Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Soil, but supercharged

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Despite what its lush forest canopies teeming with howler monkeys portray, the soils of the Amazon rainforest are remarkably infertile. Heavy Amazonian rains tend to wash away valuable nutrients, leaving behind an iron- and aluminum-rich acidic topsoil with characteristic reddish coloring.

To help make the Amazon more habitable, the Indigenous Amazonians created a soil better suited for human agriculture. Black and exceptionally fertile, “terra preta” is a dark soil with high levels of phosphorus, calcium, potassium and nitrogen—ideal for happy plants. It’s also self-sustaining and regenerative, something even modern western farming techniques struggle to replicate. Some of the thousand-year-old terra preta soils remain fertile today.

The secret: It remains an unsolved mystery whether the soil was created by design or serendipitously, but the presence of a charcoal-like substance, shards of pottery and animal bones clearly point to human involvement. Charcoal is the key.

When organic material undergoes a full burn with fire, it turns to ash, a powdery material that can easily wash away. But if the process happens without oxygen, what’s left afterwards is a stable, carbon-rich material that can be locked into the soil for centuries.

A farmer holding terra preta (left) and typical Amazonian soil (right) // Wikipedia Commons

Fast forward two and a half millennia and being able to store carbon is now big business. Scientists and engineers are actively trying to find scalable ways to capture atmospheric carbon and store it. At the same time, many of the emerging clean technologies rely heavily on selling credits at a time of heightened policy uncertainty.

Can this special type of charcoal made from an ancient farming technique known as biochar be the future of climate technology in these uncertain times?

