Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

What is the impact of China's restrictions on access to critical minerals?

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

In the early days of the Cold War, there was an American-Soviet technology race between evade-and-escape capabilities in the air and detect-and-destroy capabilities on the ground. That came to a head in 1960 when an American U-2 spy plane running a reconnaissance mission over Russia was shot down by a Soviet surface-to-air missile.

Innovation: The CIA, at the time responsible for US surveillance aircraft, decided a new type of plane was needed to avoid a similar situation, so turned to Lockheed Martin. The Skunk Works team, led by famed aircraft designer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, came up with just the plane for the job: the famous SR-71 Blackbird, every 8-year-old’s favorite jet fighter and the most iconic plane of the Cold War.

Designed to travel at Mach 3.0, three times the speed of sound, the plane flew at a pace other planes could only achieve briefly using afterburners. It was so fast, the Blackbird didn’t need to worry about missiles, it could simply outrun them.

Source: The SR-71 Blackbird // GoodFon

For all its genius, the plane’s design came with two major challenges. The first was that the heat generated on the plane’s exterior from traveling at those speeds would warp aluminum, the traditional metal used for fighter jets. Titanium was therefore selected for the frame, which gave the Blackbird its iconic coloring and namesake. According to former Blackbird pilot Col. Rich Graham, “the airplane is 92% titanium inside and out.”

The use of titanium, though, led to the second problem: the US didn’t control the ore supplies needed to produce sufficient titanium for the program. It just so happened the country that dominated global titanium ore supplies was the USSR, the very nation the SR-71 was being developed to spy on. Quite the pickle.

Undeterred, the CIA began a clandestine program to buy titanium from the Soviets through a series of shell companies and intermediaries under the guise the metal was needed for pizza ovens.

Enough titanium was eventually secured to build more than thirty SR-71s, with material left over for a dozen or so other derivative planes. Maybe even a pizza oven or two.

