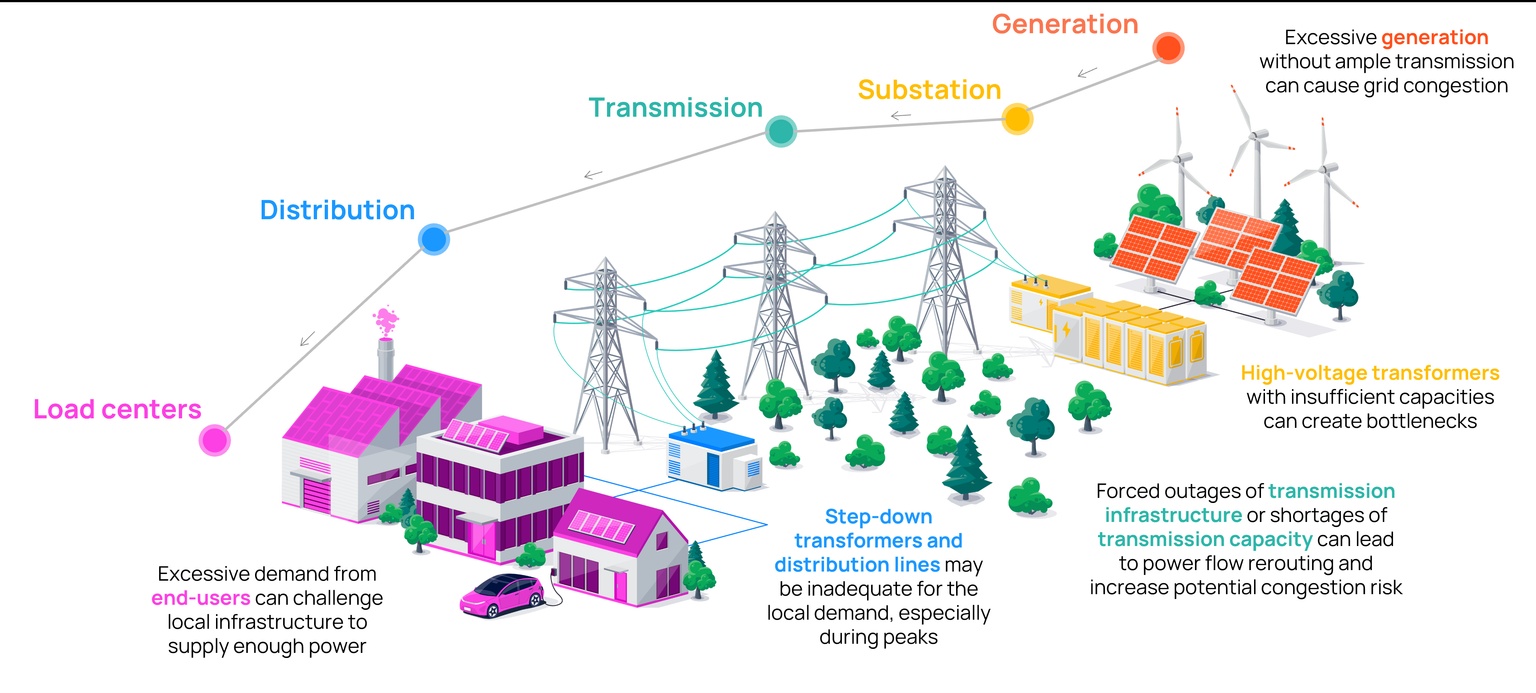

Source: Orennia

On the supply side, the rapid build-out of wind and solar is shifting where and when generation is taking place. While large traditional generators with predictable power flowed towards demand when needed, now there’s smaller variable generators all over the place. Thermal plants have also benefitted from ramping up and down to match anticipated demand. By contrast, new renewables generate sporadically, leading to periods of both over and under generation. In keeping with our traffic metaphor, it’s as though an entire city went from a predictable 9-to-5 workday downtown to shift work concentrated in multiple hubs.

On the demand side, the move for electrification and the acceleration of new large loads like data centers have renewed American electricity demand growth. The grid is really built to manage the moments of highest total demand, also known as peak load. As peak loads increase, so does the capacity of the grid. If the local last mile infrastructure can’t deliver enough power, it can put a ceiling on a region’s development and even limit electrification, like the number of homes in a community that can charge an electric vehicle.

Transmission lines are designed to handle a limited electrical current, known as the transmission line rating. If left unchecked, a transmission line will start to physically sag if it conducts more than its line rating. This is not the result of heavy electrons needing to jump on Atkins, but the metal wiring physically heating up and undergoing thermal expansion, which also slows the conduction of electricity.

In case of issue: To prevent overloading transmission lines, grid operators will curtail projects upstream of congestion from delivering power. This is usually done through economic curtailment, where the system operator reduces the supply from generators (often renewables) based on their economics bids to avoid congestion.