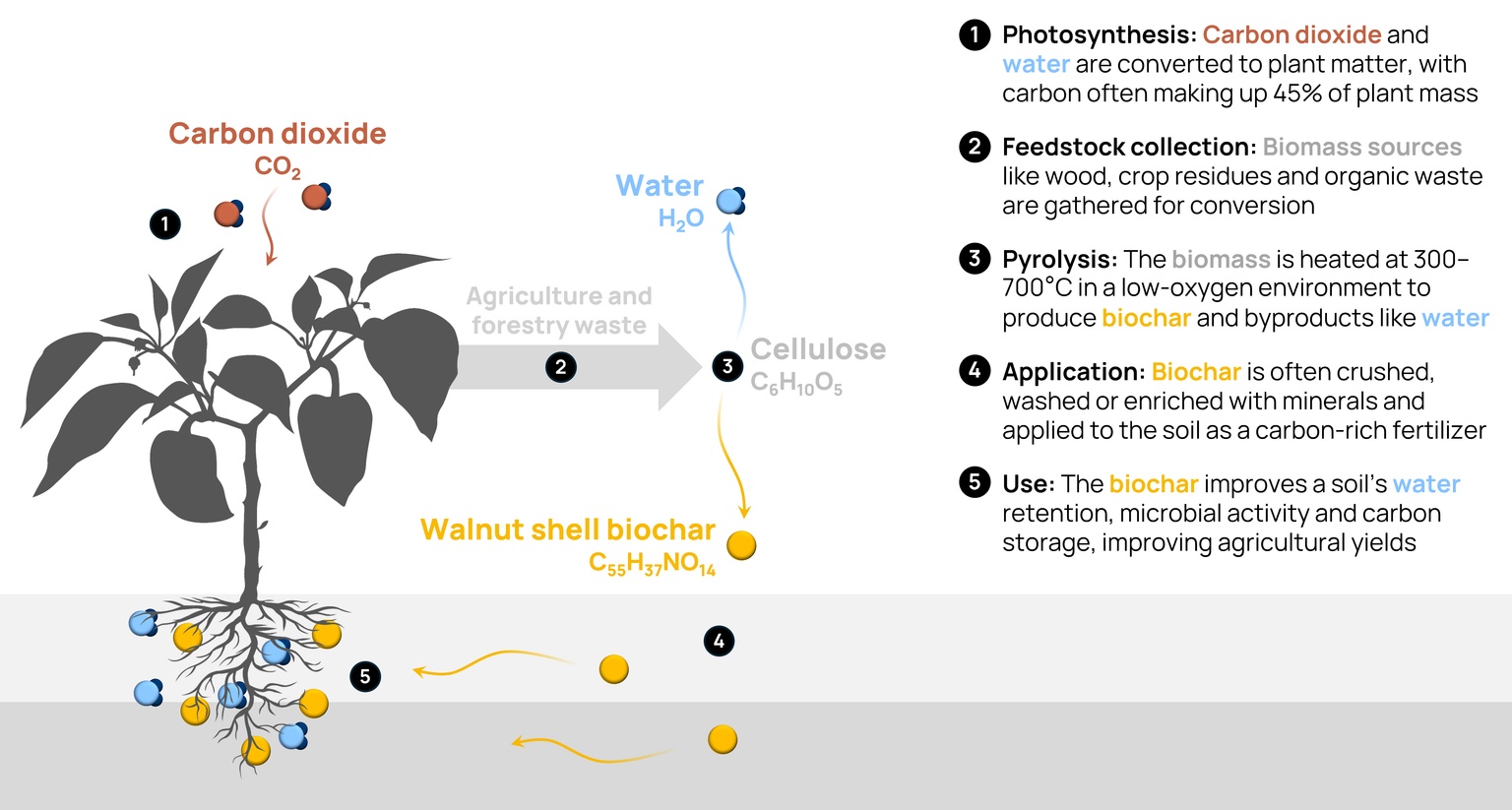

You can think of biochar as the concatenation of biomass and charcoal, “bio” and “char,” though it is not identical to charcoal. Both biochar and charcoal are made by cooking organic content in a low-oxygen environment, a process known as pyrolysis. The lack of oxygen prevents full combustion and avoids the release of carbon dioxide.

Charcoal vs. biochar: If pyrolysis happens at lower temperatures — 300 to 700 degrees Celsius — the material retains more of its original oxygen and hydrogen. What’s left is a stable and porous structure that, when put into the soil, can hold onto water and nutrients like they’re at the starting line of a marathon. This is the biochar created by the Amazonians for terra preta.

By contrast, if pyrolysis temperatures are raised to the 700-to-1,100-degree range, what’s left is mostly carbon and known as charcoal — great for a broil, not for the soil.