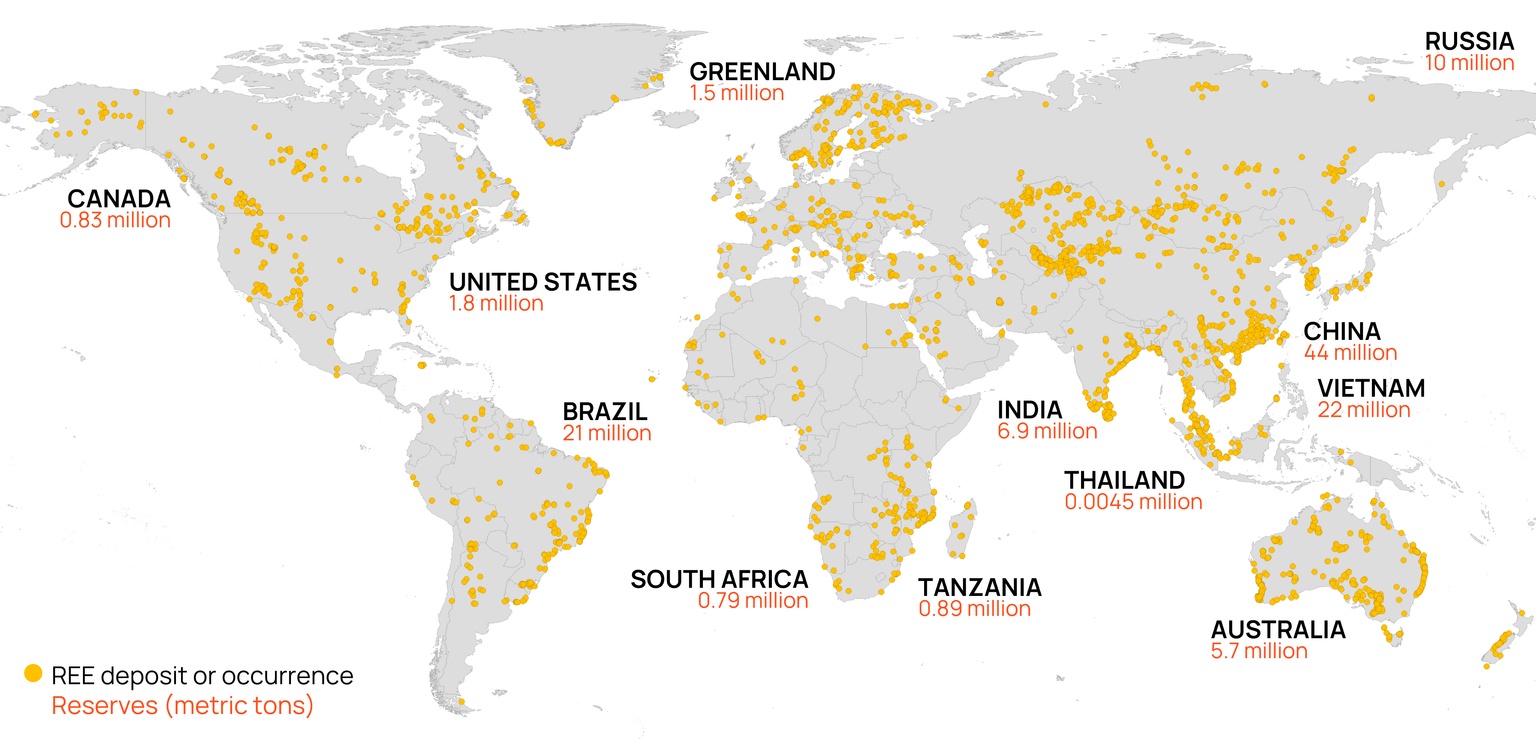

Modern mineral mess: Fast forward to today and the US once again finds itself in a critical mineral bind, this time with its contemporary geopolitical and technological rival China. Following the launch of the White House’s recent trade war, the governing Chinese Communist Party has moved to restrict access to other critical minerals: rare earth elements.

Rare earth elements are used in everything from consumer electronics and clean energy technologies to critical defense systems, yet China has near monopolistic control over the entire supply chain. The Asian superpower’s export controls could severely impact America’s ability to build a modern 21st century economy and keep pace with national defense.

So how big of an issue is China’s trade move and what can be done about it?

Let’s dig in.

