Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

Transmission and capacity

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

“The United States’ ability to remain at the forefront of technological innovation depends on a reliable supply of energy and the integrity of our Nation’s electrical grid.”

-White House Executive Order Declaring a National Energy Emergency

Image: Flickr

On Jan. 20, on his first day (back) in the White House, with the unmistakable squeaky slide of a giant sharpie, President Donald Trump signed an order declaring the US is in an energy emergency.

For some, the obvious first question was “what emergency?” The US is the largest producer of natural gas globally, nearly double second place Russia, and its bountiful gas reserves have helped America become the world’s top gas exporter via liquefied natural gas. On the oil side, shale production turbocharged by hydraulic fracturing led the US to be not just the largest oil producer today, but also the largest oil producer of any nation ever in history. With 94 nuclear reactors operating, the US also leads global nuclear power generation, and with four gigawatts of operating capacity, America is number one for geothermal power production, too. The US is the single greatest energy superpower of all time. What kind of emergency can it possibly be facing?

For others though, the question was “what took so long?” After decades of almost zero load growth, the US suddenly finds itself facing a period of rapid new electricity demand from several different fronts, the most important being data centers. Driven by artificial intelligence yet constrained by power supply, data centers received their own executive order just three days later to remove barriers in their development. To not fall behind geopolitical rivals like China, now churning out competitive AI models like they’re Shein jeans but without the same bureaucratic and democratic hurdles, America needs to act. The US is in a state of emergency already, why not declare what we all already know to be true?

The hard truth: For all the bluster and oversized sharpie theatrics, the US is in an energy emergency, though in an area often overlooked by policymakers. While mentioned only in passing in the emergency executive order, America’s looming energy crisis is transmission. More specifically, a lack thereof.

For nearly a decade, the prevailing wisdom has been that building clean energy will solve all our problems. Frances Beinecke, the former president of the Natural Resources Defense Council put it simply: “Wind and other clean, renewable energy will help end our reliance on fossil fuels and combat the severe threat that climate change poses to humans and wildlife alike.”