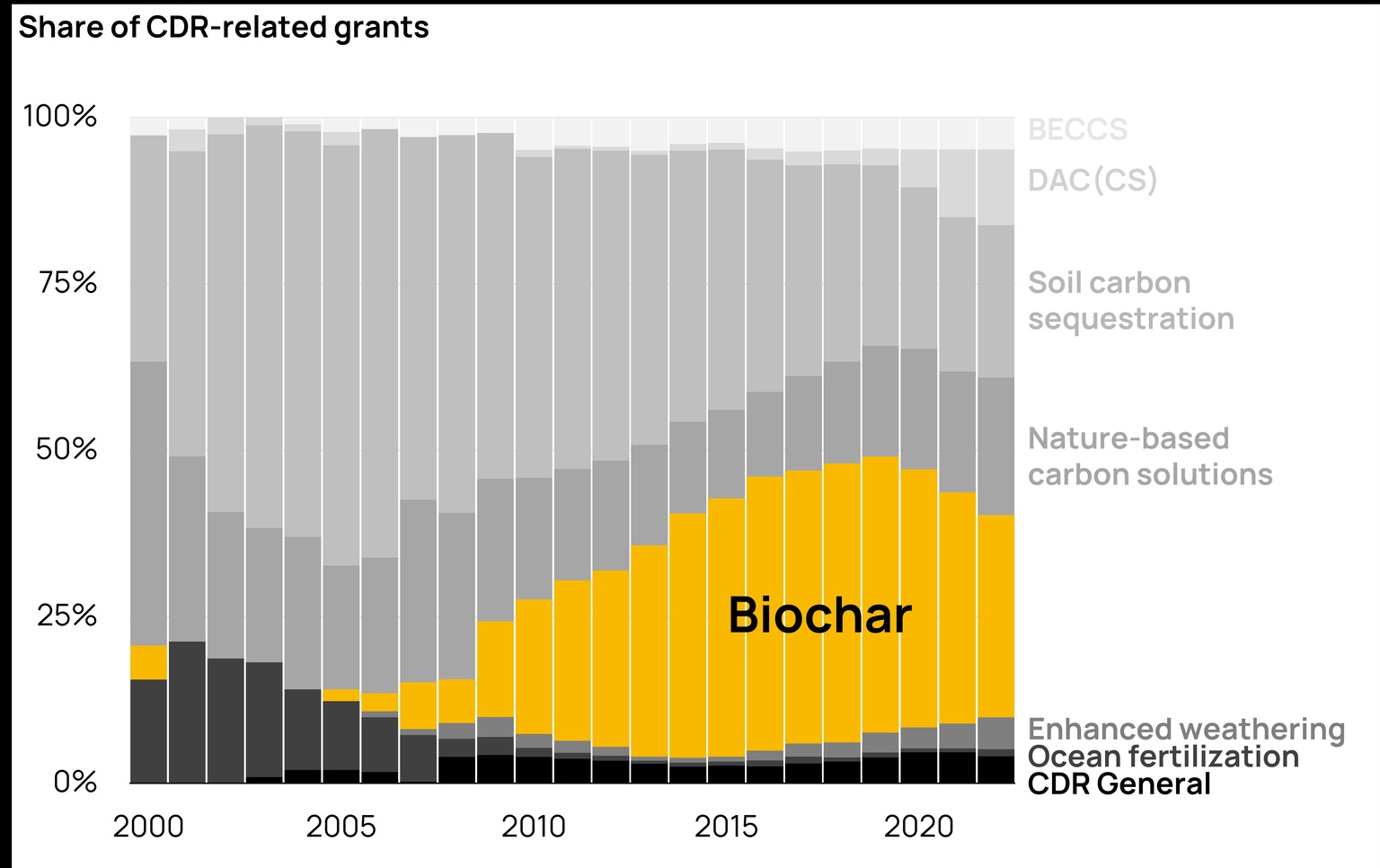

Through its unique ability to both store carbon and foster plant growth, biochar has unexpectedly emerged as one of the top solutions to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In last year’s State of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) report published by the University of Oxford, biochar was noted as being the most-used technology globally apart from planting or replanting trees to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, far ahead of more headline-grabbing technologies like direct air capture.

But why?

The key is breaking the carbon cycle. By taking something carbon-based that would have otherwise been burned or eaten and turning it into a stable product, carbon is taken from the atmosphere and put in the ground. Direct air capture but with walnut trees.