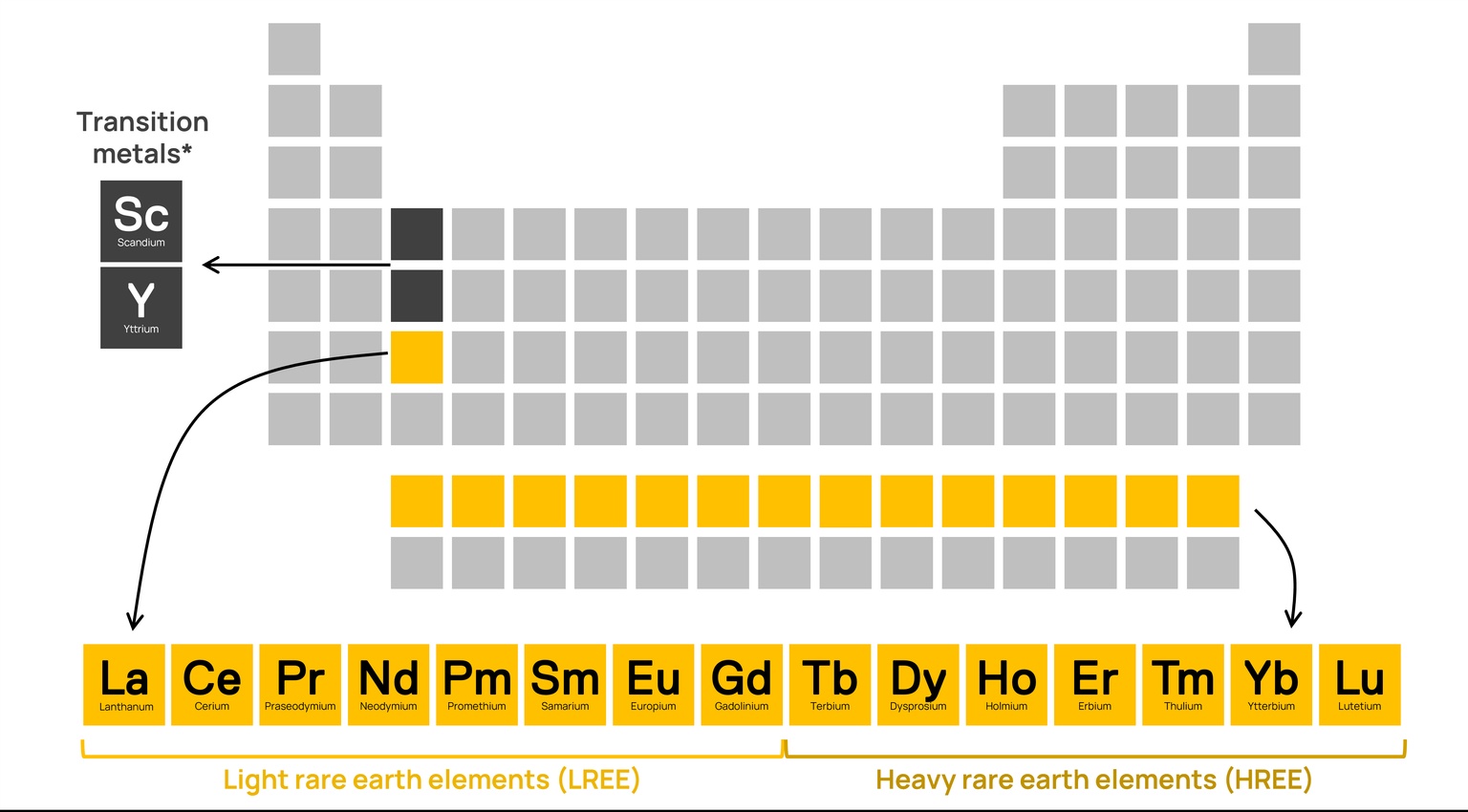

A good place to start is the periodic table: rare earth elements (REEs) cover 17 metallic elements, including the 15 lanthanides plus the transition metals yttrium and scandium, which share similar chemical properties and are found in similar ore bodies.

Rare earth elements are ironically not all that rare in the Earth’s crust: cerium is the 25th most abundant element on the planet. But like the frustratingly limited oat clusters in Honey Bunches of Oats breakfast cereal, meaningful concentrations of REEs in ore deposits are rare to find.

Even once ore is identified and mined, extracting the individual metals is no joke. For one, the fact REEs are usually all found together and have similar properties means separating them becomes a feat of modern metallurgy. And given that they’re often found alongside minerals like uranium and thorium, the waste is, at best, toxic, and, at worst, radioactive.

Let’s just say there’s a reason so much rare earth stuff happens in China.

