Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

If anyone looks set to take on the renewable status quo, it’s Fervo

Aaron Foyer

Director, Research

You’ve probably heard something along these lines before:

“Renewables may be cheap on paper, but they don’t solve the main challenge of electricity systems: reliability. They’re intermittent and least reliable during extreme weather events, when they’re needed most. Reliable power systems need coal, gas or nuclear, not renewables.”

You’ll have no difficulty finding similar hot takes on LinkedIn, especially if the latest episode of Landman just dropped. But here’s former president Joe Biden on grid reliability:

“We’re going to need natural gas and nuclear as we transition to a clean energy economy,” said the 46th president, an ardent supporter of renewables.

The notion that renewables aren’t reliable seems to ring true because of the intermittency of wind and solar, and what’s historically been considered baseload. But a new generation of geothermal producers looks poised to challenge that view.

Fervo, a Houston-based geothermal company that just came off a huge Series E in December, has quietly filed for its IPO and is getting ready to turn on its flagship power project later this year. If anyone looks set to take on the renewable status quo, it’s Fervo.

So, will this clean power startup with oil and gas roots change the electricity landscape? Let’s drill down and find out.

Tim Latimer, Fervo’s chief executive and co-founder, comes across less like a climate evangelist and more like a shale veteran repurposing old tools for a new resource.