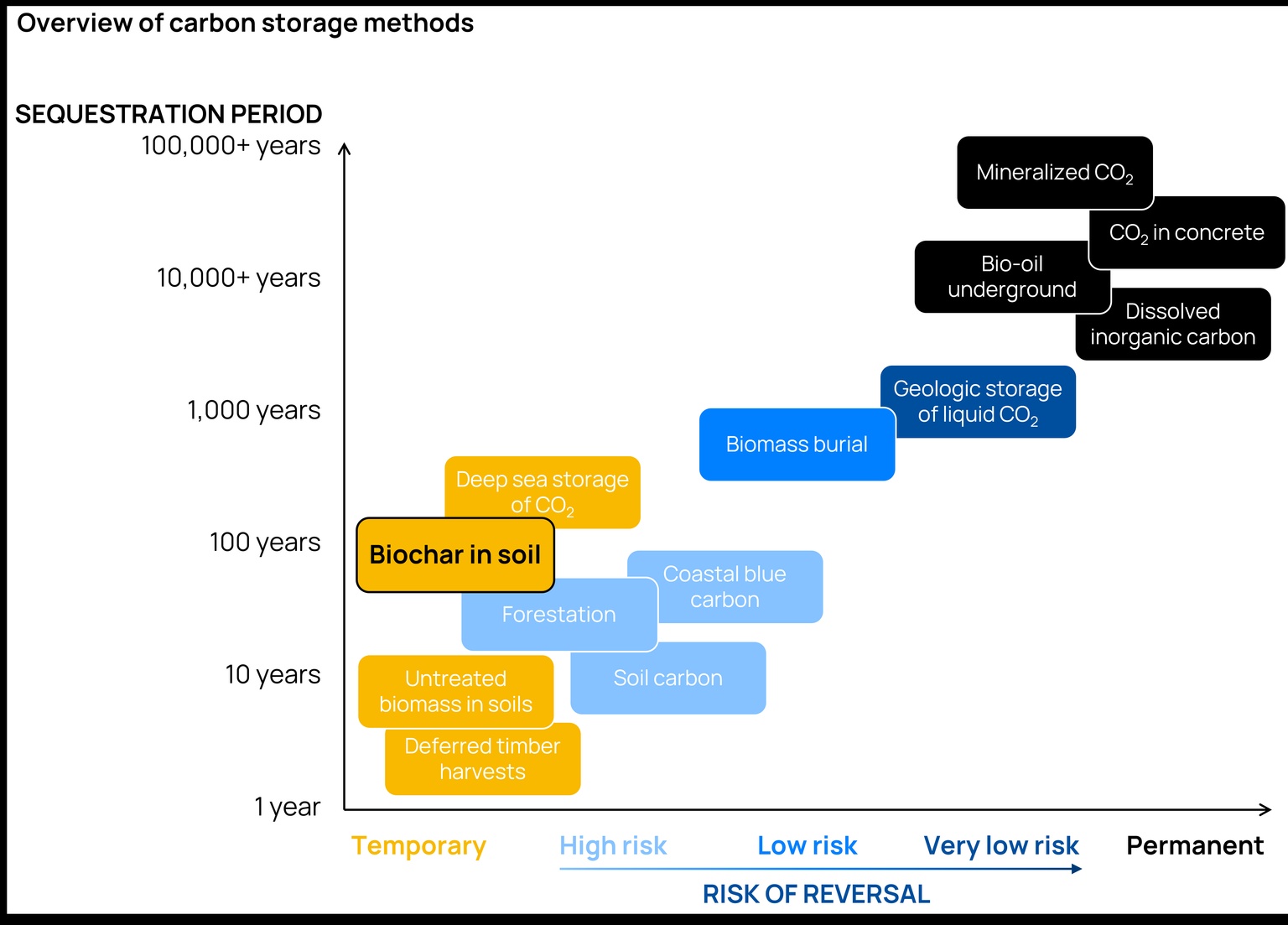

Locked away for centuries: Because of its chemical stability, putting biochar in the ground leaves it there for a while. Researchers at Ohio State University published a meta-study on how long biochar can stay in the soil and confirmed it can sequester carbon for hundreds to thousands of years.

Chart modified from Robert Höglund / Marginal Carbon

Biochar’s carbon will eventually make its way back into the carbon cycle, making it a temporary solution. But even sequestering carbon for several hundreds of years allows time for other carbon emission reductions to take place.

Soil, but supercharged: A key benefit of biochar is not just that it stores carbon underground but that it helps plants grow.

Underground, water acts as UberEats — delivering key nutrients to the roots. Without water, plants can’t get sufficient building blocks needed for their growth so being able to retain more water is a big help. A study by the University of California found that even just a 5% application of biochar increased the water retention of soil by 20% to 25%, especially beneficial to regions already prone to drought.