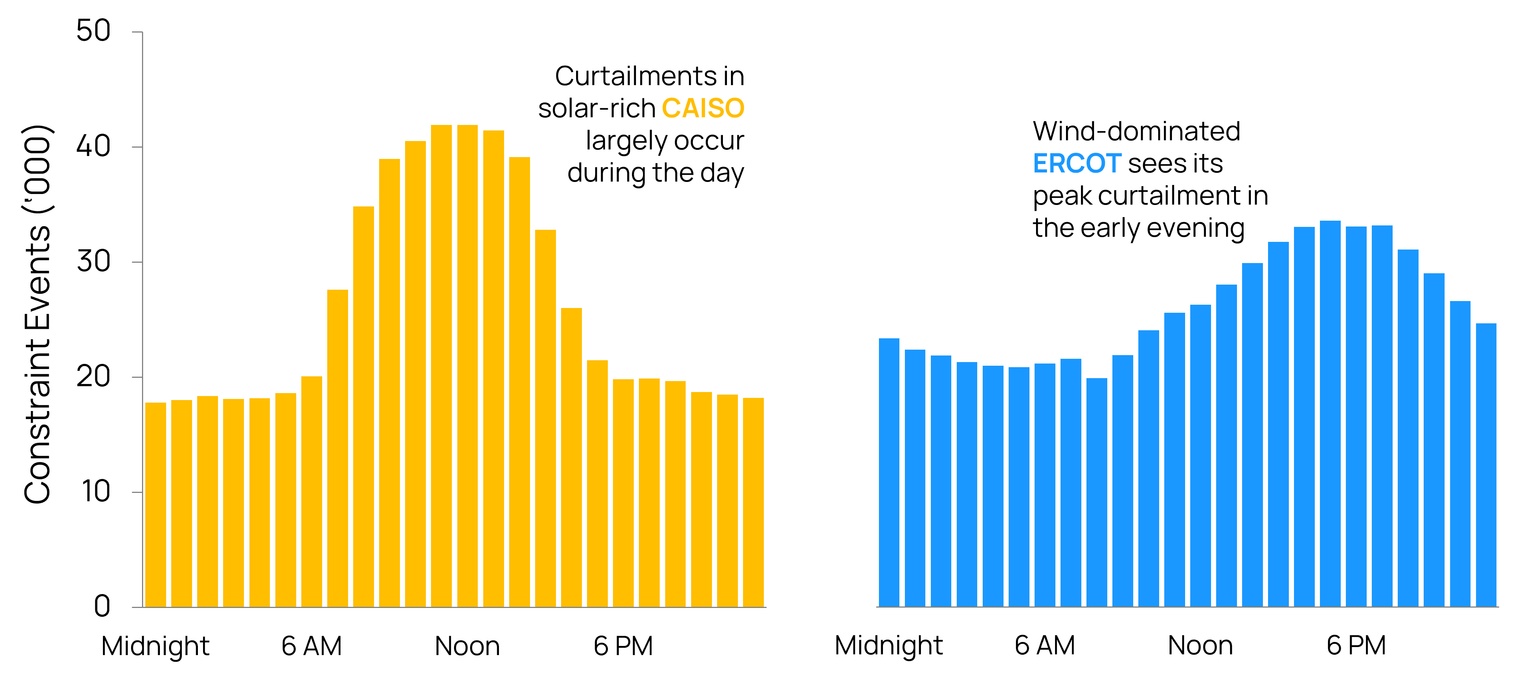

Source: Orennia

The time of day when projects are likely to be restricted depends a lot on where they’re located. In regions with an abundance of solar power, like California, curtailment mostly takes place during the day when solar production is at its highest. By contrast, in regions like the Texas Panhandle with plenty of installed wind capacity, the curtailments often happen in the evening when the winds often blow, but demand has wound down.