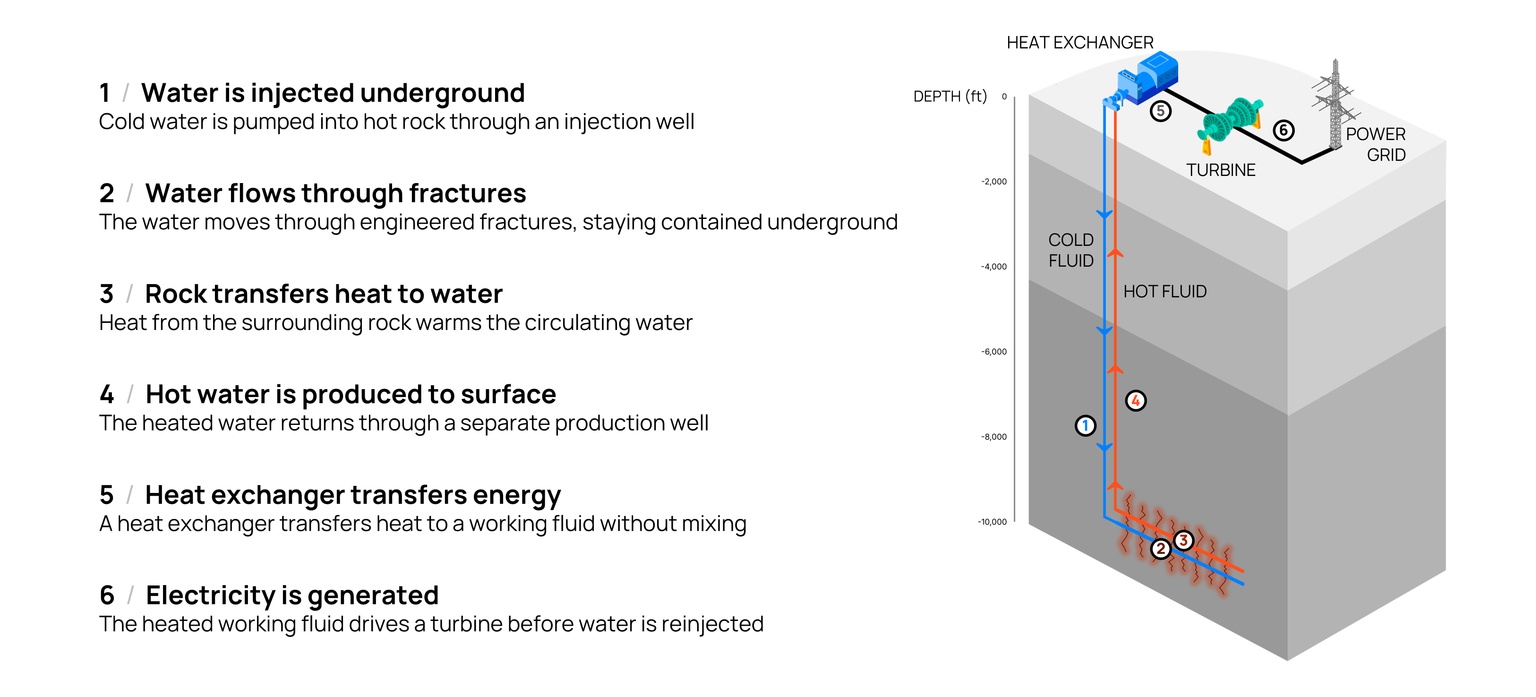

The problem the geothermal industry has faced forever is a lack of good reservoirs. There are few places on Earth with the perfect combination of hot water and shallow permeable rock where the entire system works economically. Where they do exist, they’re amazing, but they are rare.

Latimer and his co-founder, geologist Jack Norbeck, wondered whether they could borrow the oil and gas industry’s approach of manufacturing artificial reservoirs to crack open the geothermal fairway. This would be right at home for Latimer, a former BHP drilling and completions engineer.

Maturing: In just six years, Fervo has gone from an R&D-focused startup to near commercial power provider.

Following its initial raise in 2019, the company went on to complete its first field demonstration in 2023, dubbed Project Red located in Nevada. This marked the world’s first geothermal system to use horizontal wells for heat extraction. Later that year, the 3.5-megawatt plant was fully operational and supplying power directly to Nevada’s utility, NV Energy.

Building on the success of Project Red, Fervo is developing a full-scale 115-megawatt project in Nevada called Corsac Station, using a first-of-its-kind Clean Energy Tariff. NV Energy will buy electricity from Fervo and sell it to Google at a set rate, with the project expected online later this decade.

But all eyes are on southwest Utah and Fervo’s Cape Station project, which aims to be the largest next-generation geothermal facility in the world. The first 100-megawatt phase is expected to be online in October and would make the project the first commercial-scale EGS plant in the world bringing clean firm power to the grid.

Source: Orennia, public disclosures

Raising the heat: Fervo’s funding history reads less like a typical clean energy startup and more like a crossover infrastructure play.

The company’s Series A took place in 2019, raising $11 million through a group of investors that included Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the Bill Gates-based climate tech venture fund. Since then, Fervo has added the who’s who of mainstream clean energy funds to its cap table, including BEV, Congruent Ventures and even Google.

But with links to the oil and gas industry, Latimer and Norbeck have also welcomed investments from major energy firms such as Devon Energy, BP Ventures and Liberty Energy. The latter is notable as Liberty’s $10 million investment was made when Chris Wright, now the US Secretary of Energy and long-time geothermal advocate, was CEO of the shale producer.

The company’s latest financing, a $462 million Series E funding round that closed in December, brought the total amount raised to $1.5 billion, according to the company. And Axios reported last week that Fervo has quietly filed for its IPO and could go public later this year.

It’s rare to find a well-funded technology that both the left and the right, Democrats and Republicans, can get behind, so the hype and excitement around Latimer, Norbeck and Fervo is pronounced. But success is far from guaranteed.

More to it than just being hot: There’s no doubt that making geothermal cheap and economic will be hard. Sure, they’re using technology perfected by the oil and gas industry, but the energy being harvested by the two industries is very different. A barrel of oil contains about 120 times more useful energy than a barrel of hot geothermal water converted into electricity.

Fervo’s system also uses a lot of its own energy in the process. The EIA shows the first three generators at Cape Station have a combined nameplate capacity of 159 megawatts, but only 91 megawatts of net capacity. In plain English, that means the system is expected to use 40% of the electricity it generates just to operate.

If Fervo fails to meet lofty expectations, it will become just the latest next-generation geothermal to do so. The graveyard of companies that have tried and failed to launch a modern geothermal industry include Raser Technologies, Potter Drilling and Geodynamics.

And it’s tempting to explain away those failures because of their vintage. But Canadian startup Eavor, which uses a closed-loop system, just brought its own flagship geothermal project online in Germany and early reports about its performance are disappointing, to put it lightly.