Biochar also helps with the microbial activity of soil. If water is the UberEats delivery service, it’s microbes that do the eating — breaking down organic matter into minerals like phosphorus, potassium and sulfur for root absorption. The porous structure of the biochar acts as a hotel for microorganisms, providing shelter and a home for nutrients that lead to better overall soil health and plant growth.

Putting the two together, biochar helps to grow vegetation across a wide range of conditions. Chinese researchers found crops were on average 13% more productive by applying biochar, reaching up to 20% depending on the crop. To put that in perspective, fertilizers boost crop yields by 40% to 60%.

It’s the fertilizer angle that makes biochar particularly interesting.

Most carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies earn revenues solely through selling credits to willing buyers, most of which are large companies with their own climate targets. As carbon dioxide is considered a waste product for most businesses, dealing with captured carbon is effectively a waste tax. This is true for geologic storage of carbon dioxide, mineralization and buried biomass.

Source: The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal, 2nd Edition, University of Oxford

Luckily for biochar, being able to better grow food is big business. In 2023, the leading American ag retailers generated $22 billion in revenue just from fertilizers alone.

The economics: To buy woody biochar at scale today costs roughly $350 per ton. In order to see better crop yields, it’s believed that farmers would need to add 10 tons of biochar per acre to their lands. Add another $10 per ton to apply it, and that’s $3,600 to add biochar to an acre of farmland.

To put that in context, the University of Kentucky publishes annual estimates on the economics of various crops across the Midwest. Your average acre of Kentucky corn farmland used $210 worth of fertilizers for a gross return of $305 last year. In other words, biochar currently costs about 12 years’ worth of corn margins or 15x what a typical farm will pay for fertilizer every year.

As biochar only needs to be applied once every 10 or more years for the benefits to crops, it’s not a perfect comparison. For a soil enhancement product, it’s more expensive than modern nitrogen fertilizers and yet provides less of a benefit by way of higher crop yields. It doesn’t exactly sell itself, so needs some support.