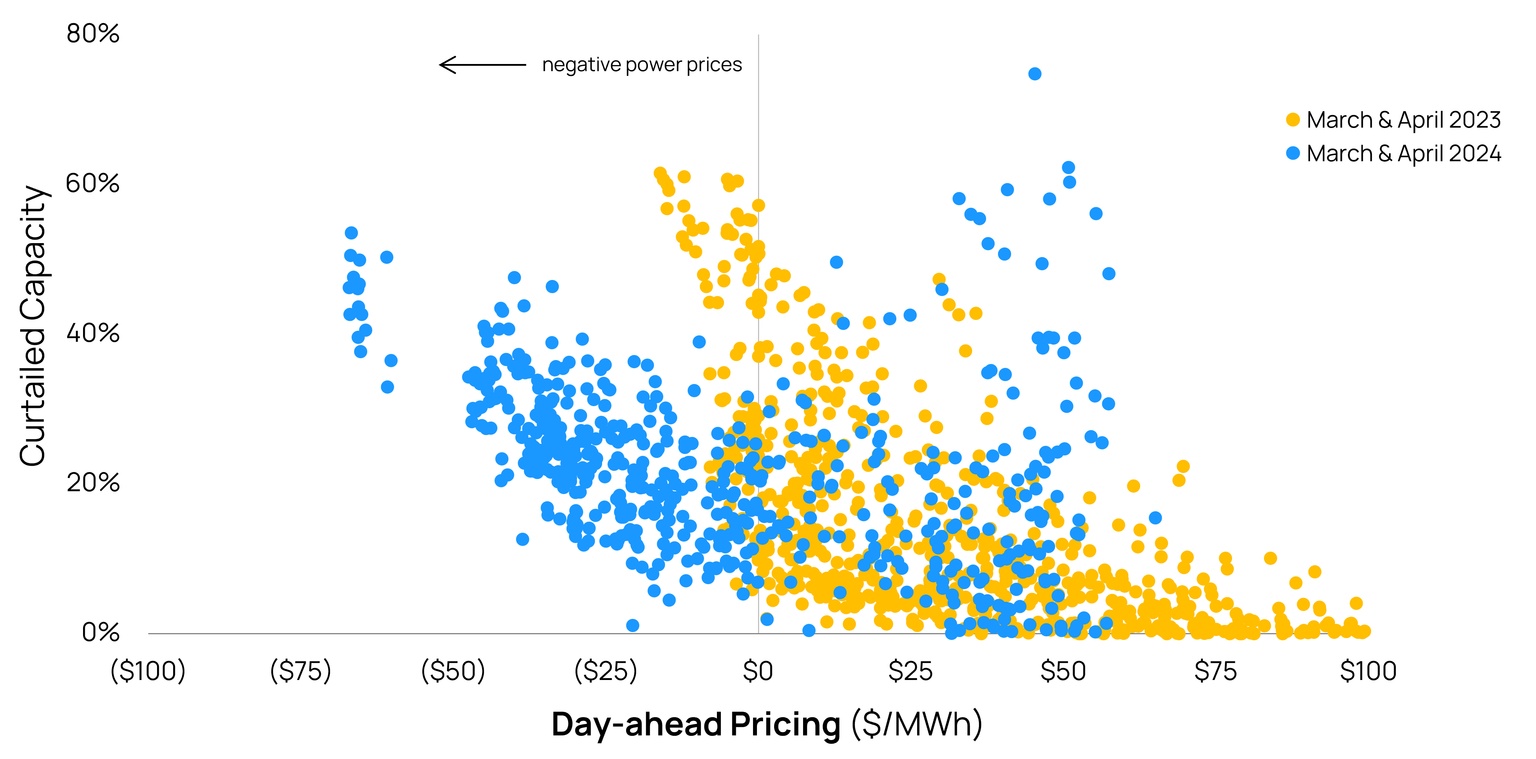

Congestion can also be seasonal. In the case of California, curtailment peaks in March and April when solar facilities are producing near summertime highs, but before the Malibu air conditioners have kicked into full gear.

As you might expect from the increased adoption of renewables, the amount of grid congestion events has been going up in recent years. Comparing the peak congestion months of March and April, the number of hours with solar curtailment in California Independent System Operator (CAISO) jumped from just 10% of hours in 2021 to nearly 20% this year.

Note: SP15 is the largest trading hub in CAISO; the high curtailment levels in 2024 when prices are positive reflect local congestion and are tied to nodal prices rather than hub prices

Source: Orennia, CAISO

Congestion is not great for consumers. As low-cost generation sources like wind and solar are intermittent and often further from demand centers, they often get curtailed leading to higher prices for buyers. According to consulting firm Grid Strategies, total transmission congestion costs were estimated to be $20.8 billion in 2022. This is a significant jump from 2016, when costs were just $6.5 billion.

The best way to reduce congestion is to increase transmission capacity – build more highways. This is no small feat.

The US power grid is considered to be the largest machine on earth and getting larger – roughly $75 billion was spent on transmission and distribution in the country in 2022. It’s made up of 7 million miles worth of transmission and distribution lines across the country, including 600,000 miles of transmission lines. Last year, the US consumed roughly 4,000 TWh worth of electricity. Therefore, every terawatt-hour of annual electricity demand uses ~125 miles of transmission lines and ~1,625 miles of distribution lines.

What’s needed: In order to meet the country’s growing clean electricity needs, the US Department of Energy (DOE) believes the country’s transmission system will need to expand high-voltage transmission capacity 60% by 2030 and tripling by 2050. A study by Deloitte estimates the cost to upgrade, harden, replace and build new transmission infrastructure in the US will total between $260 and $350 billion by 2030.