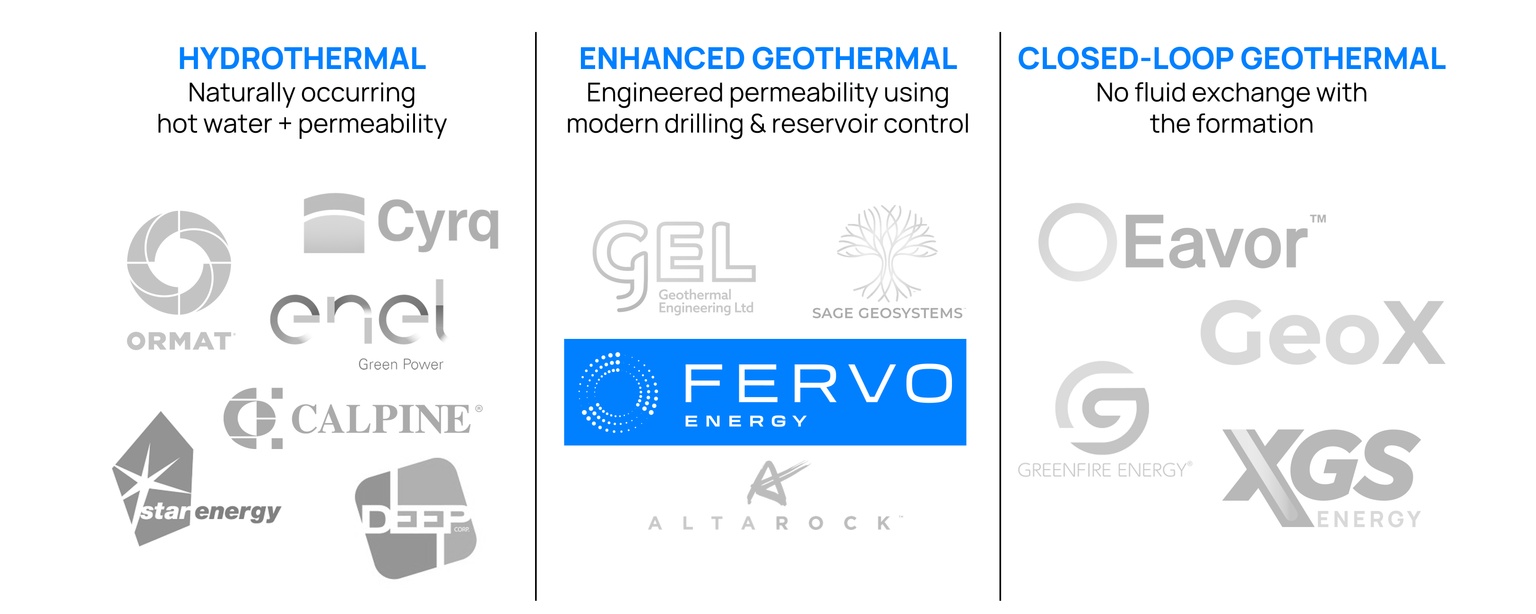

Same heat, different engineering: To be fair to Eavor, it’s too early to call its project in Germany a failure: it has just one month of operating data and it takes time to learn how to drive these power plants. Its closed-loop design likely requires less pumping, so it consumes less of its own generated power, and might be more universally deployable. But its approach to geothermal is notably different from Fervo’s.

Eavor circulates fluid through a pair of deep pipes that are connected underground at the tips, like one really long snake, collecting heat via heat transfer through the pipe walls. Fervo also uses a pair of deep wells, but it moves the fluid between injecting and producing wells through a massive fracture network created by a hydraulic fracturing that allows the water to touch much more rock. Surface area matters here, and the difference between Eavor and Fervo is akin to holding a glass of ice water and doing the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. That will translate to more electricity for Fervo’s design.