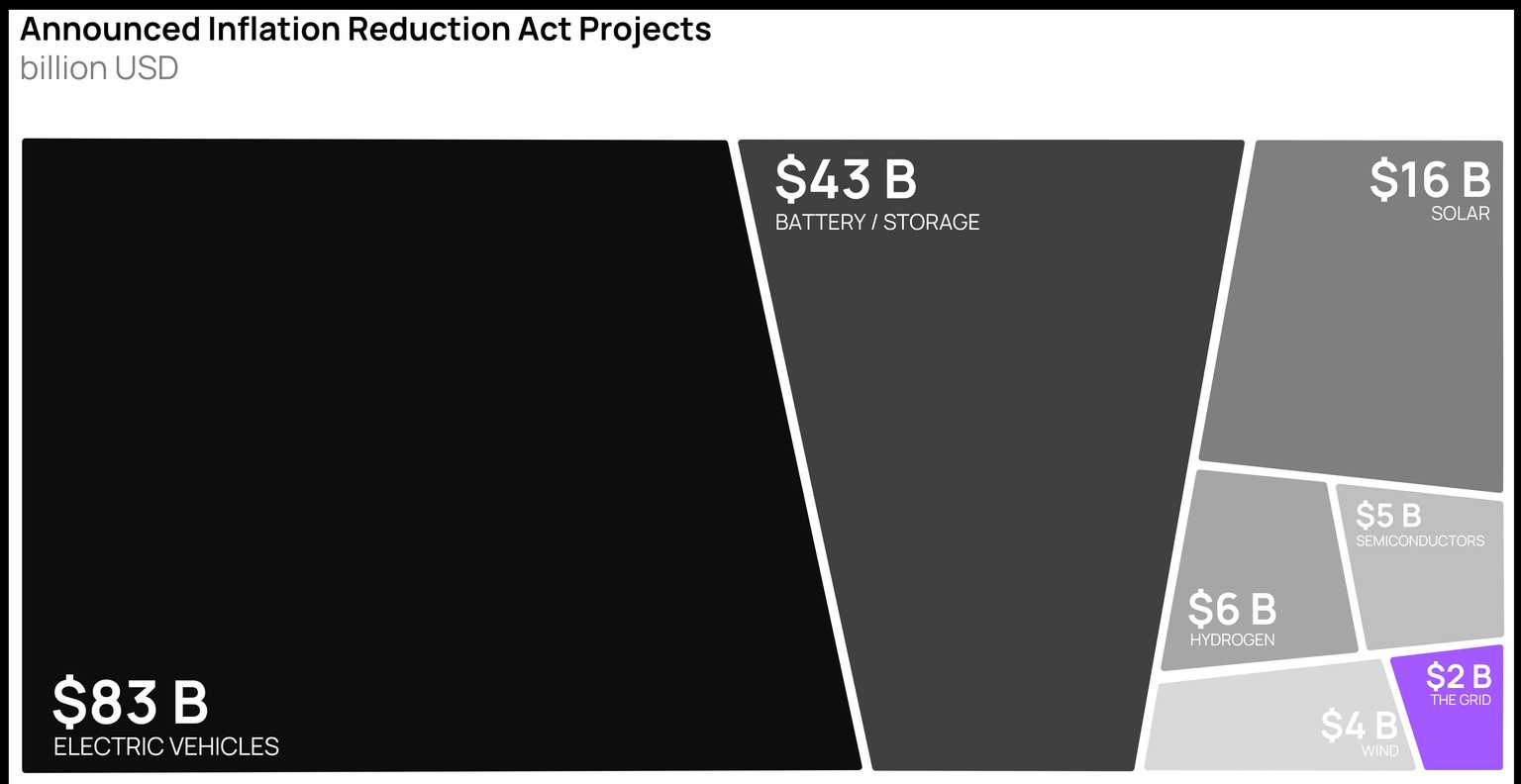

Big, big spending: With that in mind, large energy and infrastructure bills have been passed to catalyze investment into clean energy and power, the most important being the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Since being signed into law in August 2022, $63 billion worth of energy generation and storage projects have been announced under the IRA, supporting new power development.

Source; E2, Post-IRA Project Announcements

But the solutions are not as simple as Frances Beinecke put it. The limiting factor isn’t supply, where almost all the funding has been focused—it’s delivery. And little IRA spending has focused on delivery.