Source: Orennia

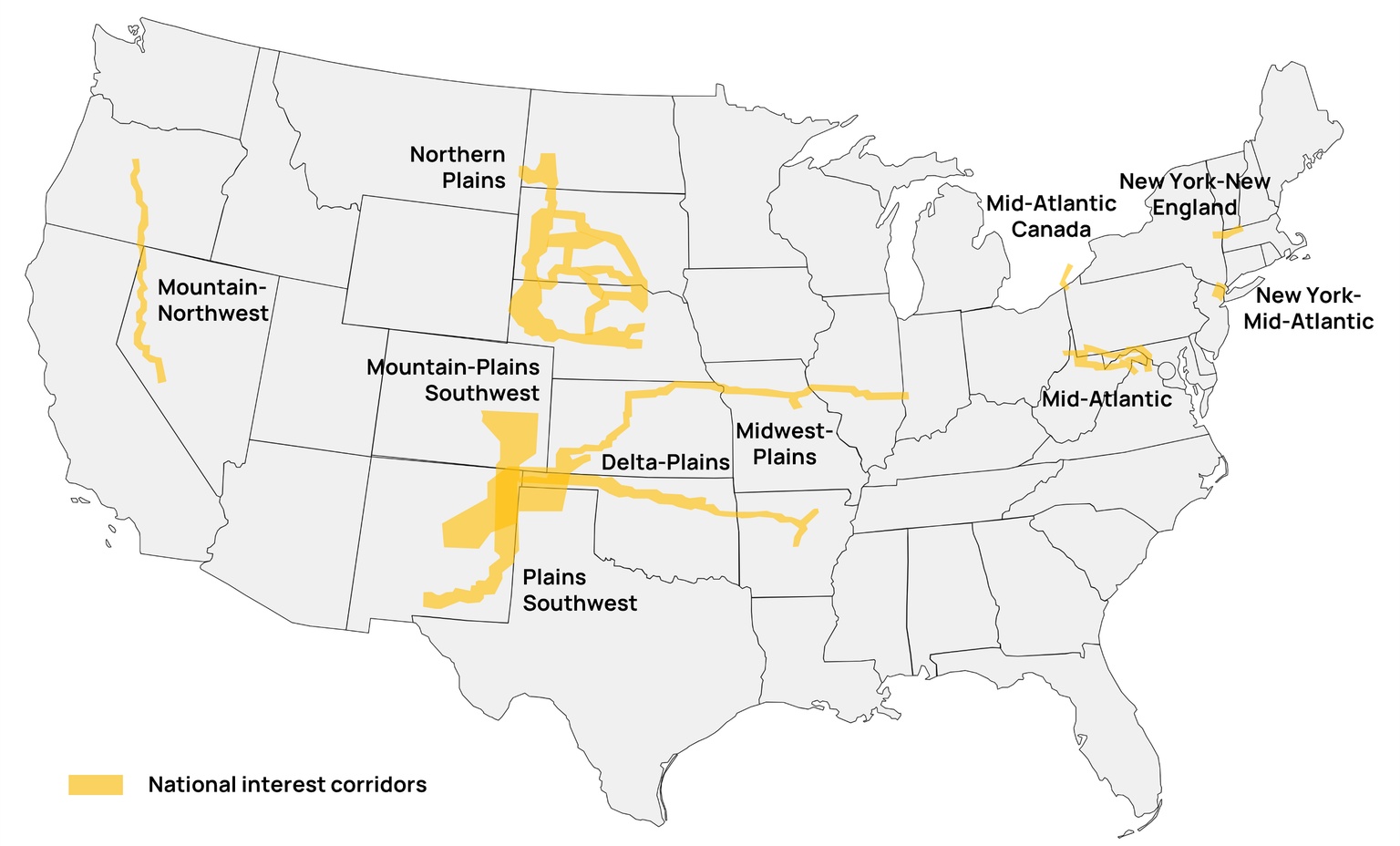

To speed up grid expansion, the DOE proposed ten corridors across the country. These “national interest electric transmission corridors” will extend more than 3,500 miles. Developing the corridors will allow companies to qualify for federal funding and allow for expediated development.

There are also other solutions beyond new transmission capacity that can make use out of existing infrastructure:

Getting more out of today’s grid is a clear win, but the transmission expansion is still needed, if even simply to transmit electricity from new generating regions. This may be another example where utilities and consumers are at odds. Grid enhancing technologies may be less expensive to deploy, which would be good for the consumer, but less lucrative for utilities.

Transmission and congestion are increasingly in focus for developers. Data centers are scouring the country looking for locations on the grid that can meet their power-hungry needs and provide reliable 24/7/365 electricity.

Understanding where congestion is happening today and how it’s changing can be the difference between a project going ahead and being cancelled.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.