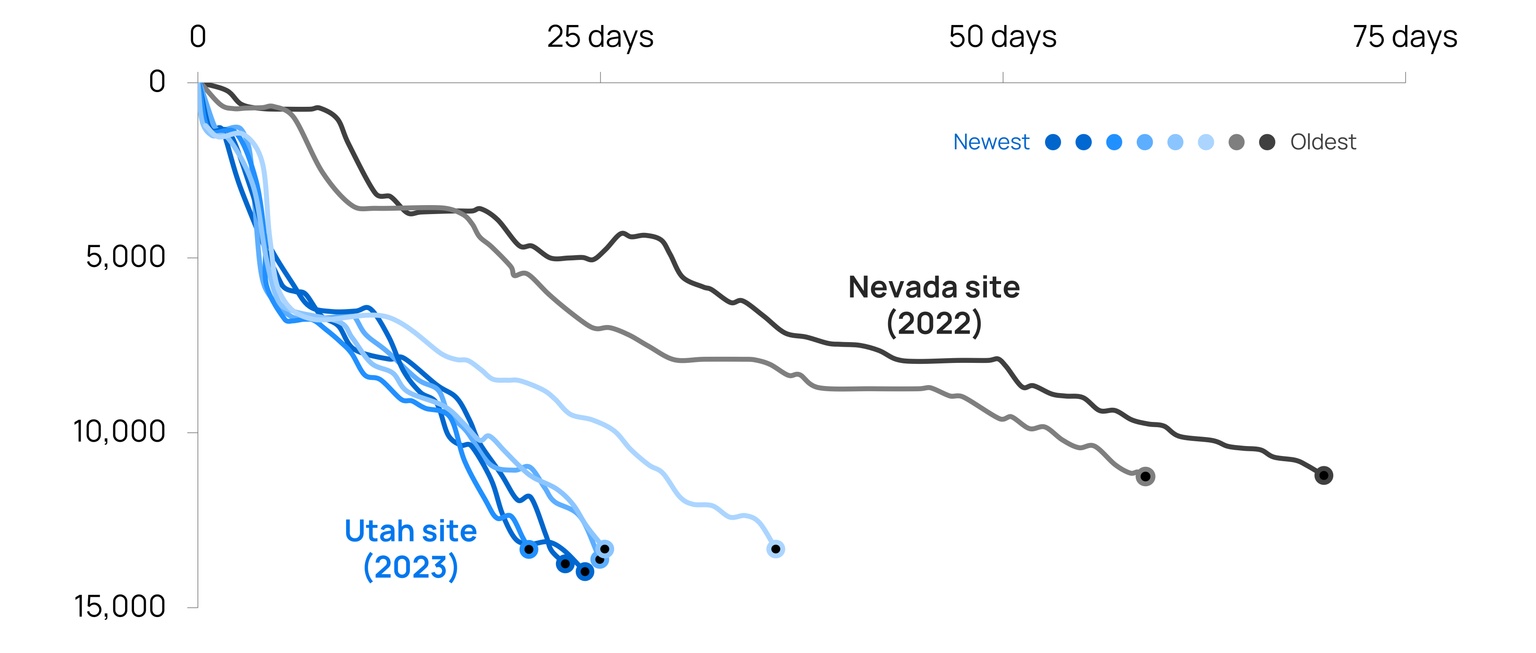

There is also precedent from the shale industry to the improvements that can be achieved in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. A single rig in the Permian today can bring on 15 times more new daily oil production than a rig could a decade ago in the same field.

In just two projects, Fervo has shown it has the same capacity for improvement. The difference between drilling the Project Red pilot project in Nevada and Cape Station commercial project in Utah is stark. In 2022, it took 70 days to drill 11,200 feet in a well at the pilot project in Nevada. Just a year later in Utah, it took just 24 days to drill a well nearly 14,000 feet.

Akindipe, Witter, et al. (Stanford University)

If Fervo’s first commercial project in Utah comes on later this year and shows promise, the industry has a bright future ahead.

Holy Grails are always cliché, and it’s cringey to hear anything thrown around as the Holy Grail of energy. But underground heat is truly everywhere, so there is a cost structure you eventually hit with geothermal where the technology goes from nifty to world changing.