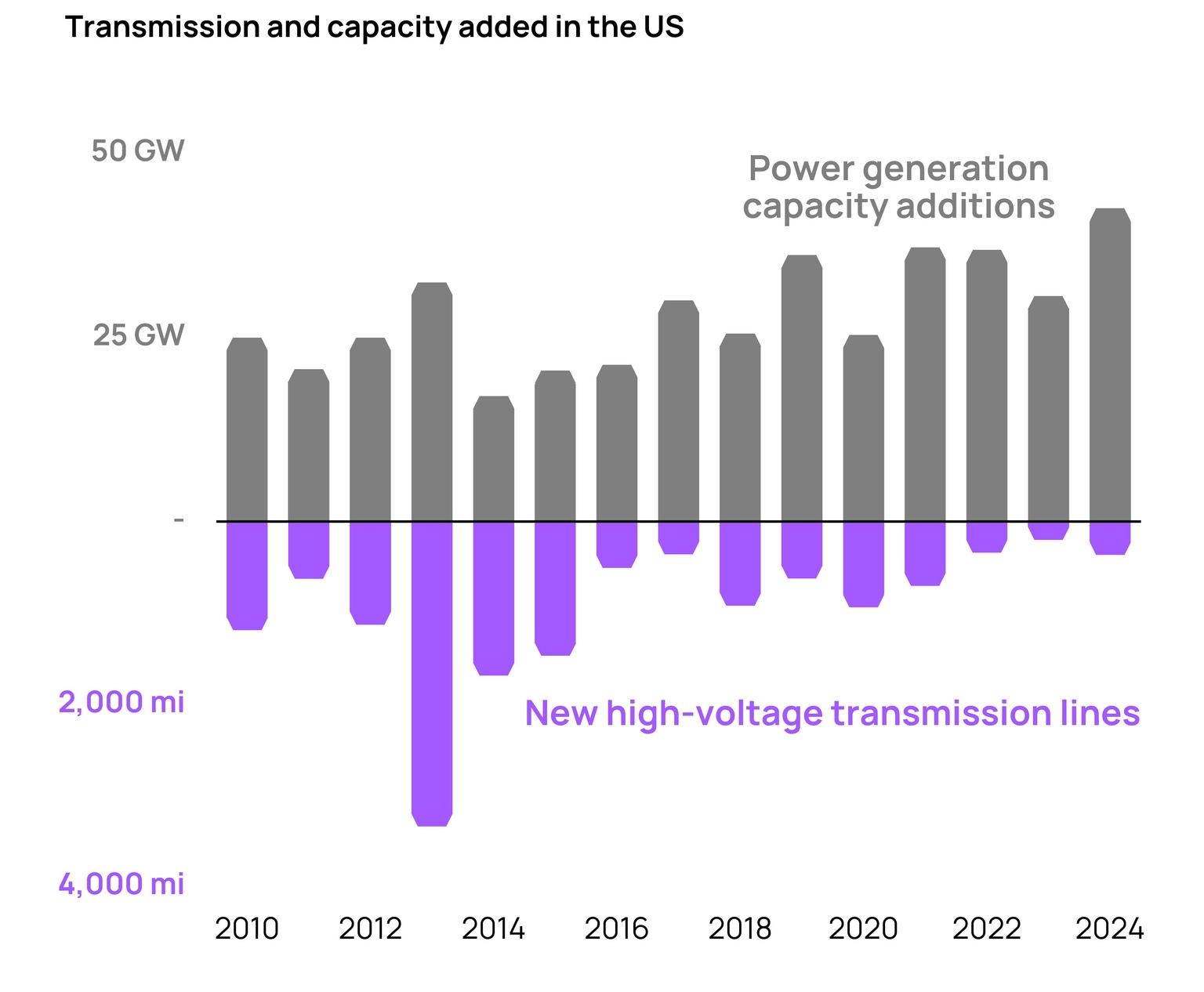

Consider this: The trend for adding new power sources is headed in the completely opposite direction to the means of moving that new generation.

The US built just over 200 miles worth of new high-voltage transmission lines in 2024. While still more than what was built in 2023, totals have been trending down for more than a decade. In 2013, the US built enough high-voltage powerlines to stretch across the continental US, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and then some. Now, a decade on, totals have been reduced to the span of Kentucky. At the same time, more than 40 gigawatts of new generating capacity came online last year, the most added since the early 2000s gas boom.

As a result, many regions are now curtailing power because the grid can’t physically handle it.

Time (mis)management: The misalignment in how long power projects and transmission lines take to build is creating a buildup of projects waiting for approval.

From conception to operation, a new onshore wind farm could be brought online in just over four years with a streamlined process. For a solar farm, it’s closer to two years. Compare that with building a new transmission project today, which is on the order of a decade.

This mismatch in timing has resulted in a logjam of projects waiting for approval to connect to the grid— there are currently 2.6 terawatts of power projects waiting in the interconnection queue. For context, that’s about eight times larger than what was in the queue a decade ago and more than twice the size of the entire US grid currently operating.

Source: Orennia

And while the US struggles to build out new power infrastructure, its great geopolitical rival does the opposite.

China is no slouch: The country spent $166 billion on electricity transmission in 2022, more than the rest of the world combined. The same year, the US spent just $33 billion. Between 2014 and 2021, China planned or completed over 80 times (!) more high-voltage transmissions interconnections than the US. The Asian superpower is investing heavily in transmission.

And the projects China is undertaking are the exact type of projects the US has struggled with. Last year, construction began on the Gansu-Zhejiang Transmission Project, the world’s first ultra-high voltage flexible direct current transmission project, which will bring renewable power from China’s interior out to load centers nearer the coast.