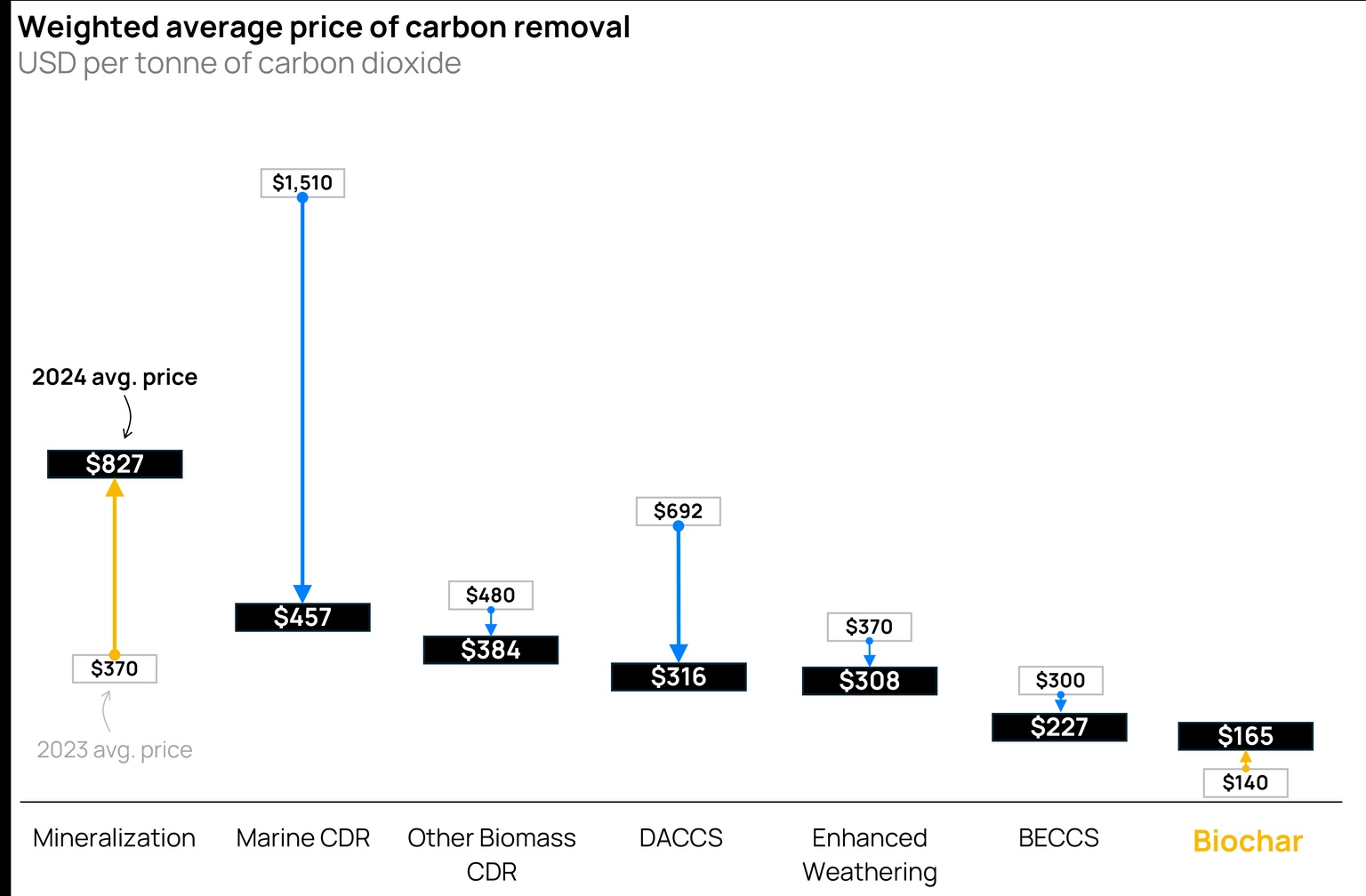

Credits: To bridge the difference, biochar can earn CDR credits for storing carbon underground that would have otherwise ended up in the atmosphere. And because it’s already a fairly inexpensive product to make and can earn additional revenues by selling as a soil enhancer to farmers, biochar CDR credits are the lowest cost among the emerging technologies.

Source: CDR.fyi’s 2024 Year in Review

As interest in biochar product grows, there is reason to think costs will continue to come down.

For one, studies have shown economies of scale likely play a big factor in production prices. A shift to large-scale pyrolysis facilities will reduce future biochar costs. And being able to secure cheap materials to convert into biochar can help, too — like using agricultural waste, similar to what’s been done with biofuels. Two projects in the US are incorporating biochar with forest management, using deadwood to make the carbon-based product, which also reduces wildfire risk.

The scale: While it’s still early in understanding biochar’s true potential, the scale of human impact is well studied. Research led by the University of British Columbia estimates that biochar made using residues from agriculture, livestock, forestry and wastewater treatment could remove 6% of all global greenhouse gas emissions across 155 countries. And its potential is going mainstream.

Late last year, Senken and Exomad Green signed a deal for 81,600 tonnes of biochar carbon removals, the equivalent of taking ~18,000 cars off the road for a year. And earlier this year, Google announced two 100,000 tonne deals buying credits, the largest-ever biochar-based carbon removal agreements.

There is a natural human tendency to view solutions of the future being tech-heavy, but what if they weren’t?

The Amazonian terra preta may have come about completely by accident, certainly with no understanding of biochar’s impact microbiology. Yet, it’s been a solution for soil issues that endured for hundreds of years. Of the CDR technologies that can realistically sequester carbon for hundreds of years, it’s one of the only ones that has alternative revenue streams beyond selling credits. And the whole process is like carbon jujitsu, turning agricultural and forestry waste into a carbon sequestration solution.

Bottom line: As nature enthusiast Sir David Attenborough once put it, “We need to work with nature, not against it.”

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.