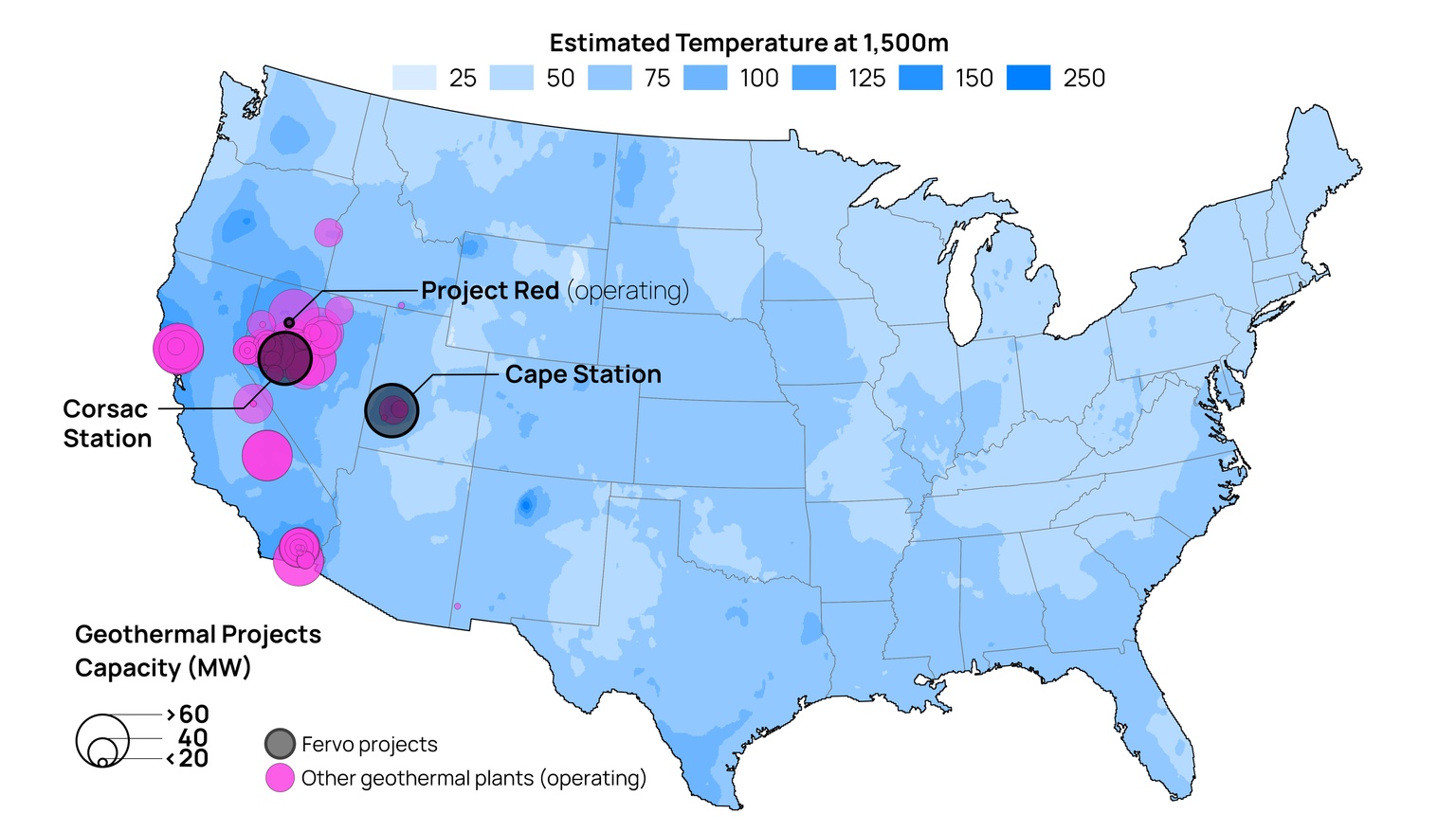

Earlier this year, the National Laboratory of the Rockies (formerly the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) put out a map of the US highlighting areas suitable for enhanced geothermal systems like Fervo’s. The punchline is that nearly everywhere west of Nebraska shows a lot of potential.

Fervo is among a small handful of cleantech companies where the excitement around the opportunity is palpable. Can it go from flashy R&D startup to a commercial clean power provider challenging the notion renewables don’t contribute to reliability? We’ll get a pretty good sense of that later this year when the company brings Cape Station online.

As baseball legend Yogi Berra put it: “In theory, there’s no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” In 2026, we’ll finally get to see what Fervo’s technology is capable of.

Data-driven insights delivered to your inbox.