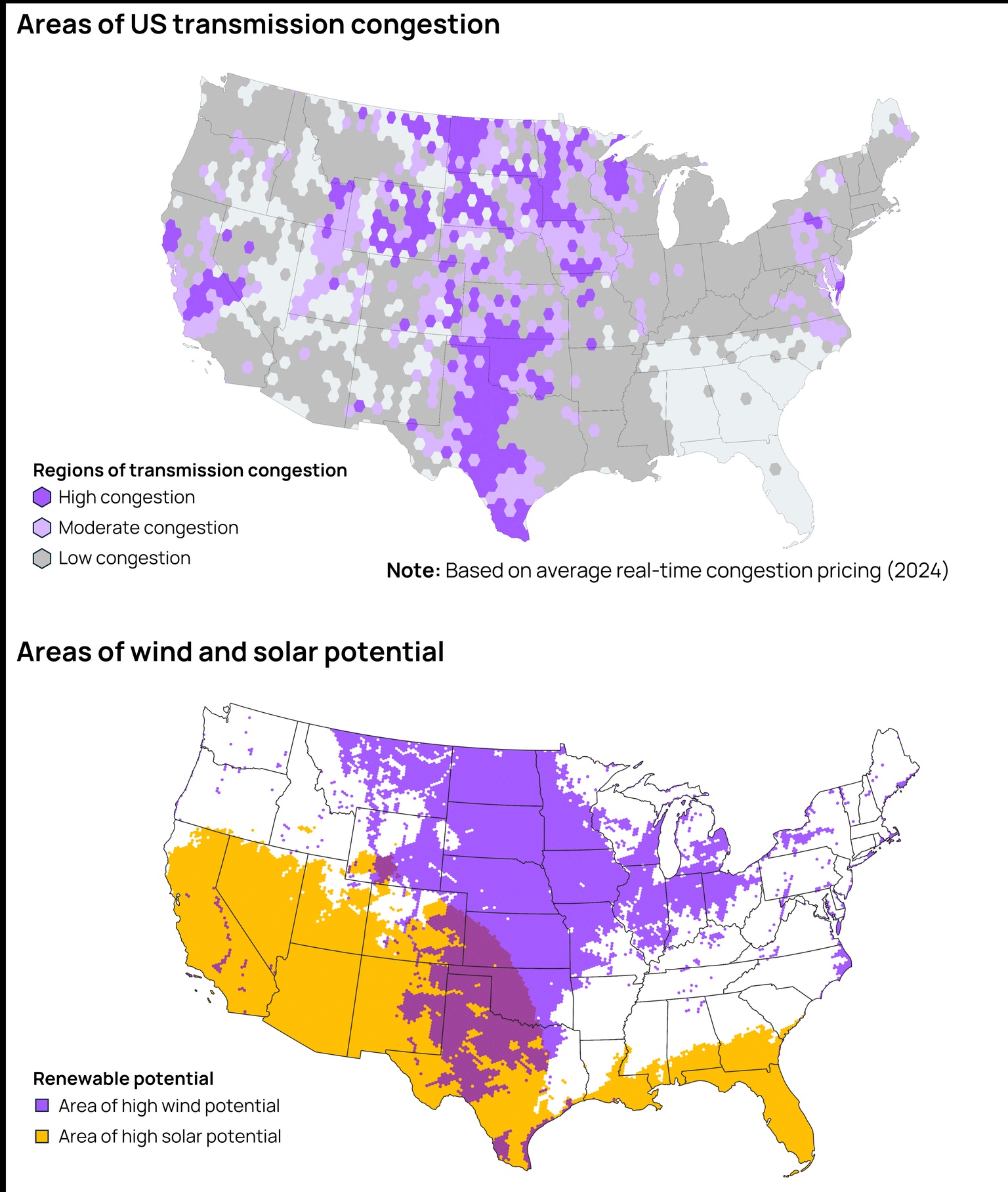

By contrast, it’s in the US Midwest, the heart of American wind power development, where limited transmission is standing in the way of expanding clean energy projects and bringing that power to market.

Source: Orennia

About 15 gigawatts of both wind and utility-scale solar were added in the US in 2020, but their paths have diverged. From 2020 to 2024, the amount of new solar being added to the US grid grew by 150%, while new wind additions fell by 55% in the same period.

Much has been made about supply chains and NIMBYism holding up wind development, but the reality is that many of the key regions where you could place a new economic wind farm would be limited by transmission and face severe curtailment if built. The holdup is often not protestors, but a lack of strung copper.

The process of putting together a transmission project with the appropriate approvals is like stitching together a patchwork quilt made of a kaleidoscope of clashing patches.

Competing interests: The are more than 3,000 electric utility companies in the US, ranging from investor owned to publicly owned and cooperatives. Aligning on where a transmission project will go and who will pay for it is fraught with disagreement. As Grid Strategies founder Rob Gramlich put it, “We don’t have a well-functioning system to determine who benefits and assign costs.”

Add to that the local, state and federal stakeholders who all need to come to an agreement on the project for it to move forward. And the longer the line, the bigger the quilt.

Legal: If navigating the approval process sounds like the Twelve Labors of Heracles, countries often have eminent domain laws that give the government the power to expropriate private lands for public use. More simply, the ability to force through a project.

Unfortunately for grid expansion, eminent domain laws are significantly weaker for transmission projects in the US than for pipelines or highways. States can stifle transmission lines that could connect to the interstate grid.

“The industry grew up as hundreds of utilities serving small geographic areas, the regulatory structure was not set up for lines that cross 10 or more utility service territories,” said Gramlich.

Whether the push for electricity is driven by a need to reduce carbon emissions or to power data centers, all roads lead through improving transmission infrastructure.

Historically, transmission has expanded by about 1% per year. To achieve the power sector goals outlined in the IRA, Princeton University researchers say the expansion rate would need to more than double to about 2.3% per year.

Bottom line: If the newly enacted US Department of Government Efficiency is looking for more a meaningful application of its power than, say, firing and re-hiring hundreds of US nuclear arsenal experts, streamlining the process for new transmission would be a big win. That would be an executive order that everyone would understand.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.