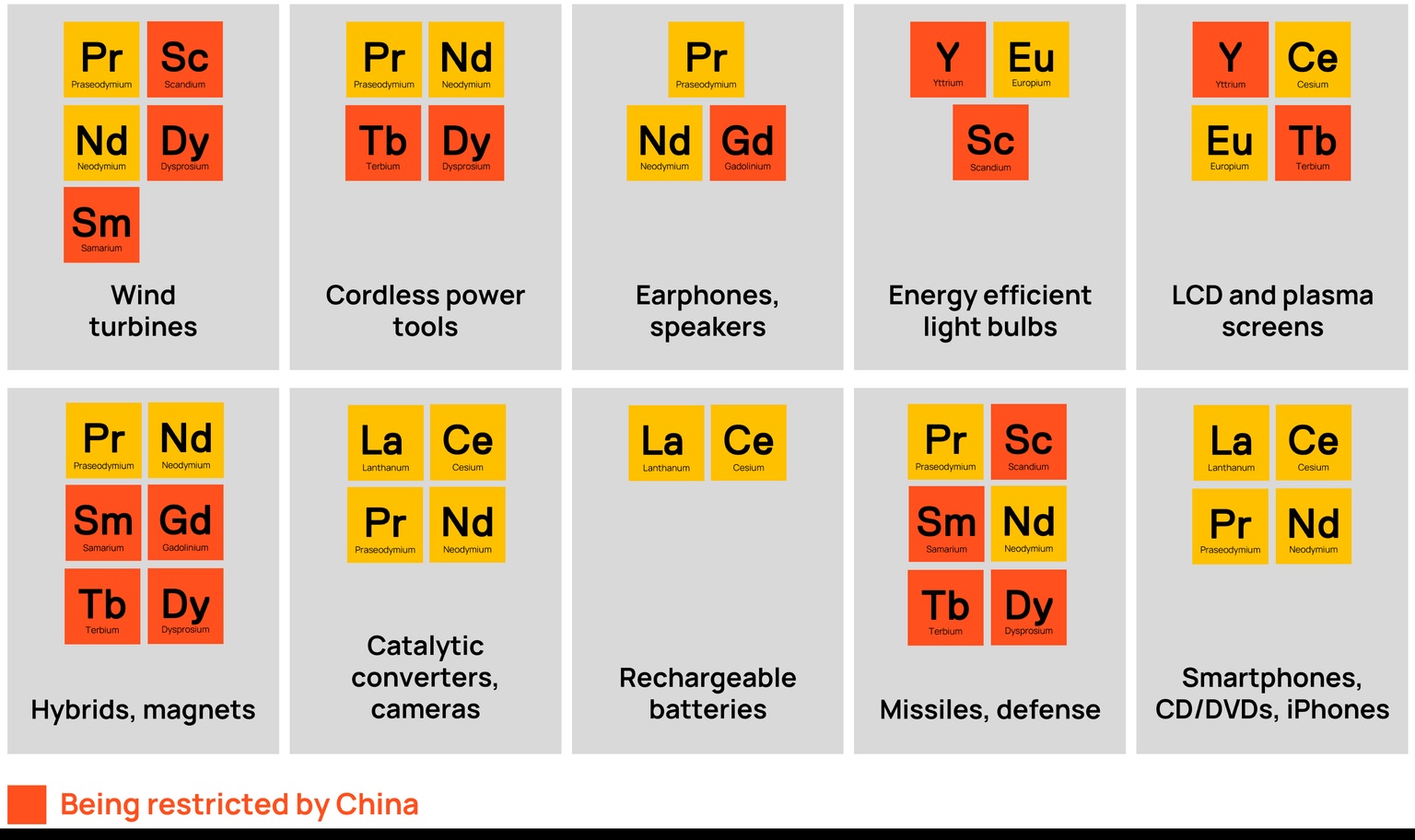

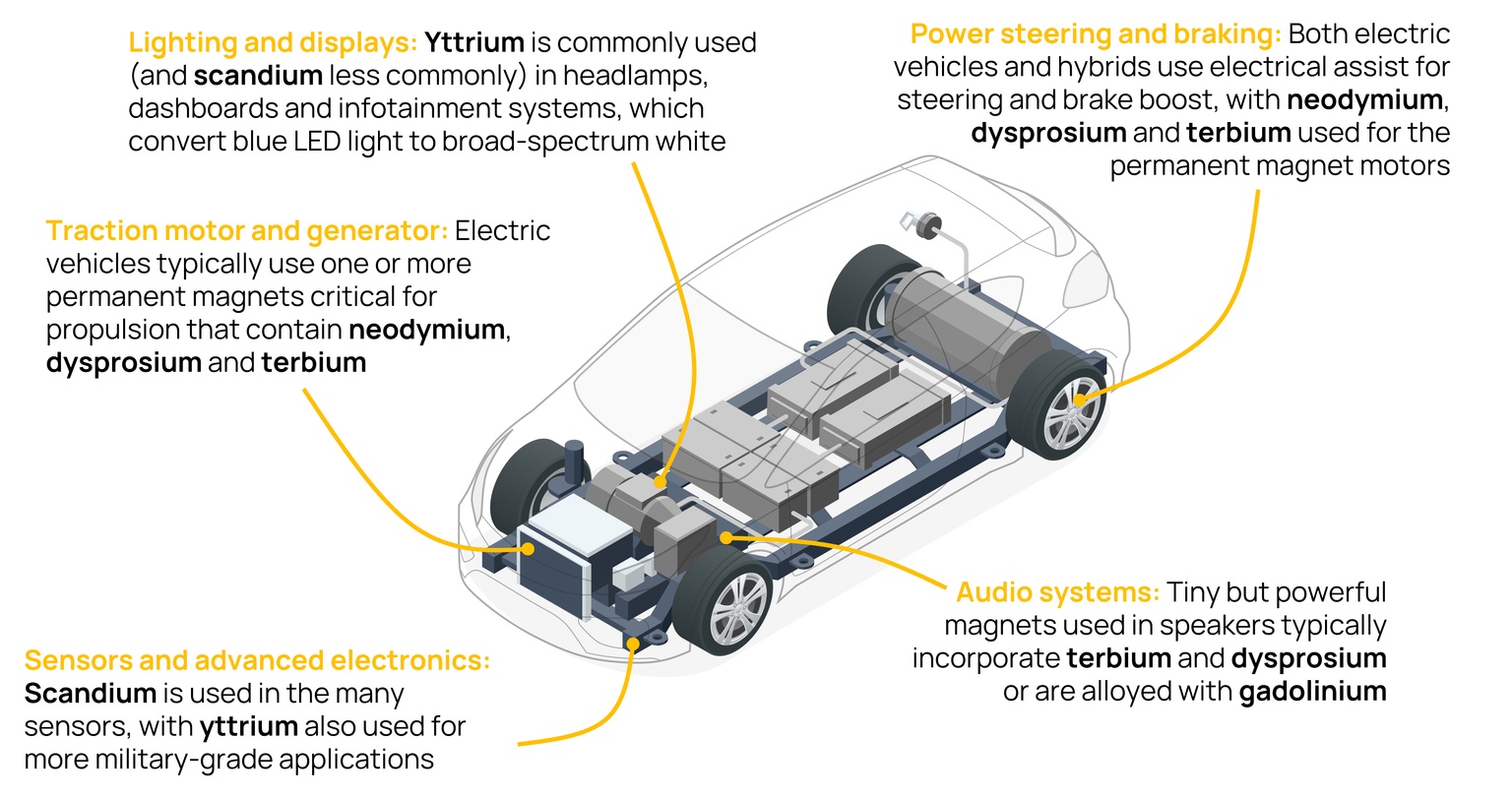

Their use: Because of their unique magnetic, luminescent and electrochemical traits, REEs are indispensable in a wide range of modern tech. Some of the metals, including neodymium and dysprosium, create the strongest known permanent magnets, essential for electric vehicle motors and missile guidance systems. Others, like scandium and yttrium, are highly heat resistant and thus vital for nuclear reactors and jet engines.

Source: Modified from Stratfor

Europium, yttrium and terbium are phosphors — which glow under UV light and can be used for high-definition displays and LED lights — while lanthanum and cerium are key for rechargeable batteries and hydrogen storage systems. Their uses are as numerous as their unpronounceable names.

Given both the criticality of REEs in so many technologies and general animosity toward monopolies, it was a true strategic blunder on the part of the West that one country was allowed to develop and own nearly the entire production network.

As far back as the 1970s, China recognized the strategic importance of REEs. As former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping put it four decades ago: “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.”

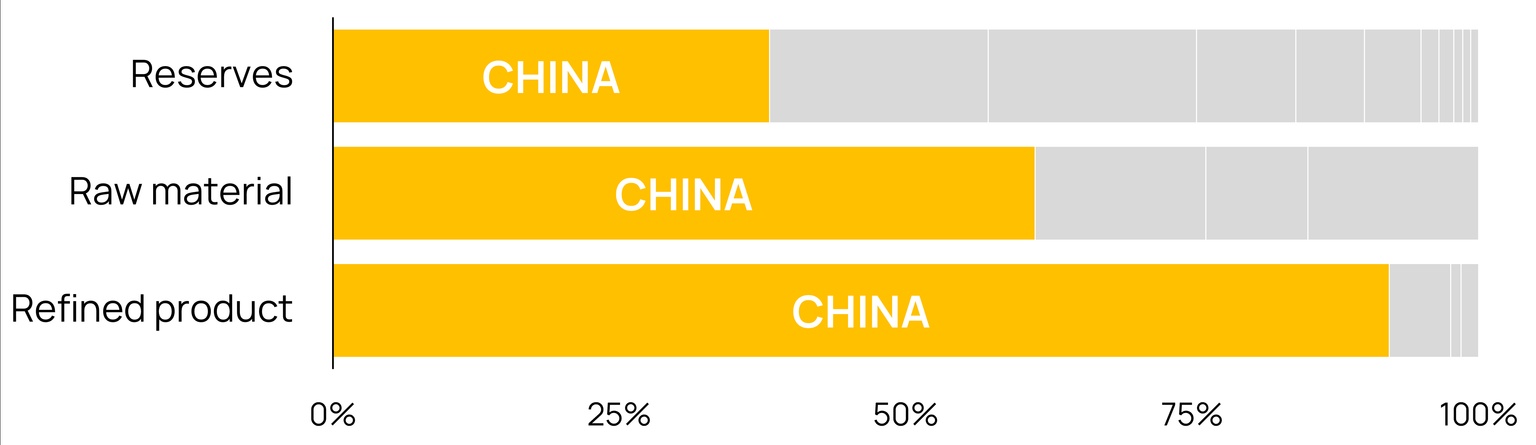

Priorities: China has the largest REE reserves in the world, but its dominance of the supply chain was by no means assured. While other countries focused on digging the ore, China mastered the chemistry: complex extraction and refining of rare earth metals. Since 1975, the Chinese Communist Party has fostered investment in developing advanced processing technologies that are restricted from export.

Source: International Energy Agency

Today, the Asian superpower accounts for just a third of global reserves but 95% of refined rare earth products delivered to the market. And that share is up from 90% just a few years ago, well after the West woke up to the supply issue.

Which is why, when the Trump administration launched its opening salvo of trade tariffs, China leveraged its five decades of strategic policy cornering the critical minerals to turn the screws back on the White House.

The press has not been quite accurate with its framing of China’s actions, often described as an export ban on REEs. There are several ways to restrict exports, including non-automatic licensing, tariffs, quotas and outright bans. This was not a ban, but Beijing said exporters would need to apply for the right to export key rare-earth magnets plus seven minerals: samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium and yttrium.

Why those? Many of the restricted metals are heavy rare earths (HREEs). Prior to 2023, just one HREE refinery existed outside of China, located in Vietnam. But once the lone Vietnamese refinery closed due to tax issues, China found itself with a complete global monopoly over the refined HREE products.

It’s unclear at this point whether Beijing will use the export licenses to restrict the critical minerals from reaching the US, but the initial time and work needed to apply is expected to stall exports in the meantime.

And it nonetheless leaves the US and its western allies — if those are still a thing — in a difficult position. But could the US rapidly develop its own rare earth supply chain in a pinch?

To start with, new mines would need to be developed to produce more of the ore. North America currently has just one operating rare earth mine: MP Materials’ Mountain Pass Mine in California. And while the US does have some reserves, it would be wise to work cooperatively with partners like Australia and India, which have an abundance of the minerals.

And down the supply chain: In its 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy, the Department of Defense set a goal to develop a mine-to-magnet REE supply chain capable of meeting its entire military needs by 2027. That’s looking mighty ambitious.

The DoD has committed over $439 million to the task since 2020, but progress is limited. The Pentagon gave $35 million to MP Materials to support building a heavy rare earth processing facility in 2022. The company’s Texas-based facility, the first of its kind in America, will ramp up production later this year to reach its nameplate capacity of 1,000 tons of neodymium-boron-iron magnets — less than half of one percent what China output last year.

Source: US Geological Survey (USGS)

To support the reshoring, the Inflation Reduction Act contains measures to help develop rare earth supply chains, if the Republicans don’t repeal it. The IRA includes a 10% tax credit for domestic manufacturing critical minerals, including several rare earths, $500 million in funding under the Defense Production Act (DPA) and another $40 million in loan guarantees from the Department of Energy.

The new administration has the right instincts around the need to reduce its dependency on China for rare earth minerals, but it must leverage its allies.

A 2023 strategic report published by the House Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the US and the Chinese Communist Party outlined three pillars to improve America’s strategic position against China: (1) reset trade relations with Beijing, (2) prevent the flow of capital and technology to China and (3) build resilience with American allies.

By working with nations the US has partnered with closely for decades, America can both enhance its exports and reduce its supply chain dependence on the People’s Republic of China, specifically for minerals.

Bottom line: It’s unlikely that a Tom Clancy clandestine mineral extraction plot like securing titanium for the SR-71 Blackbird is on the cards in 2025. And unlike the Blackbird, western nations have already built their advanced technologies and defense capabilities to include critical minerals that have been nearly monopolized by one of its rivals.

In its trade war de-escalation this week, China has said US customers will be able to access rare earth permits more easily, though the situation remains in flux.

The US has found itself in a challenging trade position, but it shouldn’t — and probably can’t — go it alone.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.